The Rise of Rural Rhythm

The Hayloft Gang: The Story of the National Barn Dance

By Paul L. Tyler. University of Illinois

Press, 2008, pp 19-71.

With audio annotations. Part 2, pp. 37-71

Go to Part 1, pp. 19-37

The Rural Rhythm of the Hayloft Gang

The actual sounds of the National Barn Dance before World War II are quite elusive, for the words and pictures of the WLS Family Albums carry no audible signal. For readers able to render music notation into a musical performance, there are several dozen song folios published by NBD artists before 1942 that contain lyrics, piano arrangements, guitar chord symbols, and, in one case, numbers and symbols indicating where and when to draw or blow on a ten-hole harmonica. Songbooks like these would have been helpful for playing along at home with an artist heard regularly over the airwaves. But today, separated by many decades, such published arrangements are by themselves insufficiently descriptive to enable an accurate re-enactment of the music of the Old Hayloft. 36

A few examples will disclose some of the challenges encountered. When compared to their phonograph records, the song folios published for Bradley Kincaid, Mac & Bob, and others contain quite accurate transcriptions of the lyrics of the songs. Other artists' songbooks show more lyrical variation, but the differences are still relatively minor. More crucial are the differences in form that can be found by comparing printed scores and recorded versions of the songs. For instance, the songbook version of the Arkansas Woodchopper's "The Bronc That Wouldn't Bust" gives no indication that the fourth and final stanza was used by Arkie as a refrain after each of the other three stanzas on the recorded performance. In addition, for this song and another cowboy song, "I Am a Texas Cowboy," the songbook supplies yodels that are less elaborate and only half the length of what is heard on Arkie's phonograph records. 37

Angel of East Tennessee by Karl & Harty, 1941

Down By the Riverside by Mac & Bob, 1926

The most glaring inaccuracies in the song folios are found in the musical notations themselves. Vocal harmonies are entirely missing in the folios published for Mac & Bob and Karl & Harty, duets whose characteristic styles were built on close harmony. Examples of melodic imprecision can be found time and again in the songbooks. It is admittedly difficult to clearly and cleanly transcribe the vocal nuances of a traditional folk singer who employs slides, scoops, and other vocal ornaments in moving from note to note. (Such features epitomized the emerging distinctiveness of country music, including the styles heard on WLS, and were often contrary to the strictures and conventions of formal music training in the first half of the twentieth century.) Still, the published song folios often miss basic melodic steps and turns of the performance practices heard on records made by NBD artists. 38

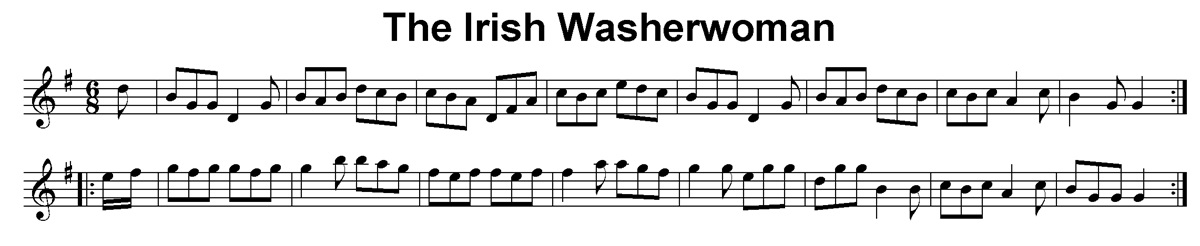

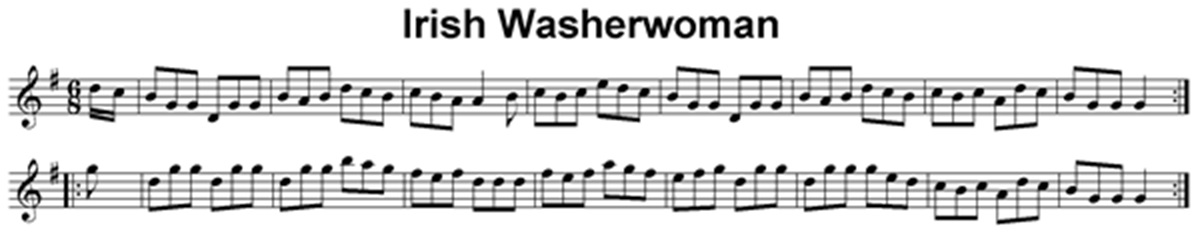

A telling instance is found in the notation for the fiddle tune, "The Irish Washerwoman," credited to Tommy Dandurand. The version printed in a landmark 1935 anthology (see Figure 15) is nearly identical to other published settings of this standard piece. My transcription of an actual Dandurand performance–recorded in the Gennett studios in Chicago in August of 1927–shows some notable differences that reflect Dandurand's personal shaping of the tune (see Figure 16). In the first strain he preferred a gently curving melodic contour over the repeated jumps of the conventional setting. His second strain comprised a melodic idiosyncracy in the first half, and a distinctive rhythmic shift in the descending figure leading to the final notes. And finally, Dandurand's record featured square dance calls sung by Ed Goodreau, in what is likely the earliest recorded example of a "singing call," a style of calling that would come to rival the older style of chanted and rhymed calls known as "patter." 39

Irish Washerwoman by Tom Owen's Barn Dance Trio, 1926

Discs made for the record industry provide the best opportunity available today to hear something resembling the sounds of the early National Barn Dance. Still, it must be remembered that such recordings do not represent performances in front of a radio microphone, but rather in the studio of a rival business concern. During the 1920s and '30s, record companies' profits dipped sharply, due in large part to the formidable competition afforded by radio. Bill Malone, for one, has argued that commercial country music developed out of the kinds of rural folk music the record companies turned to in order to develop new markets and reverse their slumping sales. Sears, on the other hand, saw an opportunity to work both sides of the aisle and entered into a complicated agreement with the Gennett label–affiliated with the Starr Piano Company of Richmond, Indiana–to produce budget records featuring Barn Dance artists on the Challenge and Silvertone labels. In later stages of the five-year deal, the WLS material recorded by Gennett was issued on Supertone and Conqueror. 40

By the start of 1928, four Barn Dance acts–Walter Petersen, the Kentucky Wonderbean, Tom Owen's Barn Dance Trio, Tommy Dandurand & His Gang of WLS, and Chubby Parker–had recorded at Gennett's studios in Richmond and Chicago. Sears sold these records through its ubiquitous catalog. Weekly appearances on one of the most popular shows on radio undoubtedly provided the kind of publicity that other rural recording artists envied. Even after Sears sold WLS to the Prairie Farmer, Barn Dance artists Bradley Kincaid, the Arkansas Woodchopper, and Pie Plant Pete continued to record at Gennett for labels featured in the Sears catalog.

Red Wing/My Little Girl/Turkey in the Straw by Kentucky Wonderbean [Walter Petersen], 1924

The commercial alliance between Sears, WLS, and a record company reached a most interesting, and perhaps most profit 41able, convergence in 1931, when Sears hired Gene Autry to broadcast regularly on Conqueror Record Time, a show sponsored by the retailer on WLS. Because of his growing popularity, Autry had just been signed to a contract by the ARC group of record labels, which then included Sears's own Conqueror label. For its part, Sears loaded its catalog with Gene Autry merchandise, including a signature-model guitar, song books, and a section of Autry records on Conqueror. Topping it off was the fact that Autry became a regular guest on the National Barn Dance. The irony is that Autry, who became perhaps the most famous and successful performer associated with the Barn Dance, was not an employee of WLS, but of Sears! 42

Here, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is difficult to fathom the earlier rivalry between the phonograph and broadcasting industries. Nevertheless, at some stations–most notably, WLW in Cincinnati–broadcast performers were prohibited from making records. Other professional country musicians who worked in radio never bothered to record, because the financial returns were minimal. Conversely, many of the rural string bands and songsters, who were the first wave of country music on record, never really became professional entertainers. To have a career in country music in the 1930s, it was virtually an absolute necessity to get a good foothold in the broadcast industry, and most radio jobs for country musicians were non-paying. Regular radio air time allowed a barnstorming act to publicize its public appearances in the station's listening area. It was through admissions and the sales of souvenir photographs and songbooks that a band of young country musicians could make a living. 43

For several reasons, the National Barn Dance proved to be the pinnacle of the country music field before World War II. Perhaps most importantly, broadcasting on WLS was a paying gig. George Biggar claimed the average WLS staff musician's weekly salary was $60; those who appeared only on the Barn Dance got union scale or about $20. As Patsy Montana would disclose, however, WLS was not willing to pay female artists the same scale. Only when she relied on the bargaining power of a recent hit record and threatened to quit did WLS executives agree to a $60 salary, half again the size of their original offer. 44 Furthermore, because Chicago was an important center of recording for major labels (Columbia and Victor), the independents (Paramount, Gennett, and ARC), and the new budget labels (Bluebird and Decca), NBD artists had enhanced opportunities to make records.

And record, they did! Through a concerted effort over the last few years, I have been able to listen to nearly seven hundred sides–out of the 2,333 referred to earlier–recorded by Old Hayloft artists. 45 I have heard at least one recording by nearly two-thirds of the fifty-five NBD country artists who also made records between 1924 and 1942. The musical examples assembled comprise one to three CDs worth of material (from twenty to seventy pieces) for each of the following major NBD artists: Arkansas Woodchopper, Gene Autry, Girls of the Golden West, Hoosier Hot Shots, Karl & Harty & the Cumberland Ridge Runners, Bradley Kincaid, Lulu Belle & Scottie, Mac & Bob, Louise Massey & the Westerners, Clayton McMichen & the Georgia Wildcats, Patsy Montana, Little Chubby Parker, and the Prairie Ramblers. At the other end of the scale, I have sampled only a few songs by artists like the Happy Valley Family, Lonnie Glosson, Jo & Alma (the Kentucky Girls), Fred Kirby, Pie Plant Pete, Blaine & Cal Smith (the Boys from Virginia), and the Smoky Mountain Sacred Singers (a quartet that included Mac & Bob). Some NBD artists who made records are still aural mysteries to me: Dixie Mason, the Flannery Sisters, the Dean Brothers, Sally Foster, the Hill Toppers, the Maple City Four, Tom & Don, and Romaine Lowdermilk.

The Old Woman and the Crow by Gene Autry, 1931

Plant Sweet Flowers on My Grave by Jo & Alma, 1938

Two discographical reference works have been published recently that provide complementary tools for assessing the repertories of early country music artists, including these performers from the Old Hayloft. Russell's Country Music Records, already introduced, provides chronological lists of each artist's recorded masters, grouped by session. Guthrie Meade's posthumously published Country Music Sources: A Biblio-Discography of Commercially Recorded Traditional Music, contrarily, is organized by song, which Meade painstakingly sorted into a taxonomy of song families and types. Meade's magnum opus does not include every country song recorded before 1942–as does, at least in theory, Russell's–only those that he deemed traditional according to the following criteria: "those recorded songs that have appeared in published folk song collections, as well as those songs copyrighted or appearing in print prior to 1920." Meade estimated that the entirety of recorded country music was 20,000 masters. Further, he claimed that his definition of a traditional song covered "around 90% of the recorded repertoires of the early country entertainers, but less that 50% of later performers." The majority of the Barn Dance artists listed in the previous paragraph belong to the latter category. 46

In what follows, I will briefly summarize the biographies and recorded repertories of the early Barn Dance's most important rural musicians and will further attempt to draw stylistic connections to other members of the Hayloft Gang by grouping the artists in rough chronological order in these categories: fiddlers, folk song artists, modern folk song artists, western song artists, and novelty musicians. These categories are for convenience and are by no means to be regarded as mutually exclusive. The repertories of many NBD performers contained material that belongs in more than one category. Nevertheless, my hope is that this scheme will help reveal the both the breadth and depth of rural rhythm heard in the Old Hayloft.

Fiddlers

In 1935, both George Biggar and John Lair published nostalgic remembrances of the beginning of the National Barn Dance, and both identified Tommy Dandurand as the show's first old-time fiddler, or as leader of the first fiddle band. However, there is no evidence to verify this claim. The second week the Barn Dance was on the air, one Chicago newspaper listed the scheduled performers as follows: "Evening barn dance; special music by old-time fiddlers; features by Timothy Cornrow, violinist; Kentucky Wonderbean, harp; Cowbell Pete, bells." It is possible that Dandurand may have been the leader of that anonymous band of fiddlers, or the real person behind the pseudonym Timothy Cornrow (another paper reported that Cornrow was "from Ioway"). Yet, through the first half-year of the NBD, twenty other fiddlers' names are listed in the Chicago papers as making an appearance. The name "Fiddling Tommy Danduran" [sic] does not appear until January 3, 1925. Ironically, that was an evening when Dandurand was back home in Kankakee competing in a fiddle contest. 47

Throughout that first summer of 1924, the National Barn Dance was devoted to an on-air fiddle contest. Contestants were nominated by their local communities and were named each week in the Chicago Evening Post and Literary Review: e.g., C.A Pemwright of Mt. Ayr, Indiana; N.G. Aldrett of Morrison, Illinois; Chester Crandill of Hebron, Wisconsin; W. Goatschel of Oak Park, Illinois; Thomas Frill of Mason, Illinois; and unnamed fiddlers from the Iowa Farmers Union. The contest was for teams that were to include a lead fiddler, a second fiddler, and a "caller who knows what real calling means." Not all entrants met these criteria, and even the winning team from Kenosha, Wisconsin included only on George Adamson on fiddle and George Murdick on piano. 48

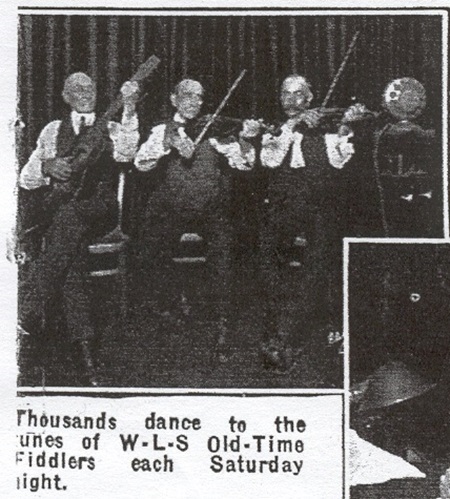

In February of 1926, the NBD's resident square dance caller, Tom Owen, a native of Missouri, recorded eight fiddle tunes with calls at the Gennett studios in Richmond, Indiana. In the absence of any concrete data, most historians have attributed the fiddling on those discs, once again, to Tommy Dandurand. But a comparison of a transcription of the "Irish Washerwoman" recorded at that session (Figure 17) with Dandurand's recording of a year later (Figure 16), suggests that these are performances by two different fiddlers. (Further comparisons of other tunes common to both session provide additional support for this conclusion.) The identity of the fiddler in Owen's Barn Dance Trio will probably never be known. A small likelihood exists that it is one of two fiddlers in a photograph printed several times in early promotions of the Barn Dance: Illinois fiddlers Frank Hart of Aurora and William McCormack of Marseilles are pictured along with guitarist James E. Priest (Figure 18). 49

Tommy Dandurand–born in 1865 in Kankakee County, Illinois, third generation of a pioneer French family that settled in "Le Petit Canada" in Bourbonnais Township–did appear regularly on the Barn Dance from the fall of 1924 through at least 1930. 50 In 1927, he made two trips to the Gennett studios in Chicago and recorded fourteen sides, thirteen of which had square dance calls. The remaining side was a medley of waltzes. These performances by Tommy Dandurand & his Barn Dance Gang were in accord with the stated rules of the 1924 fiddle contest on WLS: Dandurand and Rube Tronson, a native of Wisconsin, fiddled in a rarely recorded, archaic, regional style in which the lead fiddler plays the melody along with chordal accompaniment from a second fiddler. The caller on these sides was Ed Goodreau, also from Kankakee. On a few pieces in 6/8, or jig, time, a banjo can be faintly heard.

McLeod's Reel by Tom

Owens Barn Dance Trio, 1926

Leather

Breeches by Tommy Dandurand, 1927

Barn

Dance, Pt. 1 by the National Barn Dance Orchestra,

1933

Fishing

Time by the National Barn Dance Orchestra,

1933

Knickerbocker

Reel by the Rustic Revelers, 1934

Sunshine

Special by the Rustic Revelers, 1934

Figure 18: James B. Priest, Frank Hart, & William McCormack. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum.

Since Guthrie Meade included all of the tunes recorded by the Owen

and Dandurand band in his Country Music Sources, they are

traditional according to his definition. The same can be said for

eleven of the twelve fiddle tunes, with calls, recorded in 1933 in

Chicago for Bluebird by the National Barn Dance Orchestra.

None of the musicians–two fiddles, two guitars, and a mandola–have

been identified, and in truth, only the band name connects these

recordings to the WLS show. The mandola was not all that common an

instrument, however, and a mandola player, Chick Hurt of the Prairie

Ramblers, had just joined the Barn Dance that year. A picture of

Rube Tronson's Texas Cowboys printed in the 1933 WLS Family

Album provides another tantalizing hint. It shows two

fiddlers, both natives of Wisconsin: Tronson, the orchestra leader,

and Leizime Brusoe, from Rhinelander. 51

Another puzzling fiddle band, with possible ties to WLS, recorded in

Chicago in 1934, when the Rustic Revelers cut eight sides

for Decca (five of which were classified as traditional by Meade).

The only possible connection, the name of the band, is in this case

quite a bit more tenuous. Still, the Hoosier Hot Shots, an immensely

popular novelty band that joined WLS in 1933, were the direct

offspring of a barnstorming comic group known as Ezra Buzzington's

Rustic Revelers. Fiddler Buddy McDowell, a native of Van Wert, Ohio,

who later joined the NBD in a reconfigured lineup of the Cumberland

Ridge Runners, was another Buzzington alumnus. Was McDowell the

fiddler in the Rustic Revelers 1934 session? Could Tronson and

Brusoe have led an actual National Barn Dance Orchestra through its

paces in that 1933 Bluebird session? I doubt we will ever know for

sure.

Good

for the Tongue by Leizime Brusoe, 1937

(With this tune he won the Chicago Herald & Examiner

Fiddle Championship in 1926.)

Grey Eagle by Slim Miller (Pinex Merrymakers), 1938

Callahan by Lily May Ledford (Pinex Merrymakers), 1938

From the mysterious Timothy Cornrow, to the unnamed fiddlers of the National Barn Dance Orchestra, most of the Old Hayloft's fiddlers toiled in anonymity. Though they were the sparks that originally ignited the National Barn Dance, they were clearly never the stars. There were a few exceptions, such as Lily May Ledford, a nineteen-year-old fiddler, banjo-picker, and traditional folksong artist from Lombard, Kentucky, who appeared on the Barn Dance in 1936 before heading off to Cincinnati with John Lair the next year to form the celebrated Coon Creek Girls. Homer "Slim" Miller was a baggy pants comedian and versatile fiddler for the Cumberland Ridge Runners. Upon hearing preserved transcriptions of the Pinex Merrymakers, it is evident that Miller was equally adept with old-time square dance tunes and more modern styles of fiddling, influenced by jazz and swing. Slim only recorded two fiddle tunes on commercial discs: "Roundin' Up the Yearlings," which Meade classified as traditional, and his signature piece "Goofus," which was too recent a composition for inclusion in Meade.

Another fiddler in the same mode came to the Barn Dance in 1933. Clayton McMichen had recently quit one of the most commercially successful rural string bands in the United States, Gid Tanner & his Skillet Lickers, who recorded over a hundred sides for Columbia between 1926 and '31. McMichen, however, had grown weary of straight ahead, old-time fiddling and was "determined to forge a new string band music that borrowed heavily from Big-Band Swing." Over the next few years, he would make strides toward that goal with his new band, the Georgia Wildcats, which featured a young, jazz-adept guitarist and fellow Georgian, Slim Bryant. 52 But based on the thirty-four pieces the Wildcats recorded in the two years before they came to Chicago, they were still firmly grounded in traditional old-time music. The path McMichen would follow toward the hot sounds of jazz and swing are prefigured in a couple of these recordings: e.g., "Wild Cat Rag"; "Yum Yum Blues" (a Slim Bryant composition); and a western song composed by two Chicagoans, "When the Bloom Is on the Sage,"

McMichen's vision was partly shared by several other National Barn Dance fiddlers: Tex Atchison and Alan Crockett, early and later fiddlers with the Prairie Ramblers, and Curt Massey of the Westerners. (All three will be introduced more fully in the treatments of their bands in following sections.) The blending of old-time fiddling with the hot licks of jazz and swing was achieved soonest, perhaps, by the Prairie Ramblers, with Atchison leading the way. Nevertheless, Massey, Atchison, and Crockett could fiddle an old-time breakdown with the best. Massey's 1934 "Brown Skin Gal Down the Road," and Atchison's 1937 "Raise the Roof in Georgia" and "Kansas City Rag"–with dance calls–would be driving enough for any floor filled with square dance sets.

Lightfoot Bill by Alan Crockett (with Arkansas Woodchopper), 1941

In 1941, as a nationwide square dance revival was gathering steam, Alan Crockett went into the studio with the Arkansas Woodchopper's Square Dance Band to record tunes and calls for seven square figures and an old-time "circle two-step." Crockett played "Walking Up Town" for the latter, a variant of a widespread tune commonly known as "Twinkle Little Star" (not the same as the children's song). Meade identified all eight of the tunes fiddled by Crockett as traditional.

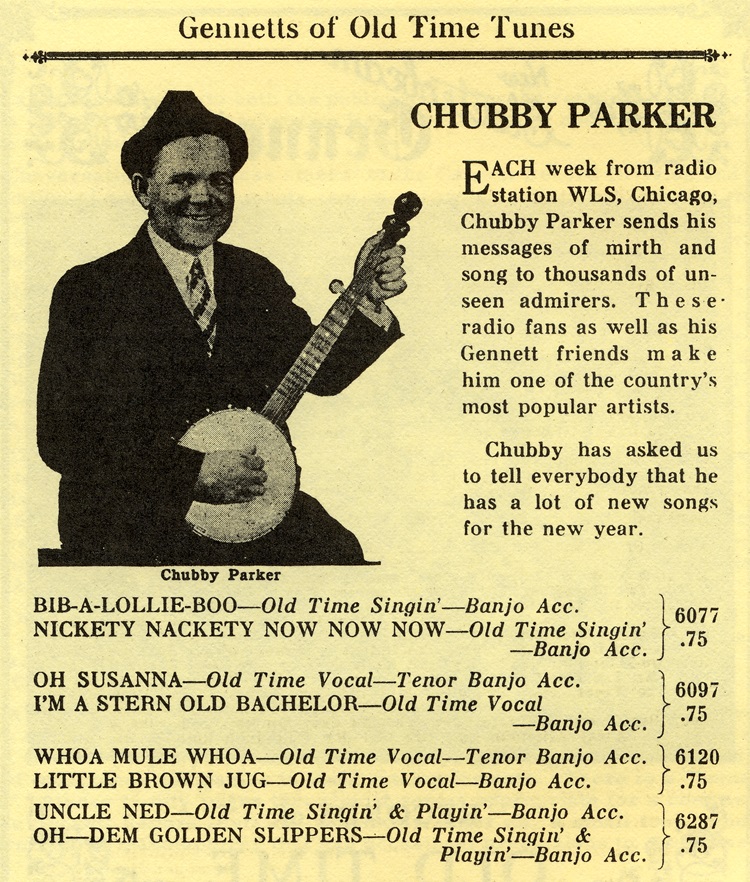

Folk Song Artists

Little Chubby Parker–his given name was Frederick–was perhaps the National Barn Dance's first true folksinger. Nearly a decade after he left the program, John Lair described him as "the first to bring to radio the home songs of America." 53 His name first appeared in program listings for the Barn Dance on July 18, 1925, but disappeared sometime in 1927. Between 1927 and 1930, he recorded thirty-six sides for Gennett (and Sears), and he recorded nineteen more for Sears' Conqueror label in 1931. Parker also recorded two sides for Columbia in New York in 1928. One of these, "King Kong Kitchie Kitchie Ki-Me-O," a version of a satirical English ballad commonly known as "Froggie Went a-Courting," was included in the influential Anthology of American Folksong, issued in 1952, and was the first introduction of an early National Barn Dance artist to most postwar folk music revivalists.

Nickity Nackety Now Now Now by Chubby Parker, 1927

In Kansas by Chubby Parker, 1931

Beyond

these basic facts, little more is known for certain about Chubby

Parker, though conjecture is plentiful. Clayton Jackson, a Gennett

Records sales manager in Chicago, claimed to have tracked Parker

down in a speakeasy to sign him to a Gennett contract after the

company had signed its deal with Sears. Charles Wolfe asserted that

Parker was a native of Kentucky, that he left WLS out of jealousy

over Bradley Kincaid's success, and that in the 1930s, he was still

living in Chicago but no longer in the music business. 54

There is also some confusion about Parker's banjo playing, as it

bears no sonic resemblance to more common traditional styles,

clawhammer (down-picking) and two- or three-finger up-picking. My

ears hear a plectrum, rather than fingers on the strings, and a

picking style similar to early-country guitar playing. Russell and

Meade must have heard something similar, for they both list Parker

as playing a tenor (or four-string) banjo. But a picture in a

Gennett catalog showed him holding a five-string banjo.

Beyond

these basic facts, little more is known for certain about Chubby

Parker, though conjecture is plentiful. Clayton Jackson, a Gennett

Records sales manager in Chicago, claimed to have tracked Parker

down in a speakeasy to sign him to a Gennett contract after the

company had signed its deal with Sears. Charles Wolfe asserted that

Parker was a native of Kentucky, that he left WLS out of jealousy

over Bradley Kincaid's success, and that in the 1930s, he was still

living in Chicago but no longer in the music business. 54

There is also some confusion about Parker's banjo playing, as it

bears no sonic resemblance to more common traditional styles,

clawhammer (down-picking) and two- or three-finger up-picking. My

ears hear a plectrum, rather than fingers on the strings, and a

picking style similar to early-country guitar playing. Russell and

Meade must have heard something similar, for they both list Parker

as playing a tenor (or four-string) banjo. But a picture in a

Gennett catalog showed him holding a five-string banjo.

Harry Steele, writing in 1936, claimed that when Parker was pressed into service as a folk singer–he was already singing on WLS–it was a role for which he was ill-suited. A more recent critic averred that Parker played the stereotypical role of "backward hillbilly." 55 An aural examination of Parker's recorded repertoire offers a contrary appraisal. The singer was comfortable with a variety of old-time songs, including songs from blackface minstrelsy, abolitionist songs, sentimental songs, and comic songs. On all his recordings, his singing was accompanied by his banjo. On some he added harmonica or whistling. His most famous song, "Little Old Sod Shanty on the Claim," was a remake of Will Hays's well-known "Little Old Cabin in the Lane," first published in 1871. One of the newer compositions Parker recorded, "See The Black Clouds A' Breakin' Over Yonder," was evidently written for Huey Long's populist campaign for the governorship of Louisiana. The fifty-six masters recorded by Parker comprised only twenty-nine different songs. Many songs he recorded at three or more of his nine recording sessions. Of these twenty-nine songs, only four were not classified by Meade as traditional.

Bradley

Kincaid's musical career, on the other hand, has been

well-chronicled. Born in 1895 in Garrard County in the Bluegrass

region of eastern Kentucky, he was raised in the foothills of the

Cumberland Mountains. His family and neighborhood both were full of

singers. His father swapped a foxhound for the guitar on which

Bradley learned to play. The first phase of his musical education

was thus rooted deeply in the folk music traditions of his home and

community. The next phase was as well. At age nineteen, he entered

the Foundation School at Berea College in neighboring Madison

County, where, after serving in the army during World War I, he

finished his High School degree at the age of twenty-seven. Berea

College is well-known for its institutional interest in traditional

culture, and Bradley's experiences there certainly solidified his

respect for the folk songs he learned at home. Yet when he arrived

in Chicago in 1924 to attend the YMCA College (later renamed George

Williams College), he busied himself directing glee clubs and church

choirs and became a member of the YMCA College Quartet. 56

Bradley

Kincaid's musical career, on the other hand, has been

well-chronicled. Born in 1895 in Garrard County in the Bluegrass

region of eastern Kentucky, he was raised in the foothills of the

Cumberland Mountains. His family and neighborhood both were full of

singers. His father swapped a foxhound for the guitar on which

Bradley learned to play. The first phase of his musical education

was thus rooted deeply in the folk music traditions of his home and

community. The next phase was as well. At age nineteen, he entered

the Foundation School at Berea College in neighboring Madison

County, where, after serving in the army during World War I, he

finished his High School degree at the age of twenty-seven. Berea

College is well-known for its institutional interest in traditional

culture, and Bradley's experiences there certainly solidified his

respect for the folk songs he learned at home. Yet when he arrived

in Chicago in 1924 to attend the YMCA College (later renamed George

Williams College), he busied himself directing glee clubs and church

choirs and became a member of the YMCA College Quartet. 56

The YMCA quartet opened the door for Kincaid to become part of the Barn Dance in 1926. When the quartet performed on a weekday show at WLS, the group's manager told Don Malin, the station's music director, about Kincaid's folk-song repertoire. Malin invited him to come back on Saturday and sing a few "old timers" on the Barn Dance. He did and soon became one of the first big radio stars in the United States. However, Kincaid had in fact aimed his career down a different path, toward formal music education. He even had to borrow a guitar for his Barn Dance debut. But the $15 weekly paycheck that came with being on the NBD was too much for a 1920s college student to refuse, and the hundreds of appreciative letters from listeners, which began arriving immediately, convinced him to give radio a try. 57

Bradley Kincaid, "the

Kentucky Mountain Boy" with his "hound dog guitar"–a replica of

which was soon offered for sale in the Sears catalog–was a big

favorite on the Barn Dance for the next four years, until he left

for WLW in Cincinnati. During his time at WLS, he discovered–upon

urging by station manager Edgar Bill–that a lucrative market existed

for his mountain folk songs. In April of 1928, he published a

songbook containing twenty-two of My Favorite Mountain Ballad

and Old Time Songs, which proved to be so popular with Barn

Dance listeners that it required five additional printings in the

next sixteen months. Two additional volumes were printed at WLS, and

ten more followed in the next fifteen years, during which Kincaid

worked mostly in the Northeast. He also discovered, again to his

surprise, that scores of people wanted to hear him in person. He

told of arriving in Peoria for his first booking through the WLS

Artists Bureau only to see people lined up for several blocks

outside the theatre, having no inkling they were there to see him.

He made several hundred dollars that night, and after a few years of

radio work, he had achieved a previously unimaginable level of

financial comfort.

Bradley Kincaid, "the

Kentucky Mountain Boy" with his "hound dog guitar"–a replica of

which was soon offered for sale in the Sears catalog–was a big

favorite on the Barn Dance for the next four years, until he left

for WLW in Cincinnati. During his time at WLS, he discovered–upon

urging by station manager Edgar Bill–that a lucrative market existed

for his mountain folk songs. In April of 1928, he published a

songbook containing twenty-two of My Favorite Mountain Ballad

and Old Time Songs, which proved to be so popular with Barn

Dance listeners that it required five additional printings in the

next sixteen months. Two additional volumes were printed at WLS, and

ten more followed in the next fifteen years, during which Kincaid

worked mostly in the Northeast. He also discovered, again to his

surprise, that scores of people wanted to hear him in person. He

told of arriving in Peoria for his first booking through the WLS

Artists Bureau only to see people lined up for several blocks

outside the theatre, having no inkling they were there to see him.

He made several hundred dollars that night, and after a few years of

radio work, he had achieved a previously unimaginable level of

financial comfort.

During his four years on WLS, Bradley Kincaid recorded eighty-five pieces, and another fifty-five before 1942. Like Parker, he recorded many songs at more than one session, often for different labels. In the final count, he recorded ninety-five songs, eighty-five of which are classified as traditional by Meade. His biggest hit was the traditional ballad, "Barbara Allen." Several other British ballads were in his repertoire, as well as a broad sample of American ballads, lyric folksongs, frolic songs, sentimental songs, and comic songs. All were recorded with Bradley's spare but solid guitar accompaniment.

Pretty Little Pink by Bradley Kincaid, 1930

Somebody's Waiting for You by Bradley Kincaid, 1934

Arkansas Woodchopper was the stage name for Luther Ossenbrink, but the Hayloft Gang more often called him ‘Arkie'. Born in 1906 in the town of Knob Noster in central Missouri (not, as often reported, in the Ozarks), Arkie had a thoroughly rural upbringing that introduced him to both the pleasures of country life–hunting, fishing, fiddling, and calling square dances–and the drudgery. "The last real labor I did on the farm was to clear 10 acres of honey locust," he told the Prairie Farmer, when he was brand new to the Barn Dance. He started in radio on KMBC, the Sears station in Kansas City, in 1928. He joined the National Barn Dance the next year, and stayed through the 1960s. Affable and multi-talented, he was a favorite of both listeners and fellow cast members. A WLS Family Album listed his talents as "‘plunking the guitar to accompany his cowboy or comedy songs; playing ‘lead fiddle' in the barn dance orchestra; ‘seconding' fiddlers with his banjo' or ‘calling off' for square dancers." 58 All of Arkie's talents were of a rustic variety. He was pictured playing his fiddle while holding it down against his chest, rather than in a conventional violinist's hold on the shoulder.

Between 1928 and 1931, Arkie, with just his guitar, recorded forty masters, comprising thirty-six songs. Thirty-two of his songs are classified as traditional by Meade, including a smattering of old-time cowboy songs, like "The Cowboy's Dream," and comic songs, e.g., "(Who Threw the Overalls in) Mrs. Murphy's Chowder." Most of Arkie's recorded songs were on sentimental themes of home, "Sweet Sunny South"; family, "Write Me a Song of My Father"; and love, "Prisoner at the Bar." Arkie did not return to the recording studio again for another ten years, when he recorded the eight square dance calls discussed in the previous section.

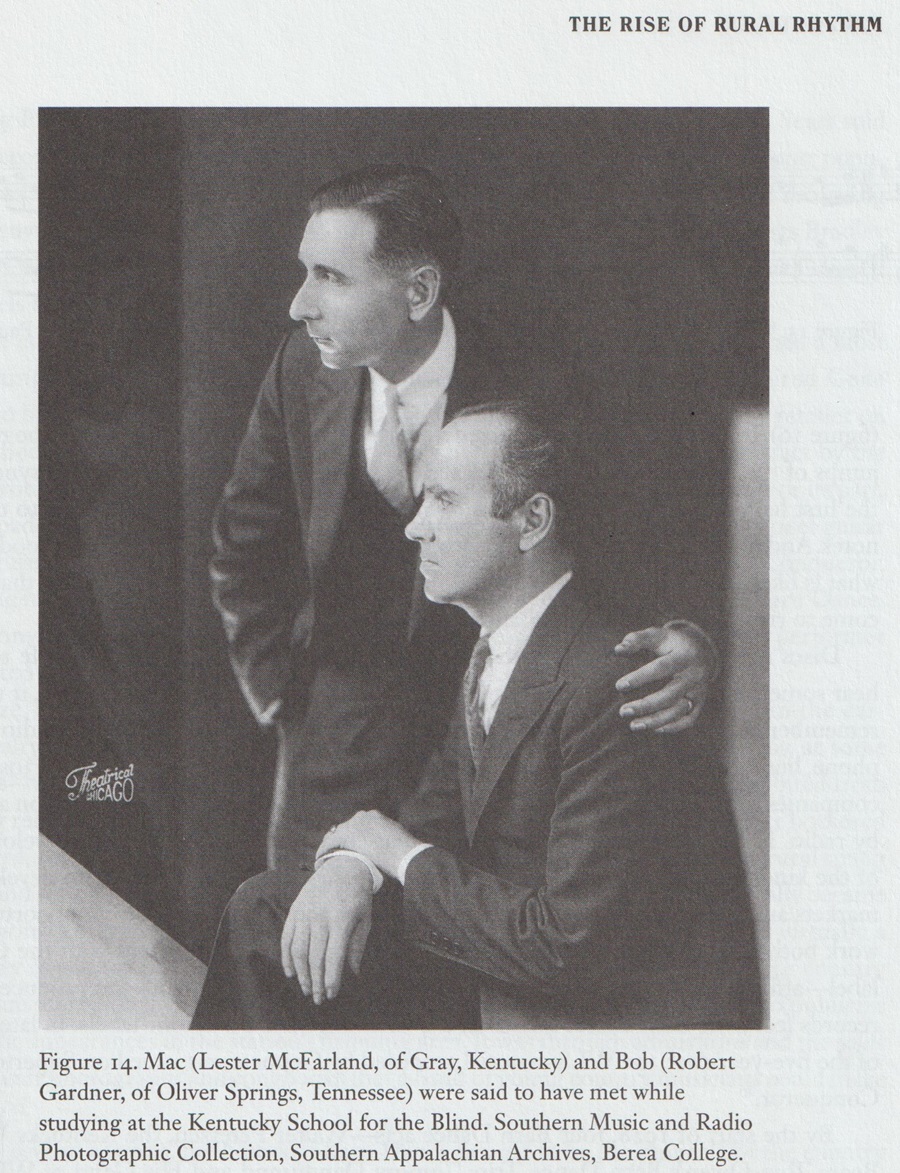

Mac & Bob were established stars of both radio and phonograph records when they joined the Barn Dance for the first time in 1931. Their initial tenure lasted until 1933, when they moved on to other stations. They returned to WLS in 1939, and stayed until their partnership broke up in 1950. Mac was Lester McFarland, born in 1902 in Kentucky, and Bob was Robert Gardner, born five years earlier in Tennessee. They met in 1915 at the Kentucky School for the Blind in Louisville, and embarked upon a full-time career in music in 1922; within three years they were favorites on WNOX in Knoxville, Tennessee. Multi-instrumentalists, their recordings, nevertheless, featured Mac on mandolin and Bob on guitar. They are often credited as being the first close harmony duet in country music and therefore as pioneering a sound that became prevalent in country music later in the 1930s with the emergence of many popular brother duets, like the Delmore Brothers, the Blue Sky Boys (the Bolick Brothers), the Callahan Brothers, and the Monroe Brothers. (The latter may have performed some vocal duets on the Barn Dance during their time as members of one of the NBD's square dance troupes–a time period that coincided with Mac & Bob's first tenure.) Still, In Charles Wolfe's assessment, "most of their music sounds too restrained and polite to modern ears." 59

It is true that Mac & Bob's duets clearly lack that intangible vocal affectation that eventually pervaded southern-style country vocals–in recent years it has been dubbed "twang" and is now regarded by many as an essential element of authentic country music. But their stature as broadcast and recording artists before 1942 demands for them a respectful hearing. They recorded 241 separate songs on 282 masters. In addition, McFarland recorded fourteen numbers with George Reneau, as the Gentry Brothers, and at least one solo. Mac & Bob were also half of the vocal quartet, the Old Southern Sacred Singers (for which they also provided instrumental accompaniment), which recorded thirty sides between 1926 and 1929. 60 At least 150 of the songs recorded by Mac & Bob, and Meade classified all but three of those waxed by the Old Southern Sacred Singers as traditional.

Just Plain Folks by Mac & Bob, 1929

Where We'll Never Grow Old by the Original Southern Sacred Singers, 1926

A further analysis of Mac & Bob's repertoire is long overdue but is beyond the scope of the present essay. Still, I would add one observation, that there is a noticeable overlap between their recorded body of work and that of the original Carter Family of Maces Springs, Virginia, one of country music's most preeminent vocal ensembles. At least thirteen songs made famous by the Carter Family were first recorded by Mac & Bob, including "Are You Tired of Me Darling," (Bury Me Beneath) "The Willow Tree," and "When the Roses Bloom Again." Conversely, only one song the two groups had in common was recorded first by the Carter Family.

Modern Folk Song Artists

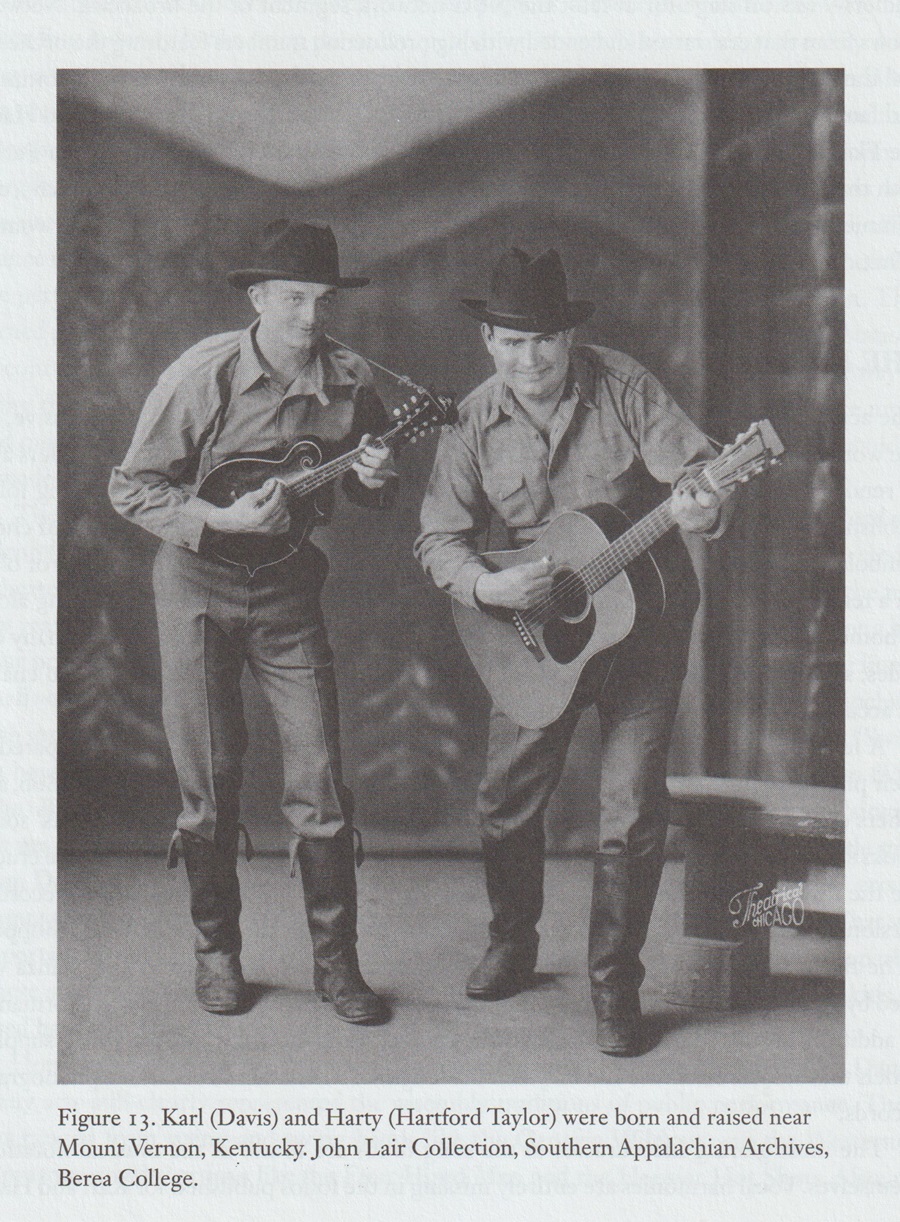

In 1930, John Lair brought the first southern string band to the National Barn Dance, the Cumberland Ridge Runners. The first lineup–Kentuckians all–included Lair, the group's manager on jug, Gene Ruppe on fiddle (and perhaps banjo), Doc Hopkins on banjo (and perhaps guitar), Karl Davis on mandolin, and Hartford Taylor on guitar. A year later, Slim Miller, a native of Lizton, Indiana, had replaced Ruppe on fiddle, and Hugh Cross, an established recording artist from Atlanta, took over on banjo for Doc Hopkins. By the time another year had passed, Clyde Julian "Red" Foley, had joined the Ridge Runners on bass, and within the next year, Hugh Cross departed, leaving banjo-less this manifestation of the Ridge Runners. 61

In fact, the Ridge Runners were an umbrella group for a variety of smaller performing units. The most important of these was Karl & Harty–Karl Davis and Hartford Connecticutt Taylor, both born in 1905 in Mt. Vernon near Kentucky's Eastern Coal Field–who initially broadcast on WLS and made records as the Renfro Valley Boys. Their close vocal harmony with guitar and mandolin accompaniment followed the same arc that began with Mac & Bob and led to the Monroe Brothers. Red Foley, from Madison County in the Eastern Knobs region of Kentucky, joined the band in Chicago in 1932, when he was only twenty-two years old. Lair quickly paired him with another rookie, nineteen-year-old Myrtle Cooper, to form the comic singing duo of Lulu Belle and Burrhead. Then, perhaps to balance Lulu Belle's gum-smacking, boy-chasing, manic, and sassy persona, Lair added a sweet-voiced, contentedly domestic, and purely virtuous "Sunbonnet Girl," whom he named Linda Parker. Parker's real name was Jeanne Muenich; and though Parker's signature song on the Barn Dance was a gem of Victorian sentimentality, "Bury Me Beneath the Willow," Muenich had gotten her start in music as a night club singer. 62

Take Me Back To Renfro Valley by Linda Parker with the Cumberland Ridge Runners, 1933

Just One Little Kiss by Red Foley, 1934

When Linda Parker died tragically from an infection contracted while on a WLS road tour in 1935, the whole Barn Dance family mourned in a sustained public display. Karl & Harty recorded a tribute piece, "We Buried Her Beneath the Willow (Ridge Runners' Tribute to Linda Parker)," which was quickly covered by another WLS artist, Sally Foster [Louise Rautenberg], accompanied by the Travelers. Within a short time, the Cumberland Ridge Runners went their separate ways, and even Karl & Harty left WLS for local rival WJJD's Suppertime Frolic. Red Foley became a featured artist, along with Slim Miller and the Girls of the Golden West, on the Pinex Merrymakers, a series of transcribed programs perhaps managed by John Lair. By 1937, Lair, Foley, and Miller had relocated to WLW in Cincinnati, where Lair began to develop his own empire, The Renfro Valley Barn Dance. Miller would stick with Lair for the rest of his career. Karl & Harty, on the other hand, returned to WLS and the National Barn Dance in 1941, where they again used the name the Cumberland Ridge Runners for a quartet that included a reunion with Doc Hopkins and added fiddler Buddy McDowell.

Between 1931 and 1942, Karl & Harty recorded a total of seventy masters comprising sixty-six songs. The fourteen recordings made in 1935 and 1936 were issued as by Karl & Harty "Of the . . . " or "Acc. by the Cumberland Ridge Runners." Six additional numbers were issued under the band's name, and four others by the band featured Linda Parker. Of this array, Meade classified as traditional seventeen numbers by Karl & Harty, four by the Ridge Runners (counting Meade's obvious oversight of "Nobody's Darling on Earth), and only one of Linda Parker's songs. According to Charles Wolfe, the daily grind of radio forced Karl & Harty to hunt up more songs, learning many new pieces from Carter Family records and old hymnals. They also turned to writing their own songs, at which they both proved adept. Karl Davis penned their first big hit, "I'm Here to Get My Baby Out of Jail," and the later, often-covered, "Kentucky." They also had a silent partner in Frank Johnson, who signed his songs with the name "Pat McAdory. He collaborated with the duo on their second hit, "The Prisoner's Dream." 63

As for Karl's and Harty's associates in the Ridge Runners: Doc Hopkins recorded thirty-five total songs, in 1931-1932, 1936, and 1941. Since Hopkins was later known as "America's Favorite Folk Singer" on his own radio show on WJJD, it is somewhat surprising that Meade classified only a dozen of his recorded songs as traditional. Red Foley recorded five traditional songs, out of the twenty he waxed in the mid-'30s. Hugh Cross made no records while a member of the Ridge Runners.

Sally's Not the Same Old Sally by Pinex Trio with Slim Miller (Red Foley & Girls of the Golden West), 1938

Wreck Of Old 31 by Doc Hopkins, 1941

When the Curtains of Night by Doc Hopkins & His Boys, circa 1945

Lulu Belle & Scotty, Myrtle Cooper and Scott Wiseman, were both born in North Carolina; she in 1913, and he in 1909. But they met in Chicago as fellow cast members of the National Barn Dance, and it was in the Old Hayloft that they became musical partners and, later, husband and wife. Young Myrtle Cooper's family was constantly on the move but settled in Evanston, Illinois, when she was sixteen. Just three years later, Cooper's father brought his big-voiced daughter down to WLS and pestered the station's executives until they auditioned and hired his daughter. She was immediately given the stage name of Lulu Belle–which Myrtle Cooper Wiseman carefully spelled as "Lula Belle" for the rest of her days. Her mother helped design her first costume, which also proved to be long-lasting: a gingham dress with pantaloons and high-topped shoes. John Lair completed the construction of her stage persona by sending her off to a theatre to observe the rube starlet in the popular vaudeville act, the Weaver Brothers & Elviry. Following Elviry's lead, Lula Belle became feisty, smart-alecky, mischievous, and boy crazy. The Barn Dance audiences loved it! In 1936, Lulu Belle was voted "Radio Queen," in a popularity poll run by Radio Guide magazine. 64

Scott Wiseman, on the other hand, was shy, soft-spoken, and serious. He learned to play guitar, banjo, and harmonica, and fell under the influence of Bradley Kincaid. Like Kincaid, Wiseman began to collect traditional songs from mountain singers near his home in Boone, North Carolina. He even met Kincaid on one of the latter's song-collecting trips, and the radio star told him he had a future in radio. But Wiseman wanted to finish his college education first, which he did at Fairmont State College in West Virginia. While a student, he got his first radio job announcing at WMMN in Fairmont and adopted the nickname Skyland Scotty. In 1933, he successfully auditioned for the Barn Dance and joined a long line of traditional folk singers on the show that stretched back through Arkie and Bradley Kincaid to Chubby Parker. 65

Shortly after Wiseman arrived in the Old Hayloft, Lulu Belle's comic partner, Red Foley, married Eva Overstake of the Three Little Maids. The new wife's jealousy broke up the Lulu Belle and Burrhead team. John Lair instructed Lulu Belle to work up some routines with Skyland Scotty. They clicked with each other and with their audiences, and a decades-long radio partnership was on its way. When they married in an on-air ceremony in 1934, Lulu Belle no longer had to try to catch a man. So the theme of her feistiness shifted to the comic "battle of the sexes," and audiences loved it even more. 66

Going Out West This Fall by Lulu Belle & Burrhead (Red Foley) , 1934

Sugar Babe by Lulu Belle & Scotty, 1935

In 1933 and '34, Scott Wiseman recorded fourteen sides in Chicago for the Conqueror and Bluebird labels. Meade classified ten of these pieces as traditional. Then from 1935 to 1940, Lulu Belle and Scotty recorded thirty-one more pieces for various labels in the ARC family. Of these thirty-one, Meade classified nineteen as traditional. Many of the newer pieces–i.e., modern folk songs, to use George Biggar's label–that worked so well in their act were novelty numbers, such as "When I Yoo-Hoo in the Valley" and "Daffy Over Taffy" (which Lulu Belle had originally recorded with Red Foley). Scott Wiseman also proved to be a very capable songwriter. Besides having a hand in composing–along with Bascom Lamar Lunsford of the Asheville area in North Carolina–the classic "Mountain Dew," Scotty's most popular hit from this era is the bittersweet love song "Remember Me," which the duo recorded in 1940.

From Jerusalem to Jericho by Lulu Belle & Scotty, 1935

Deep Elem Blues by the Prairie Ramblers, 1935

If ever a group in country music history deserved the serious attention of journalists, scholars, and reissue producers–but was instead almost completely overlooked–it was the Prairie Ramblers. Formed originally as the Kentucky Ramblers around the talents of boyhood friends Charles "Chick" Hurt and Jack Taylor–both born in 1901–they combined, respectively, mandola and tenor banjo, guitar, and bass. They soon added another musician from their home region of the Pennyrile in south-central Kentucky: Floyd "Salty" Holmes (born in 1909) on jug and harmonica. Perhaps the key addition to the group was the versatile young left-handed fiddler, David Shelby "Tex" Atchison, born in 1912 on a farm near Rosine (Bill Monroe's home area.) in Kentucky's western coal field. Atchison was an impatient teenager who, because of a broken wrist, learned to play left-handed on a right-handed fiddle. Before his twentieth birthday, Atchison was performing live on radio in Evansville, Indiana. Besides fiddle, he also played clarinet and sax in a band that did both old time country- and jazz-influenced pop music. He joined the Ramblers in time for that band's radio debut in 1932 on WOC in Davenport, Iowa. 67

The next year, the Ramblers moved to Chicago, joined the cast of the Barn Dance, and changed their name to the Prairie Ramblers (perhaps in deference to the Prairie Farmer company that issued their paychecks). They were initially teamed with female vocalist, Dixie Mason. Although she recorded two sides in 1933 with just guitar accompaniment, she never recorded with the Ramblers. But by the end of the year, when the band headed to the Victor studios in Chicago for their first recording session, they were joined by Patsy Montana, who would work with them steadily for the next seven years–on the air, on records, and on personal appearances. In 1934, Patsy and the Ramblers headed for New York to make records for Vocalion and the ARC labels.

Looking back, Atchison claimed that their year-long New York hiatus was quite beneficial to the band: "We left Chicago as an Old-Time string band and we came back from New York as a cowboy band." 68 Perhaps the greatest benefit was that the Ramblers became more professional and were better able to market themselves using their new cowboy image. Did they remake themselves into a western swing band, as some historians have suggested? The western swing sound was emerging in Fort Worth and Tulsa, just as the Ramblers headed off for New York; and they clearly became one of the first bands east of the Mississippi River to promote a similar merger of swing music and rural sensibilities. However, the swing tendencies had always been present to some extent in the playing of Tex Atchison. Swing was simply an addition to their bag of tricks, for when they returned to Chicago, they picked right up again with the old-time frolic songs, fiddle breakdowns, and gospel numbers they had always played. The biggest change to the sound of the Prairie Ramblers came when Tex Atchison left WLS in 1937–he did his last recording sessions with the Ramblers in 1938–to find work in the music and film industries of California. Atchison was soon replaced by Alan Crockett, a young fiddler who had grown up in the California country music scene as part of the Crockett Family Mountaineers. 69

Jim's Windy Mule by the Prairie Ramblers, 1935

Yip Yip Yowie, I'm an Eagle by the Prairie Ramblers, 1935

The Prairie Ramblers recorded 257 masters that yielded 228 different songs. Meade classified less than half of them as traditional. It is worth noting that a lot of the old-time frolic and gospel songs that they recorded were later covered by the Monroe Brothers, such as "Gonna Have a Feast Here Tonight" and "What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul." The Prairie Ramblers also had an alter ego, the Sweet Violet Boys, under which name they cut some rather risque material that probably was never performed in the Old Hayloft.

The Massey family, known as the Westerners on radio and most often as Louise Massey & the Westerners on phonograph records, arrived at the Barn Dance in 1933 as seasoned veterans. They started out as a family band, led by fiddler Henry "Dad" Massey, who soon retired to his ranch in Roswell, New Mexico. The Massey children who carried on, included Louise (born 1902), the lead singer and sometimes pianist, Allen (born 1907) on guitar, Curt, also known as Dott (born 1910) on fiddle and trumpet, and Louise's husband, Milt Mabie (born 1900) on bass. After a few years of touring for the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, they landed a radio job in Topeka, and then at KMBC in Kansas City. The stayed at KMBC for five years, adding accordionist Larry Wellington to the band, and were heard by George Biggar, who brought them to WLS in 1933. After two years of weekday programs and the Saturday night Barn Dance, the Westerners moved on the New York City, where they joined the cast of NBC's popular variety program, Show Boat. By 1940, they had come back to Chicago for a second and longer stay in the Old Hayloft. 70

Between 1933 and 1942, Louise Massey & the Westerners recorded 138 masters of increasingly sophisticated and pop-influenced modern folk songs. Meade classified only twenty-seven of their recordings as traditional, and a large share of these were instrumental dance tunes.

Honeysuckle Schottische by the The Westerners, 1935

Tug Boat & Piney Woods by the Henry "Dad" Massey, 1935

While in New York, they brought Dad Massey into the ARC studios to record seven traditional fiddle tunes (one disc was a medley of two hornpipes). In 1939, they did the same in Chicago, and the senior Massey recorded four more hoedowns, which, sadly, were never issued. The Massey's are best known for their modern folk songs, like "Huckleberry Picnic," "The Honey Song," and the most famous of all, "My Adobe Hacienda," written by Louise.

Going Down To Santa Fe Town by the The Westerners, 1934

Gals Don't Mean a Thing by the The Westerners, 1942

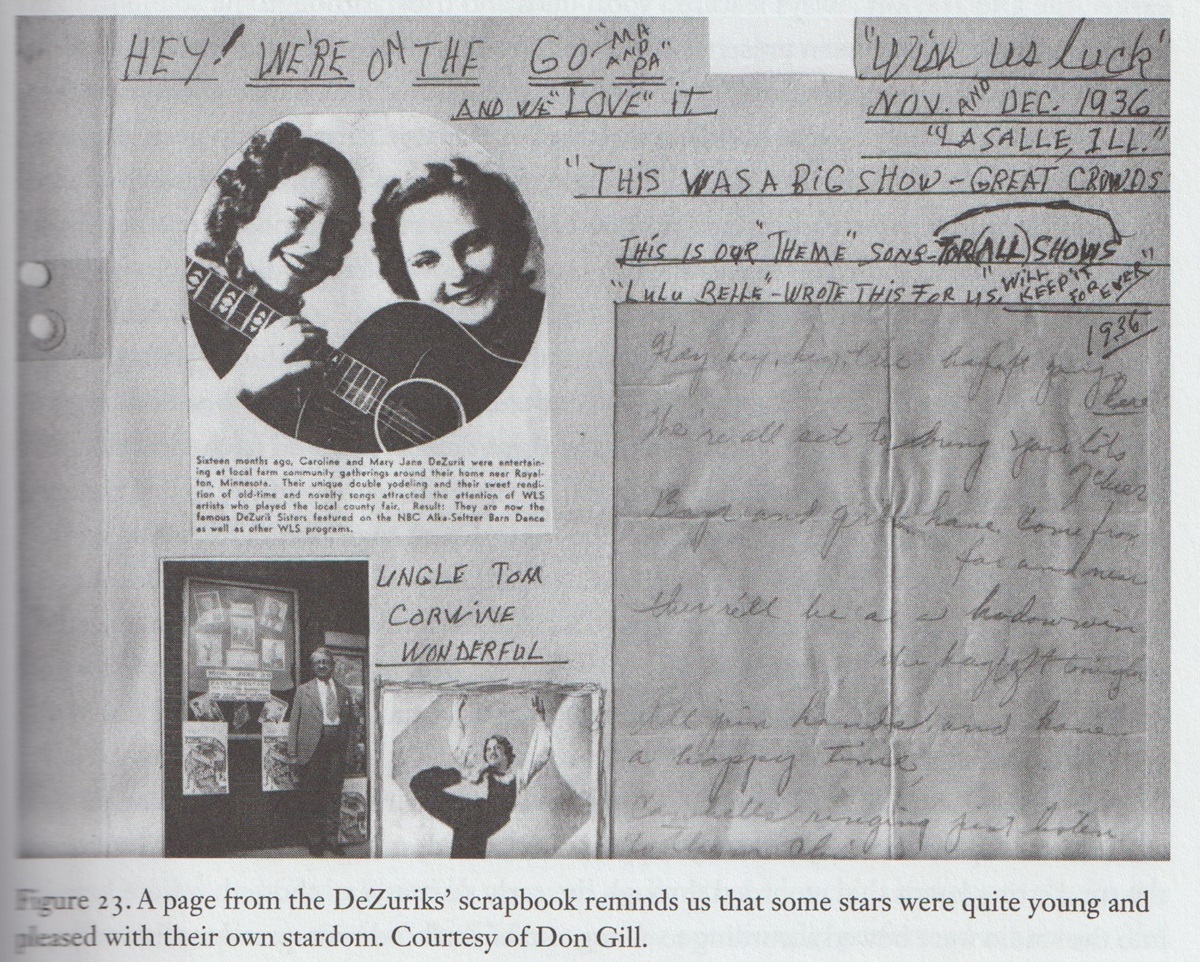

One of the most distinctive musical acts to join the National Barn Dance was the Dezurick Sisters raised on a farm near Royalton, in the center of the state of Minnesota. Carolyn (born 1919) and Mary Jane (born 1917) were part of a musical family of Dutch heritage that included a fiddling father, an accordion-playing brother, and five sisters (out of six) who could sing and play the guitar. While doing chores, the sisters' ears were open the natural music made by animals around them. They incorporated imitations of these sounds into elaborate trick yodels and novel harmonies that won them many amateur talent contests in central Minnesota. A representative from the WLS Artists Bureau caught their act and invited them to Chicago, where they were hired for the Barn Dance in November of 1936. Their stay was lengthened when Carolyn wed Rusty Gill, a staff guitarist and member of the Hoosier Sod Busters, in 1940. Less than a month later, Mary Jane married Augie Klein, a WLS staff accordionist who appeared on the NBD with the Hill Toppers. 71

Arizona Yodeler by the Dezurick Sisters, 1938

Go to Sleep My Darling by the Dezurick Sisters, 1938

Peach Pickin' Time in Georgia by the Cackle Sisters (aka Dezurick Sisters), circa 1940

But the DeZuriks' stay in Chicago became more complicated when they were engaged by Purina Mills in 1937 for a series of transcribed programs called Checkerboard Time. Because of contractual agreements, the DeZuriks appeared on the transcriptions as the Cackle Sisters. Several other NBD artists–the Maple City Four and Otto & the Novelodians–joined the Checkerboard cast as well, for it was broadcast in all forty-eight states. In 1938, the DeZurick Sisters recorded six songs for Vocalion, the only commercial records they made before 1942. 72 Meade deemed only one of these songs traditional.

A couple of lesser-known modern folk song artists who were part of the Barn Dance in the mid- to late 1930s should also be mentioned. Eddie and Jimmie Glosup were two brothers from Posey, Texas, who used the stage name Dean. Eddie came to Chicago in 1926, seeking a career in music. After a sojourn in Shenandoah, Iowa, and radio work in Yankton, South Dakota, and Topeka, Eddie reunited with his brother and returned to Chicago in 1934 to join the National Barn Dance. They stayed in Chicago until 1937, when Eddie left for Hollywood and a new career as a singing cowboy in the movies. 73 In 1934 and '35, the Dean Brothers recorded twenty-nine sides in the Windy City. Only a few of them were western songs. Meade classified even fewer as traditional songs, four (five, if we add in Meade's omission of "Get Along Little Dogies") in all. Fred Kirby, another singer of new country songs, came to the Barn Dance in 1940 from North Carolina, where he had recorded as Fred Kirby & his Carolina Boys. Earlier in the 1930s, he had worked with Cliff Carlisle. Between 1932 and 1938, Kirby recorded forty-eight songs, only five of which were deemed traditional according to Meade's criteria. 74

radio show excerpts by Eddie & Jimmie Dean, circa 1935

My Carolina Sweetheart by Fred Kirby, 1936

Western Song Artists

As should be expected, Gene Autry's name has been mentioned frequently in this essay. He was one of the dominant figures in the field of country music before World War II, and even after the war. Accordingly, he is the most famous performer who was ever a part of the Hayloft Gang. It seems strange, then, that there is so little institutional memory of Autry on the part of WLS and the Prairie Farmer. A single picture of Autry is all that appeared in the WLS Family Album. The amnesia was mutual, for in his autobiography, Autry gave only a cursory mention to the show and the station that helped launch him to fame. 75

Born in Tioga Springs, Texas, in 1907, Orvon Gene Autry was raised in Oklahoma in that state's second decade of statehood. His mother taught him to play guitar, and he learned to sing in the church where his grandfather served as pastor. As a teenager, he traveled with a medicine show; and as a twenty-one-year-old, he undertook a trip to New York City, where his first attempts to record were unsuccessful. Back in Oklahoma, he returned to his job as a railroad telegrapher but also got a radio gig on KVOO in Tulsa. He billed himself as the Oklahoma Yodeling Cowboy, and by 1929 began his very prolific career as a recording artist. 76

I'll Always Be A Rambler by Gene Autry , circa 1931

Valley In The Hills by Gene Autry , circa 1931

Many of Autry's first records were vocal duets with Jimmy Long, a fellow railroad employee. But what really made established his early career was that he could successfully imitate the blue yodel of early country music giant, Jimmie Rodgers. Not only did Autry cover a number of Rodger's pieces, he contributed many blues pieces of his own. Yet, by the time Autry left Chicago to star in Hollywood westerns, he had remade himself into a western singer. Also, during his time in Chicago, because of the incredible success of "Silver Haired Daddy of Mine," he was encouraged to focus more on sentimental songs. 77 On many of his sessions during his Chicago days, the Prairie Ramblers accompanied Autry.

Another

too-often overlooked gem of the National Barn Dance was the sister

act, the Girls of the Golden West. The sisters were Mildred

and Dorothy Goad, born in 1913 and 1915, respectively, on a farm in

southern Illinois. By the time Millie was fourteen, the Goad family

had moved first to Mt. Vernon, and then to East St. Louis on the

other side of Illinois. The sisters learned to sing naturally at

home, for their mother played guitar and sang and was known to

perform in public at a church gathering. Dollie learned guitar from

her mother. Harmony also came easily and unstudied, as Millie

related in a 1978 interview, explaining that her mother "always had

a natural ear for harmony just like I do. . . . When I hear a note,

I hear the harmony note to it, so I got that from my mother." 78

Another

too-often overlooked gem of the National Barn Dance was the sister

act, the Girls of the Golden West. The sisters were Mildred

and Dorothy Goad, born in 1913 and 1915, respectively, on a farm in

southern Illinois. By the time Millie was fourteen, the Goad family

had moved first to Mt. Vernon, and then to East St. Louis on the

other side of Illinois. The sisters learned to sing naturally at

home, for their mother played guitar and sang and was known to

perform in public at a church gathering. Dollie learned guitar from

her mother. Harmony also came easily and unstudied, as Millie

related in a 1978 interview, explaining that her mother "always had

a natural ear for harmony just like I do. . . . When I hear a note,

I hear the harmony note to it, so I got that from my mother." 78

In 1930, after a short time at WIL in St. Louis, the Good Sisters (they changed the spelling), established themselves on the larger KMOX. They started on a morning show and soon joined the Saturday night program called County Fair. At some point, they were given the name the Girls of the Golden West and began to focus on traditional cowboy songs and other "western-type songs," even dressing the part with elaborate, homemade western costumes. After a sojourn to Abilene to broadcast programs that, by means of a relay, were aired from XER in Mexico, the sisters were booked by Glenn Snyder to join the Barn Dance in 1933 (though in Millie's memory, it "was about 1931"). 79 Whatever the year, at least one of the Girls was still just a teenager. They stayed at WLS through 1937, during which time they helped several other young women land roles in the Old Hayloft. As part of the Pinex Merrymakers with Red Foley, they also moved to Cincinnati in 1938 and latched on with the Boone County Jamboree, a show started by George Biggar on WLW, "The Nation's Station."

Between 1933 and '38, the Girls of the Golden West recorded sixty-four harmony duets, always accompanied only by Dollie's guitar. Many of their numbers featured tight harmony yodels. Meade classified seventeen of these songs as traditional, including such cowboy ballads as "Bucking Bronco" and "Lonely Cowgirl." The major part of their recorded repertoire was of newer western songs, like "By the Silvery Rio Grande" and "Take Me Back to My Boots and Saddle." They also waxed some memorable love songs, such as "Roll Along, Prairie Moon" and, perhaps their best known, "There's a Silver Moon on the Golden Gate."

Patsy Montana was a true pioneer. Her self-penned, 1935 hit recording, "I Want to Be a Cowboy Sweetheart," was the first disc by a woman in the country music field to sell a million copies. Of greater importance is that her work and success created space for women in a business that, like so many others, had been dominated by men. Mary Bufwack and Robert Oerman capture the essence of her contribution: "In her songs and stage presence she rewrote the myth of the American cowboy to include women, providing a new role option for women country singers, and popularizing an innovative independent female image." 80

Patsy Montana was born Ruby Blevins in 1912 in Hope, Arkansas, the sole daughter in a family of eleven children. By the time she was a teenager, she had learned to play guitar, studied violin in high school, learned songs from Jimmie Rodgers records, and most importantly, had figured out on her own how to yodel by singing along with Caruso records left behind by the previous tenant in their rented house. In 1929, after graduating from high school, Ruby headed for California, where she planned to live with her brother, enroll at the University of the West (now UCLA), and study violin. These plans were diverted, in part, when she entered and won a talent contest–by singing two Jimmie Rodgers songs–and earned the right to appear on the Breakfast Club on station KMTR. 81

On KMTR, Ruby was known as "The Yodeling Cowgirl from San Antone" and caught the attention of Stuart Hamblen on KMIC. He invited her to join his troupe as part of a trio called the Montana Cowgirls, for which Ruby Blevins adopted the stage name Patsy Montana. The Cowgirls were big favorites in southern California, and Patsy got plenty of experience riding in rodeos and singing on radio. But the trio split up in the early years of the Great Depression, and Patsy headed back to Arkansas. A week-long booking at KWKH in Shreveport led to an opportunity to travel east to serve as accompanist at a Victor session for Jimmie Davis, and to record four numbers on her own.

In 1933, she was back home, where her mother had cooked up quite a plan. She had been corresponding with the Girls of the Golden West, stars on her favorite radio show, and told them all about Patsy. Seizing the good fortune of a gigantic, hundred-pound watermelon produced by the family garden, Mrs. Blevins urged two of her sons to take Patsy along and go show it off in Chicago at the World's Fair. Three Blevins headed north, and while two took the watermelon into the Fair, Patsy went downtown to the Eighth Street Theatre, where she found the Good sisters backstage. Dolly told her, "Honey . . . The Prairie Ramblers are looking for a girl singer. If you're interested, go sign up." She got the job and began the hectic life of a full-time country artist–she always described herself as a "western" singer, and always sewed her own western costumes. Her daily schedule with the Ramblers included broadcasts on Wake Up and Smile each morning at 5:30 and 7:30, followed by a road trip to a personal appearance in the station's listening area, followed by yet another drive back home, with hopes for a few hours of sleep before the alarm rang to start it all again. And, of course, there was the Barn Dance on Saturday nights. Even her 1934 marriage to Paul Rose–business manager for Mac & Bob–and the arrival of baby Beverly the following year, did not slow Patsy's career. She remembers that when she and the Ramblers, in 1936, were first scheduled for the coveted NBC network segment of the Barn Dance, they really had made it, for then they would be heard "coast-to-coast." 82 As noted earlier, the Prairie Ramblers with Patsy Montana were voted one of the three most popular acts on WLS in 1937.

Echoes from The Hills by Patsy Montana, 1936

Patsy Montana recorded eighty-seven masters with the Prairie Ramblers between 1933 and 1940. Add in the four pieces recorded in 1932–before she landed her spot on the Barn Dance, and the thirteen recorded in Dallas in 1941, after she left Chicago–and her total output on pre-1942 discs is 104 masters, yielding eighty-two separate songs. Meade classified only three of these as traditional. A large portion of her repertoire was songs she had written. Her earliest signature piece was, "Montana Plains," an adaptation of Stuart Hamblen's "Texas Plains." The phenomenal success–slow, steady, and persistent–of "I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart," led her record label, the ARC group, to urge her to come up with more of the same. She eventually did, with the likes of "I Wanna Be a Cowboy's Dreamgirl." But Patsy proved to be a prodigious and effective songwriter, especially in her use of western themes: "The She Buckaroo," "Cowboy Rhythm," "Gold Coast Express" (co-authored with Stuart Hamblen), and "Old Nevada Moon" and "My Poncho Pony" (both co-written with Lee Penny).

Novelty Musicians

From the second week of the National Barn Dance on through 1929, one of the regularly-scheduled performers was "Kentucky Wonderbean, harp." By the end of that first summer, the Wonderbean was clearly identified as Walter Peterson. Not much is known about Peterson himself. He performances featured his "Doubled Barrelled Shot-gun": he cradled a guitar in his arms while simultaneously blowing on a ten-hole harmonica held in a wire rack around his neck. During the same period, Dynamite Jim, a native Hoosier whose real name was Harry Campbell, Jr., also performed on WLS with a similar get-up, dubbed a "cap and fuse." 83 Between 1924 and 1927, Peterson recorded twenty-two masters–many of them medleys of old familiar tunes, and all were instrumentals only. Half of them are listed as traditional in Meade. In 1928, the Kentucky Wonderbean made one final recording: a vocal version of a modern folk song, "My Blue Ridge Mountain Home."

Medley of Old Timers, Pt. 1 by Kentucky Wonderbean (aka Walter Petersen), 1924

Farming By the Fire by Pie Plant Pete (aka Claud Moye), 1935

A third NBD musician who paired guitar and harmonica in a rack–his "two cylinder corn cob crusher"–was Pie Plant Pete. In real life, he was Claud Moye, born in 1906 and reared on a farm in Gallatin County, Illinois, near Shawneetown. Pete joined the Barn Dance in 1927 and stayed through 1930. In 1929, he headlined a touring unit known as the WLS Show Boat Juniorand and was seldom heard on the broadcasts. In 1929 and '30, he recorded twenty-six numbers for Gennett, many released under the name Asparagus Joe. In 1934, after he had left WLS for WTAM in Cleveland, Pete recorded another twenty-two songs. All of his Gennett sides, and all but seven of the 1934 sides, were classified by Meade as traditional. 84

Good Old Turnip Greens by Pie Plant Pete (aka Claud Moye), 1930

Sand Will Do It by Pie Plant Pete (aka Claud Moye), 1930

Finally, the National Barn Dance tradition of comic-novelty groups must at least be mentioned, even though they cannot be given the attention deserved. The most famous was the Hoosier Hot Shots, who were formed in 1932 at WOWO in Fort Wayne, Indiana, by remnants from Ezra Buzzington's Rustic Revelers. The next year they came to WLS to join a sponsored program with comedian Uncle Ezra [Pat Barrett]. When they arrived in Chicago, they were still a trio of multi-instrumentalists, all born and raised in Arcadia, Indiana. Charles Otto "Gabe" Ward held forth on clarinet and sometimes saxophone; Paul "Hezzie" Triestch was a wizard of the washboard and slide whistle–"Are you ready, Hezzie?" was their signature salute–and Ken "Rudy" Treitsch was the rhythm section on guitar and tenor banjo. They were soon joined by Illinois native Frank Kettering on bass and guitar. The Hot Shots were a Barn Dance favorite until 1944, when they left for California. 85

Meet Me Tonight in the Cow Shed by Hoosier Hot Shots, 1942p>

Ida, Sweet As Apple Cider by Hoosier Hot Shots, 1938/p>

Bass Blues by Ezra Buzzington's Rustic Revelers, circa 1930

Another long-time audience favorite was the Maple City Four from LaPorte, Indiana. Primarily a vocal quartet, they were also known as cut-ups who devised a musical instrument out of a shower-hose and frequently tried the most outlandish antics to cause Arkie to break into laughter when he was in the middle of his featured number. Most of the other comedy and novelty music groups in the Old Hayloft were instrumental groups, such as the Four Hired Hands from Gary, Indiana, the Novelodeons, and Otto & the Tune Twisters. The latter two were essentially comprised of the same personnel and were led by Ted "Otto" Morse. The Hoosier Sod Busters, who started on WLS in 1933, featured a wide and sometimes weird array of harmonicas played by Reggie Cross, with guitar accompaniment by Howard Black. In 1939, guitarist and singer Rusty Gill joined them. Apparently, the Sod Busters never made commercial recordings.

That Old Gal of Mine by Maple City Four, circa 1952

Boy Oh

Boy Oh Boy by the Harmoneers, circa 1945

(Possibly led by Reggie Cross, formerly of the Hoosier Sod Busters.)

Summing Up the National Barn Dance

In spite of all the old 78rpm recordings I have listened to, the actual sounds of the early National Barn Dance remain elusive. Of the four network shows that I have heard, the only artists covered in the previous sections who appeared were the Arkansas Woodchopper, Lulu Belle & Scotty, and the Hoosier Hot Shots. And Arkie did no singing, only a smattering of square dance calls! To be honest, I am pretty disappointed with the music I hear on the air-check recordings. To be sure, it is great to experience the spirit and exuberance of the live broadcasts, to hear the comic sketches of Uncle Ezra and Pat Buttram, and to catch hold of the familiar friendliness of announcer Joe Kelly: "Hello, hello, hello everybody, everywhere! How's Mother and Dad and the whole family?" But there is vast dissonance between the music on this small sample of NBC network broadcasts and the vibrant and rustic old-time styles found on the phonograph records by early artists who made "the rafters ring in the old hayloft." Others have tried to deal with this disparity between the image of the National Barn Dance and the preserved broadcast evidence. For instance, Wayne Daniel noted, with a tone of polite objectivity, that "the Barn Dance was a variety show similar in format to other contemporary radio variety shows," and followed with a hopeful suggestion: "Perhaps the non-network broadcast segments of the show featured a higher ratio of ‘hillbilly' and ‘western' material." 86

I am convinced that Daniel's latter suggestion is correct, and therein lies the key to understanding the National Barn Dance: it encompassed so much more than the sixty-minute segment heard weekly on the NBC Blue network. It is possible to talk about five overlapping aspects of the Barn Dance. First, all Saturday-night programming on WLS, from 7:30 to midnight, was generally understood by listeners as the National Barn Dance. Second, various segments of what went out over the WLS airwaves were plainly titled the National Barn Dance. In the typical program lineup from 1933 quoted earlier, these programs ran from 7:30 to 8:00, and from 11:00 to midnight. Third, beginning in 1932, the National Barn Dance brand was also applied to each of the two-hour-long shows staged before large audiences at the Eighth Street Theater. The two on-air segments identified in the previous point filled only a portion of the running time of the theater shows. According to Slim Bryant, there were portions of the show at the Eighth Street Theater that were not broadcast. Fourth, shorter segments of the show aired with the name of a sponsor, like the Aladdin Barn Dance Frolic or the Keystone Barn Dance Party. The Alka-Seltzer sponsored network segment, the most famous of these, was broadcast live from the Eighth Street Theatre. At least some of the shorter segments, such as those between 9:30 and 10:00, must have originated from the WLS studios. Finally, the National Barn Dance identity also encompassed the active program of artist tours and personal appearances managed through WLS Artists, Inc. For example, the Des Plaines Theater, in the Chicago suburb of the same name, hosted the "WLS National Barn Dance Gang" in 1931 and a "WLS National Barndance" stage show in 1935. The latter featured Rube Tronson and His Texas Cowboys, Arkansas Woodchopper, Tom Corwine, Bob Gardner, and the Hayloft Trio. 87

Such size and scope of the National Barn Dance in the 1930s necessitated a prodigious outlay of management and support services. For instance, a radio column in an Atlanta newspaper noted that because each week's program comprised around twenty musical numbers, and because an effort was made to avoid repetition, the WLS music librarian had the monumental task of supplying over a thousand pieces each year. These numbers, however, reflect only the network portion of the broadcast, so the total number of songs and tunes needed was at least four times greater. However, the repetition of songs favored by the audience was, in fact, not avoided, and was carefully monitored through fan mail sent to the station. Esther Mowery of Decatur, Indiana, recalled how as a teenaged fan of Patsy Montana, she kept a notebook by the radio, and each week was able to write down more of the lyrics of Montana's big hit "I Want to Be a Cowboy's Sweetheart." After she had learned the complete song, Esther performed it with a band of her siblings, including fiddler Francis Geels, at a circa 1937 WLS Home Talent Show somewhere in northeastern Indiana. 88

Besides requiring a large repertoire of songs, the four-and-a-half hours of Barn Dance air time–along with the stage show and the constant demand for personal appearances–presented WLS with a continual need to replenish its talent. The Old Hayloft had its stars, of course, a number of whom stayed at the station for decades. But the show also needed a constant supply of fresh faces and voices, with skills that meshed with the rest of the cast and the spirit of the endeavor. Edgar Bill, Glenn Snyder, George Biggar, and John Lair were some of the WLS executives responsible for locating and auditioning performers and, further, for fitting them into the ongoing operation of the programs. Biggar's memoir provides perhaps the best description of how the many parts fit together:

The National Barn Dance from the stage of the Eighth Street Theatre was primarily divided into half-hour programs–each unit period being built around a "star" with about three other acts–singles, team, trio or instrumental-vocal unit. Each program, usually sponsored, was carefully routined [sic] in advance to insure proper pacing. During a typical evening, about twenty entertainment units–singles or larger–appeared during the evening–for a total of between forty and fifty people. There were always two sets of square dancers of eight members each, with callers.

Future Country Music Hall of Fame member Bill Monroe, for example, got his professional start in show business as an NBD square dancer shortly after he moved north from Rosine, Kentucky, to join his brothers working at an oil refinery in northwest Indiana. Other promising young performers, as Biggar noted, hit the big time of being hired by WLS after a final audition before the audiences at the Eighth Street Theatre. Such was the experience of the Flannery Sisters, who were heard by the Girls of the Golden West (Dolly and Milly Good), when they played a barn dance road show in the Flannery's home town of Gladstone, Michigan, in 1935. At Dolly and Milly's recommendation, the Flannery Sisters were invited to Chicago for an audition, and a week later they were touring the Midwest and appearing on the Saturday night Barn Dance. 89

While perusing the photographs published in the annual WLS Family Albums, it is easy to be struck by the youth of so many of the Barn Dance musicians. Yet even many of the youngest were already experienced radio performers when they came to WLS. The Three Little Maids, Smiley Burnette, and Pepper Hawthorne all came from an important downstate Illinois rural-oriented station, WDZ, in Tuscola. Pepper, a native of Ramsey, Illinois, and a veteran of a WLS Home Talent Show in nearby Decatur, was just eighteen in 1941 when she joined WLS–her third station! 90 Many of these young artists matured artistically during their tenure in the Old Hayloft, and when they left found continued success in the entertainment industry. It is worth noting that a phenomenal number of marriages took place among cast members or between performers and members of the support staff. The number of such marriages reflects the fact that the National Barn Dance was singular in the field of country music for its concentration of featured female artists. 91

A careful examination of the music of the National Barn Dance, within the larger context of the developing professionalization of country music during the 1930s, reveals other distinctive aspects of the sounds that rang throughout the Old Hayloft. In one area, the Barn Dance stands practically alone: the pervasive popularity of yodeling. A large number of NBD stars wove solo and harmony yodels into many of their performances. The Arkansas Woodchopper was probably the first Barn Dance artist regularly to incorporate a yodel. Gene Autry also was an early yodeler in the Old Hayloft, but Autry's yodels reflected the bluesier style of Jimmie Rodgers, America's famous "Blue Yodeler." Most subsequent yodeling on the Barn Dance was of a western flavor, and some even contained small traces of Alpine sounds. Solo yodelers included the station's "little Swiss miss" Christine [Endeback], Pie Plant Pete, Red Foley, and the most famous, Patsy Montana. But NBD audiences also often heard team yodels, in a call-and-response pattern, from Lulu Belle & Scotty, and close harmony yodels from the Girls of the Golden West and the DeZurik Sisters. 92

Will There Be Any Yodeling in Heaven? by Girls of the Golden West, 1934

Ti Yippi Ty Ee by Overstake Sisters (aka Three Little Maids), circa 1935