The Rise of Rural Rhythm

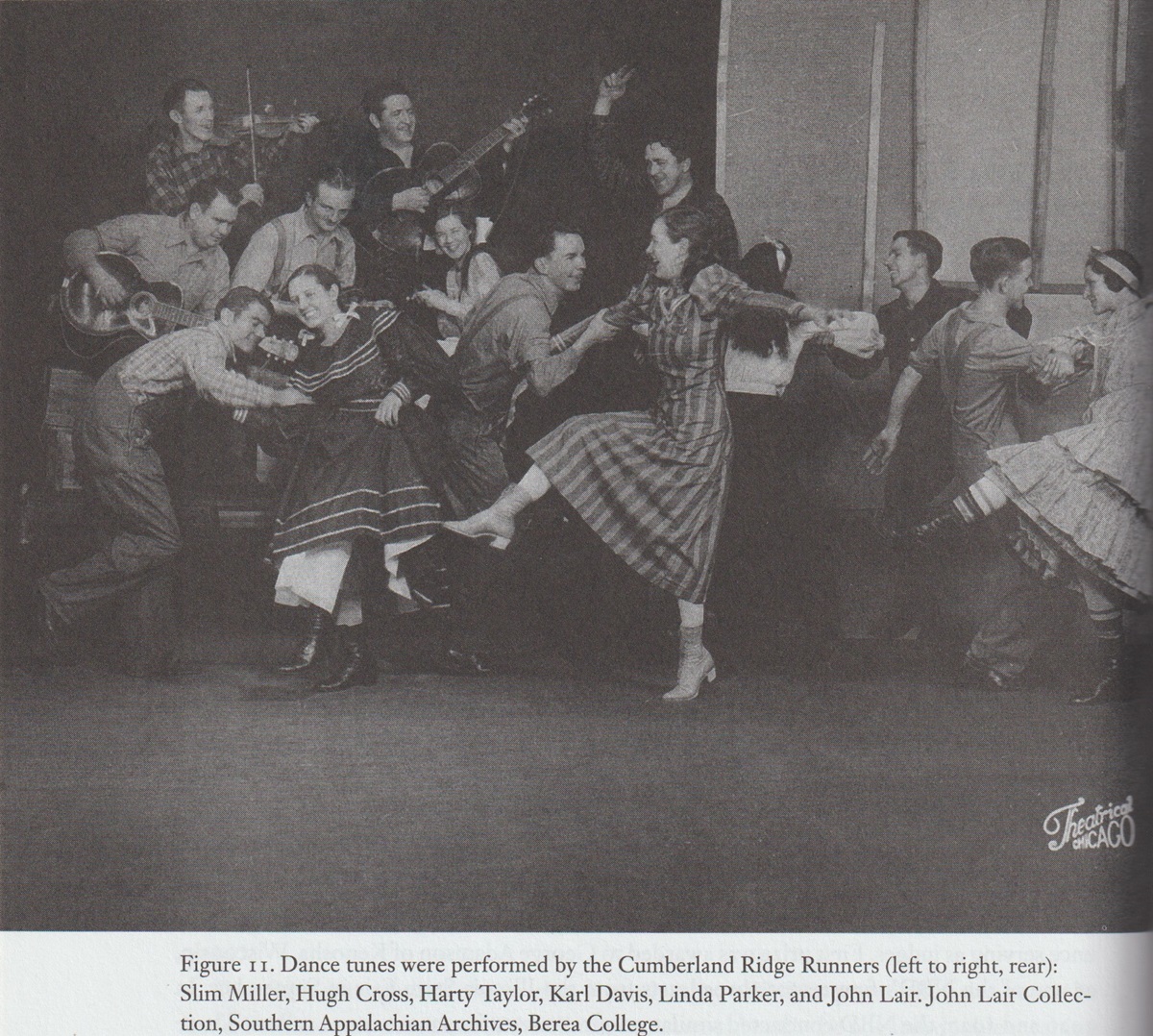

The Hayloft Gang: The Story of the National Barn Dance

By Paul L. Tyler. University of Illinois

Press, 2008, pp 19-71.

With audio annotations. Part 1, pp. 19-37 - Go to

Part

2, pp. 37-71

“I’ve heard the barn dance fiddlers,

I’ve heard the square dance call.”

–from “Cowboy

Rhythm” by Patsy Montana

On a Saturday in the spring of 1924–April 19th, to be exact–if you turned to a middle section of your newspaper–perhaps the Chicago Herald and Examiner–you might have spotted a short article titled “National Barn Dance Tonight.” The announced barn dance was not a soiree scheduled for some farmer’s outbuilding in a rural district somewhere outside Chicago’s city limits. It was, in fact, intended for a nationwide audience that could listen in as an unnamed old- time fiddle band sawed out square dance tunes in a studio recently constructed in the Hotel Sherman in the heart of Chicago. Attendance at this first National Barn Dance would be through a headset or a primitive speaker connected to a radio tuned into WLS, the newest station vying for attention in the bustling airwaves of America’s second largest city. Any dancing would have to take place in the listener’s parlor or kitchen, in close proximity to that newfangled radio set.

WLS’s National Barn Dance was not the first radio program to feature old-time fiddlers. Local masters had already fiddled on stations in Iowa, Atlanta, and Columbus, Ohio. Other significant early radio appearances by fiddlers occurred in Texas. In December of 1922, WFAA in Dallas offered a concert by “Colonel William Hopkins, fiddler of Kansas City.” Col. Hopkins, a 45-year veteran of the fiddle and bow, was accompanied by pianist Charles Krause on such numbers as "Old Southern Melodies," "Arkansas Traveler," and "Bows of Oak Hill” (the latter tune was recorded five years later by the National Barn Dance’s Tommy Dandurand under the more usual spelling, “The Beau of Oak Hill”). A month later, in nearby Fort Worth, WBAP aired a show of square dance music that featured the fiddling of Capt. Moses J. Bonner, a Confederate veteran, and Fred Wagner’s Hawaiian Five Hilo Orchestra. Spurred on by the enthusiastic response from a widely-scattered audience, WBAP broadcast old-time fiddlers several times a month on an irregular schedule over the next few years. 1

When the WLS National Barn Dance went on the air in April of 1924–in the station’s second week of operations–it was perhaps intentionally following trails blazed by the Texas stations or, closer to home, by KFNF in Shenandoah, Iowa. Most country music historians regard WBAP as the originator of the radio barn dance format, yet it is not clear that WLS borrowed either the format or the barn dance name from the Fort Worth station. But someone in Chicago must have been listening, for by the second week of the National Barn Dance, the local papers listed an appearance on the program by Cowbell Pete. According to WBAP’s official history, the Fort Worth station was the first to use an audible logo, a cowbell, introduced in 1922. At WLS, cowbells became a signature sound accompanying applause through at least the first two decades of the National Barn Dance. 2

Opening Theme National Barn Dance network segment, 1939

Jake & Lena routine by Gene & Glenn National Barn Dance network segment, 1938 [?]

Though it may not lay claim to having been the first radio barn dance, the WLS show soon became a dominant feature of the Saturday radio lineup in Chicago, the Midwest, and across the country. As it evolved, the National Barn Dance proved to be incredibly durable, missing only one or two Saturday nights over the next thirty-six years. As will be shown, it also became immensely popular and extremely influential. But in those early years of radio, when programming everywhere was intermittently scheduled–some cities following Chicago’s lead in having “silent nights”–the National Barn Dance was still something of an experiment. WLS’s first station manager, Edgar Bill, described how it came about:

The truth is that it just grew up and here is how it happened. We started WLS with a large variety of entertainment programs. We would try anything once to see what our listeners thought of it. We had religious programs and services on Sunday. We featured high-brow music on one night; dance bands on another; then programs featuring large choruses. Other nights, we'd have variety or we might have a radio play. When it came to Saturday night, it was quite natural to book in old-time music, including old-time fiddling, banjo and guitar music and cowboy songs. We leaned toward the homey, old-time familiar tunes because we were a farm station primarily [emphasis added].

The Saturday night mix struck a chord with the target audience. According to the Chicago Evening Post, within the show’s first few weeks “more than a thousand letters have come in from twenty states expressing appreciation of the old-fashioned barn-dance music.” Letters came from a variety of listeners young and old, and several quoted in the article were written by folks living within the city limits of Chicago. Because much of Chicago’s population was newly arrived from rural districts, WLS’s farm-oriented programming became the favorite of many city residents as well. 3

This distinctive pairing of a strong, rurally targeted radio station with a potent institutional base in a major metropolis explains much about how WLS and the National Barn Dance, in the years before World War II, came to be the preeminent radio home for what would later be called Country Music. In the crowded field of radio broadcasting in Chicago, WLS offered up programming no other Chicago station had in hopes of attracting an audience that was mostly ignored by its competitors. The other half of this powerful combination was the organizational entity behind the radio station. WLS was owned successively by two large and successful corporations that provided resources sufficient to make the National Barn Dance easily the largest show of its kind before 1942.

Yet, though the National Barn Dance was a towering presence in the emerging commercial field of Country Music in the second quarter of the Twentieth Century, the last echoes of those early Barn Dance fiddlers have long since died away. A substantial paper trail tells us who the stars were, and demonstrates that an extensive audience eagerly tuned in weekly to the broadcasts, traveled to Chicago and other Midwestern towns to attend live shows, and snatched up souvenir songbooks and photo-filled yearbooks. The actual sounds of the National Barn Dance, however, have long been missing from our public consciousness. The artists broadcast live, and recording technology was not regularly employed to capture for posterity the sounds they sent out over the airwaves. A few incomplete aircheck disks have been turned up from the show’s second decade, but the playing and singing, the comedy and banter that came into listeners’s homes through those early radio sets can only be imagined. Before turning our focus to the main topic of this essay, reconstructing the music of the National Barn Dance, it would be worthwhile to recap the institutional history of WLS’s landmark program.

Growth of the National Barn Dance

Through its first four years, WLS was operated by Sears, Roebuck and Company, a Chicago-based retailer that relied heavily on mail-order catalog sales. The station's call letters stood for "World's Largest Store." More accurately, WLS was the responsibility of Sears's Agricultural Foundation, chartered in 1923 to help farmers "farm better, sell better, and live better." 4 Of course, if farmers were successful at the first two of these items, they would have more disposable income to spend on the last; and if Sears demonstrated acceptable ideals about what living better meant, and offered desirable products, a portion of that disposable income would lead to increased sales of Sears merchandise.

By 1928, because WLS had not yet turned a profit, Sears sold its station to The Prairie Farmer magazine. At the time, the cast of the National Barn Dance (hereafter also referred to as NBD or by the show's nickname, the Old Hayloft) included nearly thirty performers. By the middle of the next decade, even so large a cast was dwarfed by the numbers that appeared on Saturday nights: between seventy and one hundred instrumentalists, vocalists, singers, comedians, and other variety artists. 5 It is important to note that from early on, at least some NBD stars also appeared on other WLS programs throughout the week. In addition, other WLS artists, whose primary responsibilities were on weekday programs, joined the Hayloft Gang on Saturday nights as well.

The Prairie Farmer, founded in 1841, was a bi-weekly publication with a mission that meshed well with that of Sears's Agricultural Foundation, especially after Burridge D. Butler, a conservative crusader for agriculture, became the magazine's publisher in 1909. Under Butler's direction, the magazine provided farmers with a steady stream of information about issues facing agriculture and sought to serve by bringing them the best advantages of modernization without endangering the traditional values and meaningful symbols of agrarian culture. The Prairie Farmer rose from the pack of nearly fifty farm-oriented journals published in Chicago and Illinois to be the leading agricultural publication in the region, if not the nation. Reflecting Butler's idealistic stance, on the occasion of WLS's ninth birthday, the magazine declared that "America's oldest farm paper considers it almost a sacred privilege to serve as custodian of this powerful 50,000-watt station, acknowledged everywhere as the broadcaster with the greatest audience of the common, everyday folks on farms and in towns and cities." 6

What Sears had started yielded an amazing harvest under Butler's Prairie Farmer. Always a careful businessman, before purchasing WLS, Butler sent sixty "field men" out for six weeks to discover the radio preferences of over 16,000 midwestern farm families. Their findings, that WLS clearly stood alone at the top of the list, sealed the deal. After eight years as the Prairie Farmer station, WLS set a record for the largest mail count received by a station in the country: "more than one million letters in the first six months" of 1936. Combined with increased advertising potential and growing profitability, WLS proved one of Butler's guiding principles, that "service had its rewards." 7

Stuffed mailbags and many listener surveys all attested to the fact that the National Barn Dance was the jewel in the crown of Butler's media empire. Several important steps were taken in the next few years that assured the continuing prominence of the Barn Dance. In 1931, WLS became a 50,000-watt powerhouse, covering most of central North America. In 1932, due to popular demand for passes to see the show live in the broadcast studio, the station moved the NBD to the Eighth Street Theatre, where they sold out two two-hour shows every Saturday night–starting at 7:30 and 10:00–from March 19, 1932, to August 31, 1957. And then starting in August of 1933, a one-hour segment was broadcast coast-to-coast on the NBC-Blue network. Miles Laboratories, of Elkhart, Indiana, sponsored the network segment in order to promote a new product, Alka-Seltzer. 8

Other National Barn Dance segments continued broadcasting on the WLS airwaves through the support of a variety of sponsors. A typical Saturday night program lineup in the 1930s looked like this listing from 1933:

- 7:30 National Barn Dance.

- 8:00 "Big Yank" Variety Program

- 8:15 Aladdin Program – Hugh Aspinwall 10/28

- 8:30 Keystone Barn Dance Party.

- 9:00 Kitchen Klenzer–Three Kings–WLS Trio

- 9:15 Mac and Bob

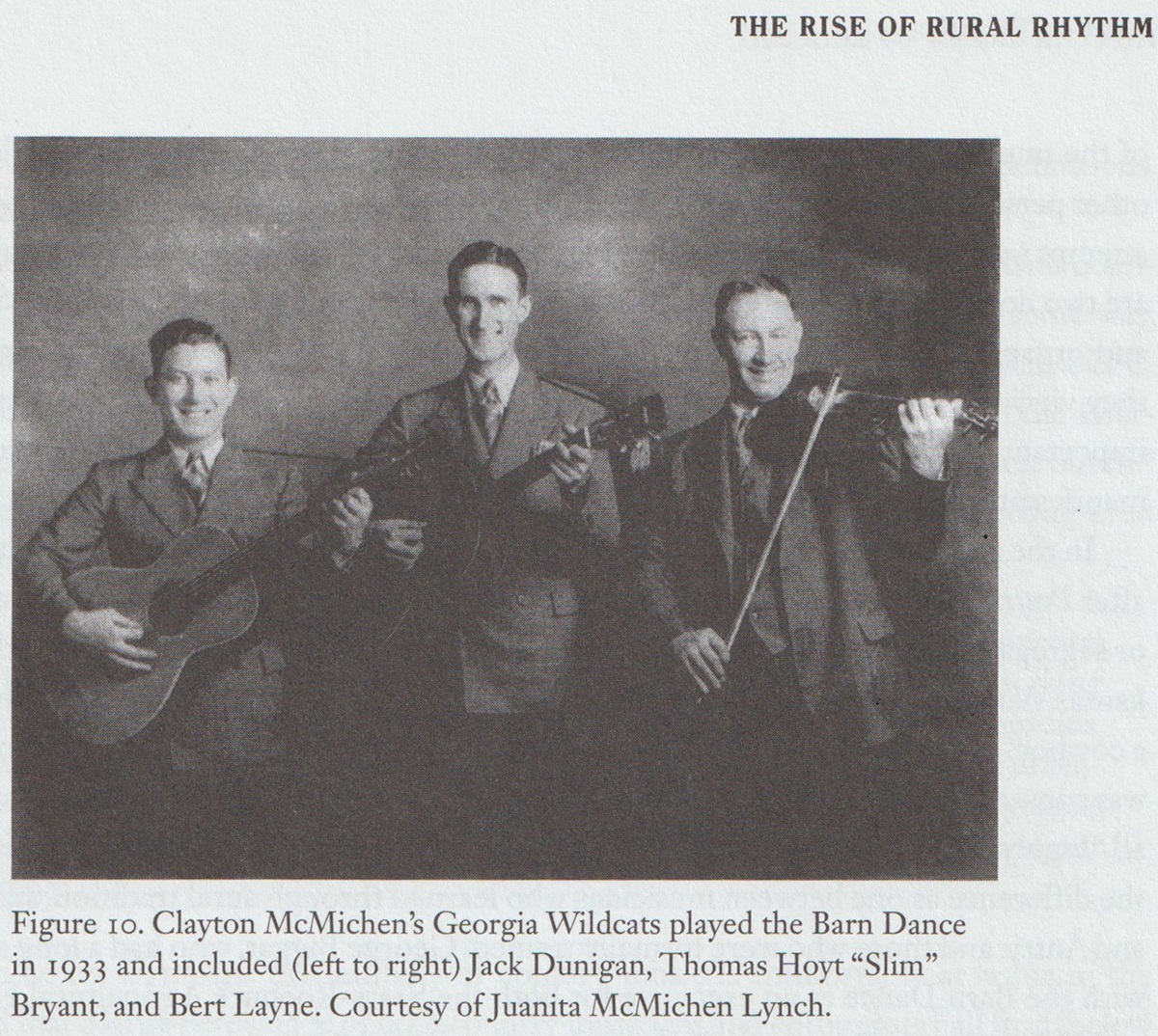

- 9:30 Cumberland Ridge Runners

- 9:45 Song Story by the Emersons. (Geppert Studios)

- 10:00 National Barn Dance (NBC Network for Alka-Seltzer)

- 11:00 Prairie Farmer Barn Dance.

- to 12:00 9

I Told the Stars About You by Mac & Bob, 1933

Sally's Not the Same Old Sally by the Cumberland Ridge Runners, 1933

The mix of sponsors reveals the surprising breadth of the audience for the Barn Dance. A producer of work shirts sponsored the Big Yank program, while Keystone Steel and Wire Company of Peoria, Illinois, sponsored the long-running Keystone segment. The products of the two companies were presumably useful both to farmers and those engaged in industry. The Aladdin Mantle Lamp Company, on the other hand, manufactured kerosene and oil burning lamps that would have been particularly relevant to farmers and other residents of areas not yet reached by rural electrification projects. Time and again, especially during the Butler years, WLS proved to be remarkably effective at building connections with its audience. By at least 1930, the National Barn Dance was being broadcast in front of large live audiences at the Illinois and Indiana State Fairs in what became annual appearances. Early in the Prairie Farmer era, WLS Artists, Inc., was formed to book live performances of road shows. One purpose of this venture was to help staff musicians–not all of whom were full time–supplement their incomes, but another reason was undoubtedly to help meet the demand voiced by the station's listeners. In 1933, the station also began to promote "Home Talent Shows," in which listeners–usually kids–could imitate their favorite WLS performers on stage and also be entertained by real stars from the Old Hayloft.

For three years, starting in February 1935, WLS published a weekly fan magazine that started out as Prairie Farmer's WLS Weekly and was soon changed, after a naming contest, to Stand By! The sixteen-page, large-format magazine contained photographs and features on NBD artists and other WLS personalities, a full broadcast and live appearance schedule, letters from listeners, and several news and queries columns. The longest-lasting artifacts of these relationship-building activities are the WLS Family Albums, published annually beginning in November of 1929 for the following year, with the last one appearing in 1957. 10 These slickly produced, forty to forty-eight paged books crammed with photographs and homey introductions to all of the station's on-air staff can still be found at midwestern flea markets and antique stores.

Several landmark occasions demonstrate the incredible popularity of the National Barn Dance throughout the 1930s. In the fall of 1930 two performances were scheduled for the large International Amphitheatre located at Chicago's famous stock yards. Ten thousand people were able to attend each show. According to reports, an equal number were turned away from the first show. The crowds were even bigger–20,000 per night–for the NBD's one-night-per-week appearance during September 1933 at the Century of Progress Exposition, better known as the Chicago World's Fair. Perhaps the most stunning was the occasion in July of 1939 when 60,000 people from fifteen different states somehow crowded into a public park in the small town of Noblesville, Indiana, for a Sunday picnic featuring WLS's Little Brown Church of the Air. Though some churches had canceled services so their parishioners could attend, the real draw was Barn Dance stars Patsy Montana, the Maple City Four, the Hoosier Sodbusters, and comedian Little Genevieve. Patsy Montana remembered singing in front of those 60,000 fans as a "staggering experience. . . . These were farmers, working hard to make their chores work out so they could drive a great distance and still get home in time for evening chores."11

Swing Time Cowgirl by Patsy Montana, 1940

Understanding the Music of the Old Hayloft

What was it about the music of the National Barn Dance that so endeared it to huge numbers of rural and urban midwesterners? My attempt to reconstruct the nearly forgotten sound of the NBD's early years, will start with how a WLS publicist framed the very first program of barn dance fiddlers. A glimpse of the show's future appeal shines through in the "National Barn Dance Tonight" article mentioned at the beginning of this essay. Here is the text in full:

"All hands 'round—swing your

partner—sasahay [sic] 'round—do, si, do—balance partners!" The old

familiar calls of the barn dance fiddler will

reverberate from many a concrete barn tonight, when Sears Roebuck

Station W L S conducts its first weekly national barn dance over the

radio.

Farmers the country over, heeding the

announcement of the Sears-Roebuck Agricultural Foundation, have

planned barn dance parties for this evening. Young and old will have

their fling from 8 p.m. till midnight, because Isham Jones' College

Inn Orchestra will alternate with the fiddlers and other musicians

of yesteryear. This will be the only W L S program on the air today.

12

Hell on the Wabash called and played by Tom Owen's Barn Dance Trio, 1926

This short text signifies a great deal about the substance and style of WLS's attempts to serve the rural community. Living better, in the view of Sears and, later, the Prairie Farmer, involves such decidedly non-material values as community and sociability, reaching out across generational divides, and respect for the old blended with an openness for the new. WLS could benefit farmers' lives by providing them, in addition to timely information and educational features, the kinds of entertainment preferred by farm folk. The Sears catalog, of course, offered for sale many material accessories related to this vision for living better, including radio sets, phonograph records, and musical instruments. And Sears continued to use WLS and the Prairie Farmer to advertise its catalog and merchandise.

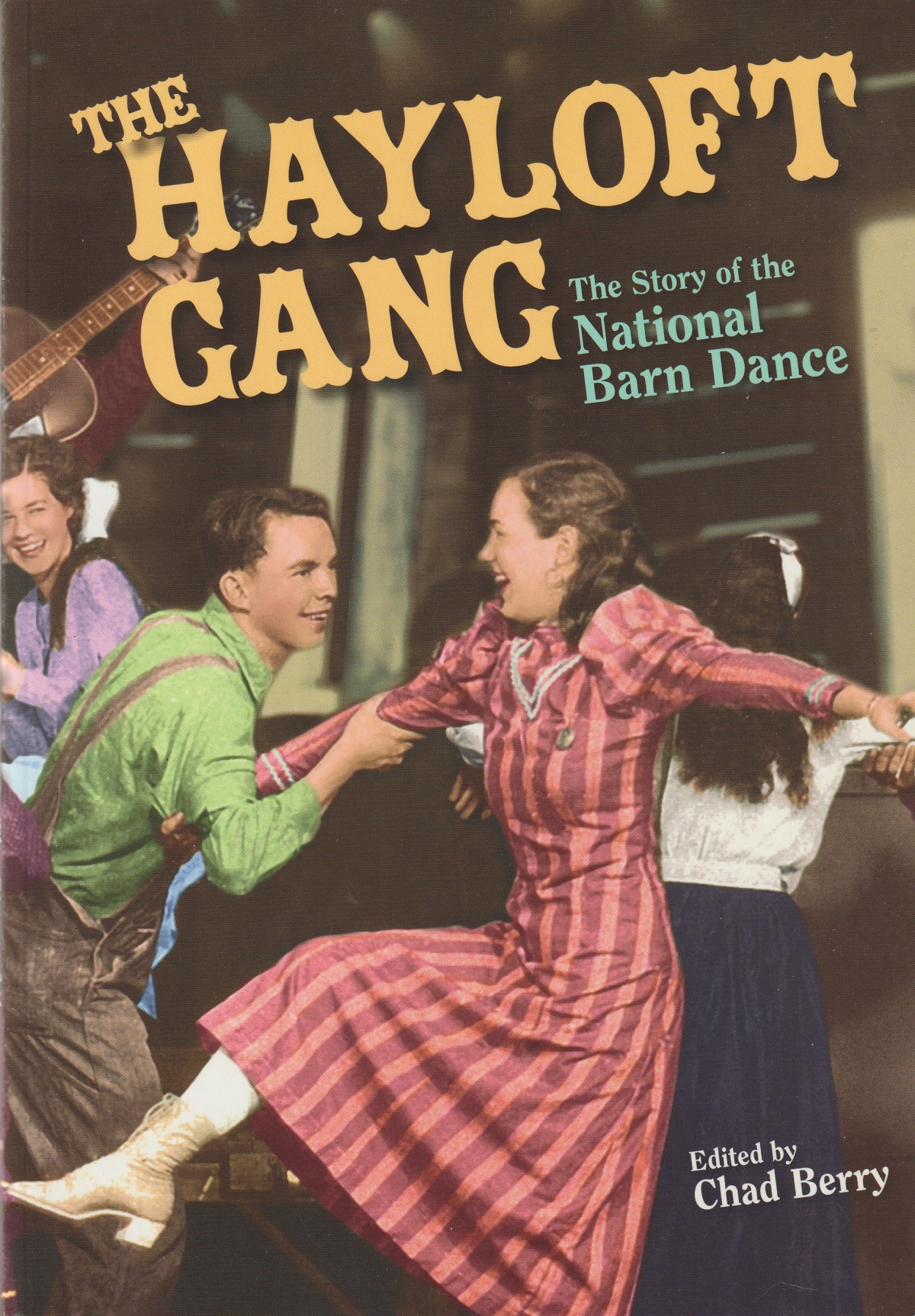

Unfortunately, although the full introductory

announcement printed in the Chicago Herald & Examiner

suggests so much, it did not appear in any other of Chicago's

half-dozen daily newspapers. The first post-World War II generation

of country music historians all missed the story, which has led to

several misunderstandings about the nature of the Barn Dance. For

instance, from a local radio host and a NBD memorabilia collector, I

have heard recent retellings of the myth of the Barn Dance's

accidental beginnings. The contemporary spread of this narrative

dates to 1966 when Robert Shelton, popular music critic for the New

York Times, published The Country Music Story. Shelton's

source was probably John Lair, an important WLS programmer during

the 1930s. The myth went as follows: Saturday night arrived and

"‘there was just nobody to put on the air.' The station manager was

in Evanston, and Tommy Dandurand, a janitor at the station, brought

out a scratchy fiddle and somebody got a cowbell, and off it went."

13 From the Chicago Herald &

Examiner notice, it is patently clear that WLS executives

were more careful in their planning, and the show was no accident.

And although Tommy Dandurand is often named as the first fiddler on

the Barn Dance, it is doubtful he was a janitor for the station or

the Hotel Sherman. Dandurand had been a streetcar motorman in

Kankakee, Illinois, and had moved to Chicago to live with his son

after losing a leg in an automobile accident two years earlier. 14

Unfortunately, although the full introductory

announcement printed in the Chicago Herald & Examiner

suggests so much, it did not appear in any other of Chicago's

half-dozen daily newspapers. The first post-World War II generation

of country music historians all missed the story, which has led to

several misunderstandings about the nature of the Barn Dance. For

instance, from a local radio host and a NBD memorabilia collector, I

have heard recent retellings of the myth of the Barn Dance's

accidental beginnings. The contemporary spread of this narrative

dates to 1966 when Robert Shelton, popular music critic for the New

York Times, published The Country Music Story. Shelton's

source was probably John Lair, an important WLS programmer during

the 1930s. The myth went as follows: Saturday night arrived and

"‘there was just nobody to put on the air.' The station manager was

in Evanston, and Tommy Dandurand, a janitor at the station, brought

out a scratchy fiddle and somebody got a cowbell, and off it went."

13 From the Chicago Herald &

Examiner notice, it is patently clear that WLS executives

were more careful in their planning, and the show was no accident.

And although Tommy Dandurand is often named as the first fiddler on

the Barn Dance, it is doubtful he was a janitor for the station or

the Hotel Sherman. Dandurand had been a streetcar motorman in

Kankakee, Illinois, and had moved to Chicago to live with his son

after losing a leg in an automobile accident two years earlier. 14

Another confusion surrounds the name of the program, which was dubbed the National Barn Dance at its very beginning. As estimable a scholar as Wayne Daniel has mistakenly claimed that the NBD was known initially as the "WLS Barn Dance," and that "National" was added to the name when the NBC Blue network picked up a segment of the program in 1933. Daniel is justified in the first half of his assertion by the casual way in which the program was named in radio program listings published daily in the papers. Often the show was simply called the "Barn Dance" or the "WLS Barn Dance." Through the summer of 1924, WLS's Saturday night program listings included a variety of names, such as "Old time fiddlers program," "National farm barn dance," and "Barn dance fiddlers." For a time in the fall of that year, it appears that WLS might have been trying to shift the program's focus away from the image of the barn dance, and titles like "Saturday night Mardi Gras" and "WLS review night" become more prominent. But by the dawn of 1925, Saturday night at WLS was given back over to a "national barn dance" or to simply a "barn dance." 15

Finally, the Chicago Herald and Examiner announcement heralding the first National Barn Dance reveals clearly an essential characteristic of the early programs, a trait that would carry over for the next thirty-six years (the first half of which are covered by this essay). The music of the Barn Dance, and of WLS weekday programs, comprised a very broad range of styles and genres. On that first program, the old-time fiddlers (or fiddle band) alternated with a modern ballroom orchestra, and every Barn Dance program that followed included both pop and country artists–or to use a music industry term from before 1950, "hillbilly" musicians. This basic fact has proved problematic to most postwar country music scholars, and has led, at minimum, to the NBD's importance being understated and, at worst, to it being misrepresented in scholarly writings on country music.

Wayne Daniel summed up the contemporary heuristic problem succinctly in his opening salvo for the Journal of Country Music in 1983: "Drawing from standard country music reference works and WLS publications, several writers have agreed that the National Barn Dance delivered to its audiences 'a mixed musical array' that was 'decidedly more "popular" than "hillbilly."' New evidence to support this conclusion is put forth in this article." 16

Sadly, the consensus that the WLS Barn Dance lacked a certain degree of country or hillbilly authenticity has consigned the NBD to virtual footnote status in the standard country music reference works. Cursory treatments of the show highlight the fact that Country Music Hall of Fame members Gene Autry and Red Foley started out on WLS, and do little more than list the names of other key performers. And most histories of country music go little beyond the cursory when discussing the National Barn Dance. Though some recently published and online reference works contain solid entries on key Barn Dance performers, little has been done to integrate their contributions into larger historical narratives. Ivan Tribe's entry in the on-line Century of Country reveals an irony that explains why the NBD has been regularly overlooked in so many quarters: "Overall, it is quite difficult to overestimate the importance that the National Barn Dance played in the growth of Country music on radio in the second quarter of the 20th century. Sadly, no anthologies of the music of performers from that era have ever been released." The music of the Old Hayloft has been roundly ignored, so it is no surprise that a recently-published encyclopedia of Chicago history, besides getting the show's name wrong, characterizes the NBD as "nearly forgotten today." 17

The Barn Dance is not well-remembered primarily because of the incompleteness of the sonic record. By the time I wrote this essay, I had identified only eight or nine preserved air-check recordings of the Barn Dance from before 1945. Most were recorded during the war years, with only a single program from 1939 surviving from the time period covered by this essay. Apparently all the surviving air-checks from the early years are of the sixty-minute long NBC network segments. Thus only a selective portion of the entire program has been preserved. The National Barn Dance encompassed at least five hours each week, and presented numerous artists who were seldom or never featured on the network segment sponsored by Alka-Seltzer! Fortunately, many NBD artists did leave behind a large body of work of commercial phonograph records. However, very few of these recordings are currently available through record company catalogs. While many rare pre-WWII recordings of rural musicians have been reissued in LP and CD formats over the last four decades, NBD artists have not been fairly represented.

This dearth of National Barn Dance artists on contemporary reissue recordings is both a symptom and a cause of our contemporary amnesia about one of radio's most storied programs. Consider the case of the biggest NBD stars: Lulu Belle & Scotty, Arkie the Arkansas Woodchopper, and the Prairie Ramblers. In an audience poll conducted in 1937, WLS listeners voted these three the most popular acts on the station. All three are noteworthy for their longevity with WLS. Lulu Belle & Scotty joined the Barn Dance cast separately in the mid-1930s and, except for a two-year hiatus, performed as a favorite NBD duo until their retirement in 1958. The Arkansas Woodchopper had a even longer run, coming to WLS in 1929 and staying with the Barn Dance even after it left WLS in 1960 and moved to WGN. The Prairie Ramblers were also associated with the NBD through the better part of three decades, from 1933 through about 1956, with several short periods off to work at other stations. But only two albums on American record labels were ever devoted to reissues of earlier 78rpm recordings by these artists: i.e., Lulu Belle & Scotty, Early and Great, Vol. 1 on Old Homestead Records, and Patsy Montana & the Prairie Ramblers on a Columbia Historic Edition LP. Recently, the first-ever reissue of the Arkansas Woodchopper's early recordings appeared on the small independent label, British Archives of Country Music.

Get Along Home Cindy by Lulu Belle & Scotty, 1935

A Hard Luck Guy by Arkansas Woodchopper, 1930

You Look Pretty in an Evening Gown by the Prairie Ramblers, 1935

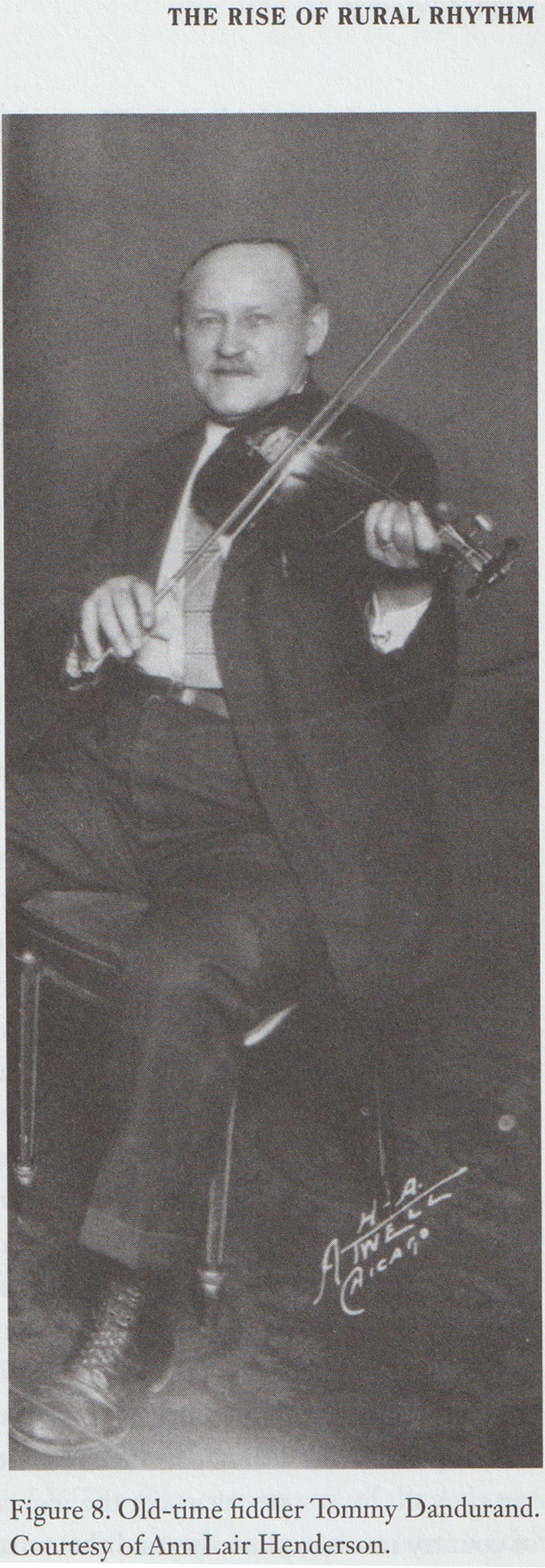

This lack of representation on post-World War

II commercial recordings is even more puzzling when one discovers

how prolifically Old Hayloft musicians recorded during the period

covered by this article. The Prairie Ramblers, for instance,

recorded 257 pieces between 1933 and 1942, while also accompanying

singer Patsy Montana on an additional eighty-seven sides. Another

measure of their recording activity comes from their sixth-place

standing on a list of country artists with the greatest number of

recording sessions–the Ramblers and Patsy made seventy-five visits

to the studio. This list, which I compiled from an analysis of the

data compiled in Tony Russell's valuable Country Music Records:

A Discography, 1921-42, contains several other Old Hayloft

artists. With 115 recording sessions, Gene Autry

has a clear hold on third place, while fiddler Clayton

McMichen, who recorded with his own George Wildcats as

well as with Gid Tanner & the Skillet Lickers is in tenth, but

would move higher if the Skillet Lickers sessions were factored in.

Mac & Bob, with fifty-three sessions, are

ranked eleventh, while the Hoosier Hot Shots, with thirty-nine,

finish off the top twenty. It should be noted that some critics

regard as suspect the "hillbilly" credentials of four of the artists

at the very top of this list–Vernon Dalhart, Carson Robison, Frankie

Marvin, and Bob Miller. If this is the case (and I am not

comfortable with the argument), then the two most

frequently-recorded authentic rural or country musicians up through

1942 are National Barn Dance stars Gene Autry and the Prairie

Ramblers. 18

This lack of representation on post-World War

II commercial recordings is even more puzzling when one discovers

how prolifically Old Hayloft musicians recorded during the period

covered by this article. The Prairie Ramblers, for instance,

recorded 257 pieces between 1933 and 1942, while also accompanying

singer Patsy Montana on an additional eighty-seven sides. Another

measure of their recording activity comes from their sixth-place

standing on a list of country artists with the greatest number of

recording sessions–the Ramblers and Patsy made seventy-five visits

to the studio. This list, which I compiled from an analysis of the

data compiled in Tony Russell's valuable Country Music Records:

A Discography, 1921-42, contains several other Old Hayloft

artists. With 115 recording sessions, Gene Autry

has a clear hold on third place, while fiddler Clayton

McMichen, who recorded with his own George Wildcats as

well as with Gid Tanner & the Skillet Lickers is in tenth, but

would move higher if the Skillet Lickers sessions were factored in.

Mac & Bob, with fifty-three sessions, are

ranked eleventh, while the Hoosier Hot Shots, with thirty-nine,

finish off the top twenty. It should be noted that some critics

regard as suspect the "hillbilly" credentials of four of the artists

at the very top of this list–Vernon Dalhart, Carson Robison, Frankie

Marvin, and Bob Miller. If this is the case (and I am not

comfortable with the argument), then the two most

frequently-recorded authentic rural or country musicians up through

1942 are National Barn Dance stars Gene Autry and the Prairie

Ramblers. 18

Methodist Pie by Gene Autry, 1931

Bummin On The I. C. Line by Clayton McMichen's Georgia Wildcats, 1932

Bright Sherman Valley by the Mac & Bob, 1927

An

analysis of Russell's discography reveals further hints of the

importance of the National Barn Dance. Of the 1,588 artists that

Russell includes–if their record label marketed them in any way to

white, southern, rural, or small-town consumers, they are included–I

identified fifty-five as having some tenure on the WLS Barn Dance.

According to Russell's own estimate, there were over 28,000 masters

recorded by these nearly 1,600 acts. 19

By my count, at least fifty-five NBD artists recorded 2,333 of these

sides, and that total could be increased by several hundred to make

up for later Gene Autry and Clayton McMichen recordings. In either

case, over 8 per cent of all country music records made between 1921

and 1942 were made by musicians who at one time or another were

members of the Hayloft Gang. Included in these ranks are an

impressive array of musicians–starting with Chubby Parker

and Pie Plant Pete and stretching through the

Cumberland Ridge Runners and the Westerners–who

were undeniably rural in origin and who played and sang in styles

that are today clearly recognized as "Country."

An

analysis of Russell's discography reveals further hints of the

importance of the National Barn Dance. Of the 1,588 artists that

Russell includes–if their record label marketed them in any way to

white, southern, rural, or small-town consumers, they are included–I

identified fifty-five as having some tenure on the WLS Barn Dance.

According to Russell's own estimate, there were over 28,000 masters

recorded by these nearly 1,600 acts. 19

By my count, at least fifty-five NBD artists recorded 2,333 of these

sides, and that total could be increased by several hundred to make

up for later Gene Autry and Clayton McMichen recordings. In either

case, over 8 per cent of all country music records made between 1921

and 1942 were made by musicians who at one time or another were

members of the Hayloft Gang. Included in these ranks are an

impressive array of musicians–starting with Chubby Parker

and Pie Plant Pete and stretching through the

Cumberland Ridge Runners and the Westerners–who

were undeniably rural in origin and who played and sang in styles

that are today clearly recognized as "Country."

I'm a Stern Old Bachelor by Chubby Parker, 1927

When the Work's All Done This Fall by Pie Plant Pete, circa 1945

Ridin' High by the Louise Massey & the Westerners, 1934

Nevertheless, not all of the musicians who performed on the Barn Dance were included in Russell's discography: some because they apparently never recorded, others because their recordings were apparently not marketed for a rural audience. How do we account for the mix of popular and "hillbilly" styles that constituted the NBD? One place to start is by acknowledging that this mix never appeared to be a problem for either WLS or its audience. When the NBD went on the air in 1924, a rubric for defining the difference between country music and pop music did not exist. Through the 1930s, WLS exhibited no desire to limit its audience to narrowly-defined segments of taste or musical preference. And though the station's identifiably rural artists appeared right along such urbane veterans of the music industry as Henry Burr, who had "made more phonograph records than any other person," and Grace Wilson, "the famous ‘Bringing Home the Bacon' girl," no apparent attempt was made to educate the audience about which genre each artist represented. There are two noteworthy exceptions to this rule. Bradley Kincaid and John Lair, a WLS producer and organizer of the Cumberland Ridge Runners, went to great lengths to present what they viewed as authentic folk music from the Southern Appalachians. For both men, it was important to distance their representations of traditional folk song from other commercial manifestations of hillbilly music. 20

In the annual Family Albums that WLS began to publish in 1930, a little more than a year after Prairie Farmer magazine purchased the station from Sears, musical acts are not labeled or segregated by type, beyond small hints or suggestive images. For instance, Arkie the Arkansas Woodchopper had actually chopped wood and Gene Autry had been "really and truly a cowboy" before he became a singer of Western songs. William Vickland, on the other hand, was conservatory-trained, and the Novelodeons, who specialized in comic arrangements, were all "highly skilled musicians." 21 One might infer that WLS and the Prairie Farmer regarded the difference as one between musicians who learned through aural tradition, such as Arkie and Autry, and those who were formally trained. George Biggar, who had a long association with the Barn Dance as an executive for both the Sears Agricultural Foundation and for WLS-Prairie Farmer, applied the descriptive "folk" in a non-academic way in talking about the music of the Barn Dance: "We used the terms ‘folk music' for traditional music, and ‘modern folk music' for more recently written songs." 22 But the WLS programmers were never explicit, and we are left to wonder whether or not they intended the term "folk music" to expand to cover all the music heard on the Barn Dance.

Place of origin was also deemed important by those who wrote copy for the WLS Family Album s and other publications, presumably because it would reinforce connections between the performers and their mostly rural target audience. Thus, the Family Album pointed out that the Three Neighbor Boys "came directly from the farm in Marshall county, Illinois," while the Rock Creek Rangers, a band made up of Sunshine Sue Workman and her brothers, was from a farm in Iowa. Still, farm origins are not enough to characterize or categorize the music styles of these performers. Rural districts in America, especially east of the Mississippi River and even in the Southern Appalachians, were never totally isolated from the movements of people in and out, from visits by itinerant troupes of performers or music teachers, or from the cultural influences of town-based institutions and commerce. Brass bands, church hymnals, and musical instrument salesmen were not limited to the cities. Thus there was no essential or impenetrable divide between the music styles of the metropolis and the countryside. And while traditional fiddling or older ballads and folksongs may have been more commonly found in a rural musician's repertoire, some from the country dabbled in newer sounds, such as band music, ragtime, the latest song compositions from Tin Pan Alley, sophisticated part-singing, or even jazz. In short, some rural musicians, from all parts of the United States, have been known to play music that is, according to current definitions, unmistakably not country music.

But the question of origin raises another problematic issue introduced by postwar country music scholars: that is, the notion that country music is primarily and, in some way, intrinsically, southern. The clearest statement of what I call the southern thesis is in Bill C. Malone's masterful history, Country Music, U.S.A. He began the first edition with the assertion that commercial country music "developed out of the folk culture of the rural South." For the second edition, Malone's definition offered more nuance while reasserting even more strongly the southernness of country music, which

evolved primarily out of the reservoir of folksongs, ballads, dances, and instrumental pieces brought to North America by the Anglo-Celtic immigrants. Gradually absorbing influences from other musical sources, particularly from the culture of Afro-Americans, it eventually emerged as a force strong enough to survive, and even thrive, in an urban-industrial society. . . . It was only in the southern United States, though, that dynamic folk cultural expressions, black and white, evolved into viable commercial forms in our own time. 23

There can be no argument that hillbilly or country music is comfortably at home in the South, and that a large percentage of both country musicians and enthusiasts hail from below the Mason-Dixon line. Similarly, a substantial portion of NBD artists had southern roots, and the program was well-received by southerners who had migrated to Chicago and elsewhere in the Midwest. Yet there is no evidence that regional style was ever the determining factor in selecting or rejecting artists to appear on the Barn Dance, at least before World War II, or in the general preferences of the show's audience.

A few years before Malone's history was published, D. K. Wilgus offered an eloquent description of the multiple roots of what became country music: "Early hillbilly performers came not only from the lowland and upland South, but from the Great Plains and the Midwest . . . . That the first important hillbilly radio show originated in Chicago cannot be explained solely by the presence of Southern migrants. Its manifestation was of the South; its essence was of rural America. Southern hillbilly music seems but a specialized and dominant form of a widespread music." 24 Unfortunately, Wilgus's wisdom has been ignored, and the southern thesis has become gospel truth in the scholarly discourse on country music. Occasionally, scholars have had to make some unwarranted assumptions in order to account for the presence or absence of what they view as real country music, the southern variety, on the National Barn Dance. A few examples will suffice. Jeffrey Lange argued that a group like the Prairie Ramblers, Kentucky natives with a smooth sound and a preference for swing, were necessary on the NBD in the mid-'30s to offset the Cumberland Ridge Runners (also from Kentucky), a more characteristically southern–and presumably rougher-sounding–string band. Following this line of thinking, the Ridge Runners' appeal was limited to the southern migrants in the audiences and, by implication, the Ramblers would not be an appropriate hire for a barn-dance show on a southern radio station. And in an oft-made retrospective comparison with the Grand Ol' Opry on WSM in Nashville, Charles Wolfe described the WLS Barn Dance as "‘soft' country– with a lot of vaudeville, barbershop quartets, polka bands, and ersatz cowboy songs." 25 Wolfe's assertion is correct that such styles were present on the NBD; but the implication that this limited range of styles adequately describes the music of the early National Barn Dance is completely misleading.

Jug Rag by the Prairie Ramblers, 1935

Ole Rattler by the Cumberland Ridge Runners, 1933

Another example of the contortions required to prop up a regional bias stems from a memorable, though regularly misunderstood, statement from a WLS executive. At some point in the early 1950s, long-time station manager Glenn Snyder–he started at WLS in 1932– proposed the term "hungry hillbilly" as the antithesis of what the National Barn Dance was all about. Beginning with Bernard Asbel's 1954 story on the Barn Dance for Chicago Magazine, most critics have asserted that Snyder equated "hungry hillbilly" with southern styles of country music, and "he'll have none of it on WLS." A more careful reading of Asbel's treatment reveals this equation to be rash and unfortunate. According to Snyder's colleague, George Biggar, the "hungry" label referred to the southern-style country bands that played taverns and honky-tonks while costumed in "fancy get-ups," like those fashionable in postwar Nashville. Though this discourse on hungry hillbillies originated in a later period, there is relevance for this essay. Biggar tied the critique of hungry hillbillies to Burridge Butler's commanding preference for a certain style of presentation, for overalls and calico shirts and a mandate that his WLS artists be natural and "ring true." 26 According to practices established in the 1930s, there would be no Nudie suits on the Barn Dance. But Snyder and company never hung out a virtual sign that read "No southerners need apply."

One further tangential observation about hungry hillbillies practically cries out to be made. Perhaps only a resident of the Chicago area would catch the possible double meaning of Snyder's positive term for the music of the Barn Dance: "uptown hillbilly." The tavern district where Snyder's hungry hillbillies plied their trade, as described in Asbel's article, was located on the west side, along Madison Avenue. Uptown, on the other hand, is a north-side neighborhood that has long served as a point of entry for immigrants and, especially in the mid-twentieth century, for white migrants coming to Chicago from the Southern Appalachians and elsewhere in the rural South. Could Snyder's vision of an "uptown hillbilly" have meant a southern mountaineer newly arrived in Chicago; someone whose musical heritage was closer to the mountain folksongs promoted by Bradley Kincaid and John Lair than to artificial hillbilly songs of the music industry? It is worth pondering.

A critique is long overdue of the southern thesis, and of other essentialist explanations of the emergence of commercial country music from the abundance of rural music styles and traditions found throughout America in the first half of the twentieth century. That, however, is beyond the scope of this essay. Let it suffice that when distinctive, commercial, southern forms of country music developed in the 1940s, especially with the ascendancy of Nashville, some of these styles were alien to the goals of WLS and the Prairie Farmer. Still, the dominant southernness of postwar country music should not grant the southern apologists an exclusive claim to the music's historical roots. The dynamic folk traditions of string bands and songsters from the 1920s and into the early 1930s, and the more professionalized soloists, vocal duos, and swing bands of the late '30s were equally developed by rural musicians from the Midwest, the West, and the North.

But if none of the definitions or genre labels offered up thus far by scholars (popular versus hillbilly) or by the NBD's marketing department (folk and modern folk, songs of the mountains and plains) are adequately descriptive, how do we understand the distinctive character of the music of the Old Hayloft? I believe an answer can be found in the merging of the existential dynamics of the radio medium and WLS's reliance on the old and the familiar to win a place for itself in the homes of rural Americans. Once again, the Chicago Herald & Examiner's announcement of the first show provides a clue: WLS's strategy highlighted "the old familiar calls of the barn dance fiddler" and relied on the appeal of pleasurable experiences and nostalgic memories associated with a real barn dance, a widespread institution of communal sociability that many commentators of the time feared was passing from the scene. While the station's executives initially envisioned that rural folks would actually hold a dance on Saturday nights to music supplied from the WLS studios–and some apparently did–it did not take long to realize that this was not the best use of the new medium. 27

Old-time fiddling and square dance calls, nevertheless, continued to be potent symbols for WLS and the National Barn Dance. For four months beginning in the summer of 1924, the station conducted a fiddle contest during Saturday-night broadcasts with the listening audience serving as judges. First prize was awarded to George Adamson of Kenosha, Wisconsin, at one of the NBD's first remote broadcasts from the Illinois State Fair in September. In 1926 and 1927, the NBD conducted similar on-air contests for square dance callers. There were thirty-one contestants in the 1927 contest, but no announcement of who the winners were either year has yet surfaced. 28 Through the 1930s, the Hayloft Gang always included several old-time fiddlers, but by 1939 (the date of the earliest recorded broadcast I have been able to hear), square dance calling had been relegated to a symbolic and transitional role. On the NBC network segment, the Arkansas Woodchopper delivered rapid-fire patter calls that faded out as the program went to a commercial break. A union-mandated, staff orchestra supplied the fiddle breakdown for this network broadcast. 29

Through

their experiments in programming, WLS discovered that the old

familiar music that worked best on radio was music better suited for

the more intimate domestic spaces of the parlor or kitchen, not the

public hall. Old-time fiddling and its associated dance forms

belonged primarily to what folklorists have called "public" or

"assembly" traditions. "Domestic" traditions, on the other hand,

included the customary contexts for the singing of traditional

folksongs and for family music-making. 30

In the latter part of the nineteenth and the beginning of the

twentieth centuries, domestic music traditions increasingly featured

parlor performances made possible with purchases of merchandise from

a music dealer, including sheet music, song folios, and relatively

affordable mass-produced instruments like guitars, mandolins, and

especially the piano. WLS and the Barn Dance found a comfort zone by

concentrating on such domestic traditions, which led to a shift to

smaller and more intimate acts: solo performers, vocal duos and

trios, and jocular conversational skits involving the announcer, as

straight man, and one or two comedians.

Through

their experiments in programming, WLS discovered that the old

familiar music that worked best on radio was music better suited for

the more intimate domestic spaces of the parlor or kitchen, not the

public hall. Old-time fiddling and its associated dance forms

belonged primarily to what folklorists have called "public" or

"assembly" traditions. "Domestic" traditions, on the other hand,

included the customary contexts for the singing of traditional

folksongs and for family music-making. 30

In the latter part of the nineteenth and the beginning of the

twentieth centuries, domestic music traditions increasingly featured

parlor performances made possible with purchases of merchandise from

a music dealer, including sheet music, song folios, and relatively

affordable mass-produced instruments like guitars, mandolins, and

especially the piano. WLS and the Barn Dance found a comfort zone by

concentrating on such domestic traditions, which led to a shift to

smaller and more intimate acts: solo performers, vocal duos and

trios, and jocular conversational skits involving the announcer, as

straight man, and one or two comedians.

Soloists, like Bradley Kincaid and Grace Wilson, and small ensembles, from the Girls of the Golden West to the Maple City Four, all became as familiar as friends to the listeners at home, because they fit well with the dynamics of the new medium. Radio receivers came to be housed in large cabinets, usually crafted as attractive pieces of furniture for a family residence. Audiences listened in the comfort of their living rooms, parlors, or kitchens. In addition, the audio fidelity of radio sets after the mid-1920s far surpassed that of the phonographs of the day. The radio singer's voice was more immediately present in the listener's home than the voice of the phonograph-recording artist. The NBD played up this familiar, homey quality, and asked its performers to be natural, unassuming, and friendly. In constructing their virtual and musical "Old Hayloft," WLS began by modeling it as a public assembly, an old-time social dance in a rustic outbuilding. But they reached their greatest levels of success when they reconfigured the presentation to suggest surroundings as comfortable and as homey as the parlor or living room. The Old Hayloft–the barn that housed the Barn Dance–thus became, not a public venue, but an extension of the home, of the hearth. 31

Gooseberry Pie by Bradley Kincaid, 1930

When the Bees Are in the Hive by the Girls of the Golden West, 1933

Furthermore, the seemingly natural merger between the intimacy of60 radio and the familiarity of old-time songs provided a way for urban popular song artists to fit in seamlessly with the rural musicians of the Barn Dance. Based on the photographic evidence of the WLS Family Albums, at least some of the pop music acts reconfigured their presentation for the domestic setting of the Old Hayloft. A key element for making the transition: the use of one of the countless guitar-strumming members of the station's cast. Slim Bryant, guitarist with Clayton McMichen's Georgia Wildcats, was asked to be the accompanist for one of station's popular songs artists in 1932. On the Barn Dance, the staff pianist–Ralph Whitlock in the 1920s and John Brown during the '30s–may be all the accompaniment a singer used, suggesting a setting like a family parlor. 32

To better understand the import of this reconfiguration, consider that since at least Stephen Foster's era (the decades leading up to the Civil War), the American popular song tradition was centered on public, staged performances. Star singers, who helped the music industry by promoting the latest hits from Tin Pan Alley composers, performed to orchestra accompaniment in concert settings in the popular theater and vaudeville. When the recording industry broke upon the scene, people went to public arcades where they could drop a coin in a cylinder machine and hear a singer backed by a studio orchestra. When the phonograph itself was domesticated, the music on the discs played at home continued to represent the performance practices of the assembly tradition. With the development of radio broadcasting–direct competition for the record industry–popular singers were presented a new venue with its own set of new challenges and demands. WLS and the Barn Dance met those challenges with astounding success by erasing the social distance between the performer and audience, a separation that characterized the assembly tradition. They turned pop singers into friends who had come into your home to visit. 33 Other radio stations, of course, worked similarly successful strategies. The National Barn Dance led the way by using the symbols of rural sociability and old-time music to draw into its embrace music and musicians from more formal and urbane performance contexts. Popular songs could be remade as folk songs, or at least be imbued with the rural values of the Old Hayloft.

The first identifiable pop singers on the National Barn Dance were the duo of Ford & Glenn (Ford Rush and Glenn Rowell), who station manager Edgar Bill discovered in a theater on Chicago's north side during WLS's first few weeks of operation. For the next few years they appeared weekly on the Barn Dance and also hosted a "Lullaby Time" for a half hour prior to the start of the NBD proper. Ford and Glenn were the first in a long line of small vocal ensembles in the Old Hayloft who specialized in close harmony. The list includes such groups as Ingram & Carpenter, the Harmony Girls (1924); Three Hired Men, "Swedish boys with plenty of ‘mean' harmony" (1930); the Milk Maids, including Juanita (Mrs. John) Brown, a native of Adrian, Michigan (1930); Three Neighbor Boys, "their singing has never lost its sweetness and simplicity" (1935); and the Girls' Trio, "three little girls from Des Plaines . . . perfect harmony" (1939). 34 Was the repertoire of these vocal groups country or pop? Such labels apparently did not matter to WLS and its audience. What was important is the easy familiarity with which they brought music into one's parlor. These singers, starring on a nationally prominent radio show, were like . . . well, more like neighbor kids, or hired hands, or other familiar members of your community.

I'll See You in My Dreams by Ford & Glenn, circa 1930

Bringing Home the Bacon by Grace Wilson, circa 1930

Homey and domestic presentations were not the entirety of the National Barn Dance. Many acts still clearly represented the assembly traditions of public performance. These acts ranged from string and swing bands like the Georgia Wildcats and the Westerners to raucous novelty groups like the Four Hired Men and the Hoosier Hot Shots. Also, the Barn Dance always had some sort of staff band. Starting in 1924, it was the generically titled "old time fiddlers." In the early '30s, Rube Tronson's Texas Cowboys–featuring two real country fiddlers along with accordion, clarinet, and other brass–filled that role. In 1932, there was no staff orchestra, and with several organized string bands in the cast, the bands took turns playing for the square dance troupe for its turn on stage. 35 By the end the 1930s, a staff orchestra–with union-card-carrying violinists, not country fiddlers–was on stage for at least the NBC network segment of the broadcast. Network shows from that era started and ended with big production numbers featuring the orchestra and the many-voiced Hayloft Chorus. But the heart of the Barn Dance was in the intimate and familiar presentations of small groups like Mac & Bob, Jo & Alma, Karl & Harty, the Flannery Sisters, Lulu Belle & Scotty, The Girls of the Golden West, Linda Parker with the Cumberland Ridge Runners, The Three Maids (the Overstake Sisters), and Winnie Lou & Sally (named for WLS). Notice how many of these artists are women. What could be more homey and domestic than that

The Royal Telephone by Happy Valley Family (with Jo & Alma), 1935

Come Back to the Hills by the Flannery Sisters, 1936

I'm Riding on a Rainbow by the Overstake Sisters (aka The Three Maids), 1935?

Go to Part 2, pp. 37-71

NOTES for Part 1 (pp. 17-37)

Where would I be without my friends who collect ideas, old scraps of information, and 78rpm phonograph records? I've been able to hear National Barn Dance artists I'd never heard before because the following people generously made tape copies for me: Kerry Blech, Bob Bovee, Joe Bussard, Wayne Daniel, Paul Gifford, Frank Mare, Matt Neiburger, Jim Nelson, Paul Wells and the Old Town School of Folk Music's Resource Center. Jim Nelson also loaned me his complete run of Stand By!s and WLS Family Albums.

1. Dallas Morning News December 1, 1922, p. 1, sec. 2; Bill Malone, 'Country Music, U.S.A.', rev. ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1985), 33-34.

2. "A Brief History of WBAP Radio," www.wbap.com/article.asp?id=146501; "You Hear These Every Saturday Night," 'WLS Family Album, 1931'' (Chicago: Prairie Farmer Publishing), 43.

3. George C. Biggar, "The WLS National Barn Dance Story: The Early Years," 'JEMF Quarterly'' 6 (1970): 106; "Jazz Rules City Dance; Old Favorites Hold Country," 'Chicago Evening Post Radio Magazine'' (May 8, 1924): 16.

4. Boris Emmet & John E. Jeuck, 'Catalogues and Counters: A History of Sears, Roebuck and Company'' (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1950), 623.

5. James F. Evans, 'Prairie Farmer and WLS: The Burridge D. Butler Years'' (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1969), 216, 224.

6. 'Ibid., 62ff; List'ning In . . ., 'The Prairie Farmer'' (April 15, 1933): 8.

7. "WLS Foremost in Radio Surveys," in 'WLS Family Album'' (Chicago: Prairie Farmer Publishing, 1930), 35; Evans, Prairie Farmer and WLS, 202.

8. Biggar, "WLS National Barn Dance Story," 110; List'ning In . . ., 'The Prairie Farmer'' (August 5, 1933): 8.

9. 'Prairie Farmer'' (October 14, 1933).

10. Biggar, "WLS National Barn Dance Story," 109.

11. 'Ibid., 110; List'ning In . . ., 'The Prairie Farmer'' (Sep. 30, 1933): 8; Evans, 'Prairie Farmer and WLS'',1-2. Patsy Montana with Jane Frost, 'The Cowboy's Sweetheart'' (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2002),124.

12. “National Barn Dance Tonight,” 'Chicago Herald and Examiner (April 19, 1924).

13. Robert Shelton, 'The Country Music Story: A Picture History of Country and Western Music, (Secaucus, N.J.: Capitol Books, 1966), 42.

14. Two other local newspapers noted in their program listings, “This will be a regular Saturday night feature.” Radio Programs, 'Chicago Evening-Post and Literary Review (April 19, 194); Our 23-Hour Program, 'Chicago Evening American (April 19, 1924): pt. 2, p. 5; 'Kankakee Daily Republican (November 18, 1924).

15. Wayne Daniel, “National Barn Dance,” in 'The Encyclopedia of Country Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 372-73; see Chicago Tribune, Chicago Evening Post, and Radio Digest.

16. Wayne D. Daniel, "The National Barn Dance on Network Radio: The 1930s," 'Journal of Country Music 9 (1983), 47.

17. Ivan M. Tribe, “National Barn Dance, The,” in 'Century of Country, www.countryworks.com; Douglas Gomery, “WLS Barn Dance,” in 'The Encyclopedia of Chicago, ed. James R. Grossman, Ann Durkin Keating, and Janice L. Reiff (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 883.

18. Tony Russell, 'Country Music Records: A Discography, 1921-42 (New York: Oxford University Press), 2004.

19. 'Ibid., 3; “Anyone who was really keen could try counting the recorded masters on each of 31 randomly selected pages and multiplying the total by 30 (since the discography proper occupies 933 pp).” Tony Russell, personal communication, 2005.

20. D. K. Wilgus, “Country-Western Music and the Urban Hillbilly,” 'Journal of American Folklore 83 (April-June, 1970): 159; Kristine M. McCusker, “‘Bury Me Beneath the Willow’: Linda Parker and Definitions of Tradition on the National Barn Dance, 1932-1935,” 'Southern Folklore 56 (1999): 227ff.

21. These descriptions, as well as those in the previous paragraph, are taken from various 1930s editions of the WLS Family Album.

22. Quoted in Jeffrey J. Lange, 'Smile When You Call Me a Hillbilly: Country Music's Struggle for Respectability, 1939-1954 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2004), 27.

23. Bill C. Malone, 'Country Music, U.S.A.: A Fifty Year History (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968), viii; Malone, Country Music, U.S.A., rev. ed., 1.

24. D. K. Wilgus, “An Introduction to the Study of Hillbilly Music,” 'Journal of American Folklore 78 (1965): 196.

25. Lange, Smile When You Call Me a Hillbilly, 27; Charles K. Wolfe, “The Triumph of the Hills: Country Radio, 1920-50,” in 'Country: The Music and the Musicians, From the Beginnings to the ’90s, ed. by Paul Kingsbury for the Country Music Foundation, 2nd ed. (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994), 50.

26. Bernard L. Asbel, “The National Barn Dance,” 'Chicago 1 no. 8 (October 1954): 23; Biggar’s discussion, from a unpublished 1967 paper, is paraphrased in Evans, Prairie Farmer and WLS, 229.

27. This development was ubiquitous, for though the field of country music emerged in large part from old-time fiddling–a tradition of instrumental music with no lyric content of real importance–country music as heard on the radio and found on hit singles over at least the last fifty years has been almost exclusively vocal and lyrical.

28. “Kenosha Fiddlers Win Honors in WLS Contest,” 'Chicago Evening Post and Literary Review (September 27, 1924); “Barn Dance Callers in Contest on WLS,” 'Ibid. (April 15, 1926); “72 Callers Ready for WLS Barn Dance Contest Saturday,” 'Ibid. (March 17, 1927).

29. In a similar study of live country music on midwestern radio stations in the 1940s, radio artists and executives from that era used the terms “legitimate” and “hillbilly” to distinguish two varieties of musicians. I was told that union rules required a station to hire a “legitimate musician” for every country or “hillbilly” musician on their staff. Paul Tyler, “Country Music in the Cornbelt: WOWO - Fort Wayne in the 1920s and ’30s,” unpublished paper delivered to American Folklore Society, Nashville, 1982.

30. Ann & Norm Cohen, "Folk and Hillbilly Music: Some Further Thoughts on Their Relation," 'JEMF Quarterly 13 (1977): 52.

31. A similar symbolic reconfiguration was enacted elsewhere in rural America, as I described in a study of a mid-twentieth century transition of square dancing from kitchen hops to actual barn dances. Paul Tyler, “Square Dancing in the Rural Midwest: Dance Events and the Location of Community,” in 'Communities in Motion: Dance, Community, and Tradition in America’s Southeast and Beyond, ed. By Susan Eike Spalding and Jane Harris Woodside, Contributions to the Study of Music & Dance, no. 35 (Westwood, CT: Greenwood Press, 1995), 38ff.

32. See, for example, the picture of WLS’s Merry-Go-Round show, where seven of the thirty cast members pictured are holding a guitar, WLS Family Album , 1941: 10th Anniversary, p. 15; and the three guitars held by the seven musicians pictured with “Here Are Some Folks You Hear Weekly,” WLS Family Album , 1930 Edition: The Happy Radio Home, p. 43; Hoyt “Slim” Bryant, telelphone interview with author, August 13, 2005.

33. See William Howland Kenney, Recorded Music in American Life: The Phonograph and Popular Memory, 1890-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); and Diane Pecknold, “The Selling Sound: Country Music, Commercialism, and the Politics of Popular Culture, 1920- 1974” (Ph.D. diss., Indiana University, 2002), for insightful discussions on the practices of cultural production.

34. WLS Family Album, 1930, 12; 1931,11; 1935, 25; and 1939, 45.

35. Bryant, interview with author.