In 1944, two fiddle tunes were printed in California Folklore Quarterly, then a new academic journal still published as Western Folklore. One tune appeared in a note authored by Homer H. Kurtz; the other in a description of The Homer H. Kurtz Collection of Fiddler’s Tunes. (Click here to download both Homer Kurtz articles.)

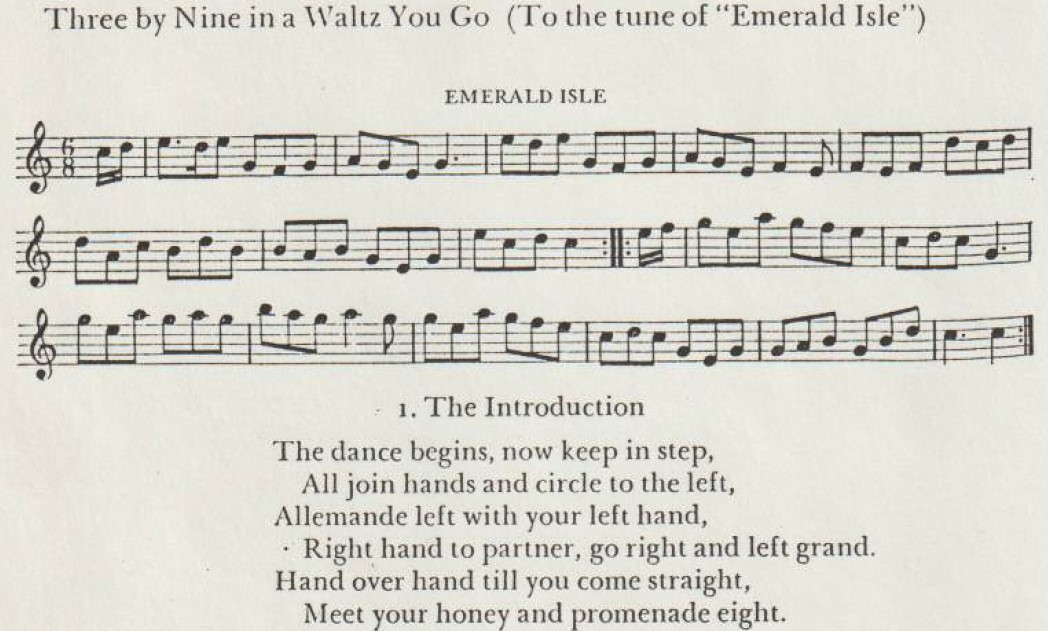

Kurtz himself wrote a short piece about a traditional square dance figure and gave a tune to go with it.

“Emerald Isle” – In western Ohio and eastern Indiana several fiddlers played this tune some forty years ago for the square dance, “Three by Nine in a Waltz You go.” It was played in regular square-dance time and seemed to fit in exactly with the call. I have never heard the tune or seen the dance in any other part of the country. Try it, you square dance lovers! (“Emerald Isle.” California Folklore Quarterly vol. 3 no. 3 (1944): 262-64.)

Here is the entire text of the note describing the Kurtz Collection by an unidentified author:

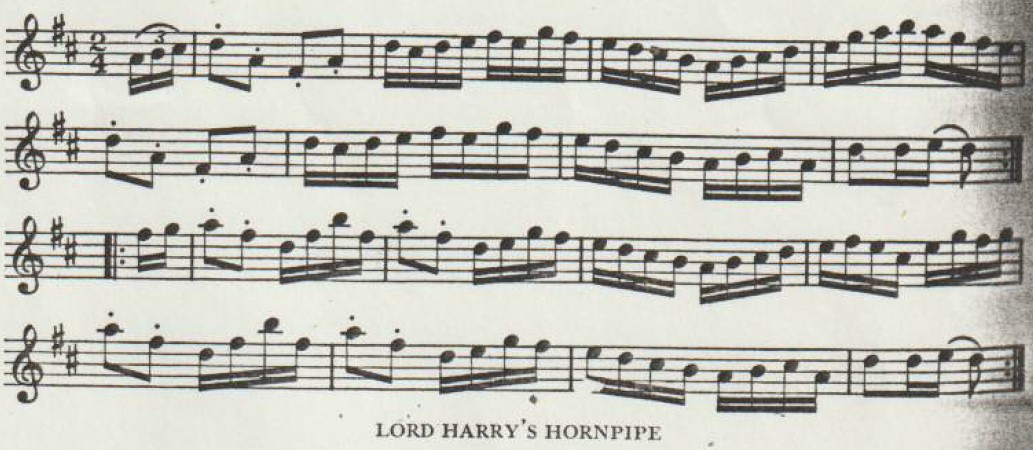

This important collection consists of 563 pieces of music. It includes 68 hornpipes, 112 jigs, 164 reels, 75 waltzes, 26 schottisches, 11 polkas, 23 marches, 12 clogs, 7 flings, 43 songs, 2 cakewalks, 19 twosteps, and 1 minuet. It represents the labor of more than forty years, during which time the collector has noted down the music. Mr. Kurtz was born in eastern Indiana on the banks of the Wabash River in 1889. Tunes of this sort were the common dance music of the region. More than 90 items in this collection have never been printed, so far as the collector can learn. Mr. Kurtz gives us the following sample tune. “Lord Harry’s Hornpipe” is a tune known to all oldtime fiddlers in eastern Indiana and western Ohio a half-century ago. It was especially popular as a tune for square dances. (California Folklore Quarterly v. 3 no. 2 (1944), p. 160.)

Listen to Lord Harry’s Hornpipe played by Vox Elders, September 2024

(Paul Tyler-fiddle, Fred Campeau-banjo, Michelle Thomas-ukulele, Gail Tyler-bass)

It is likely that one of the Quarterly’s editors, S.B. Hustvedt or Archer Taylor, wrote the descriptive paragraph above. Hustvedt, who graduated from Luther College in Decorah, Iowa in 1902–115 years before my daughter did–was a renowned ballad scholar. Archer Taylor was an eminent folklorist who has his own Wikipedia entry. Homer H. Kurtz was not heard from again in academic folklore circles.

I became aware of the Homer H. Kurtz Collection of Fiddler’s Tunes back in 1976 or soon after, probably from Charles Haywood’s two-volume Bibliography of North American Folklore and Folksong, published in 1961. I made a few unsuccessful attempts to locate the collection in a university library or archives. Then twenty years later, I went to much greater lengths to find out what happened to this corpus of over 500 fiddle tunes, including many from my home region of northeastern Indiana, right along the state line with Ohio. Once again I came up empty. However, I did find a few more traces left behind by Homer Kurtz. His story is still intriguing, and perhaps the pursuit should be resumed once more.

Here is what I have learned.

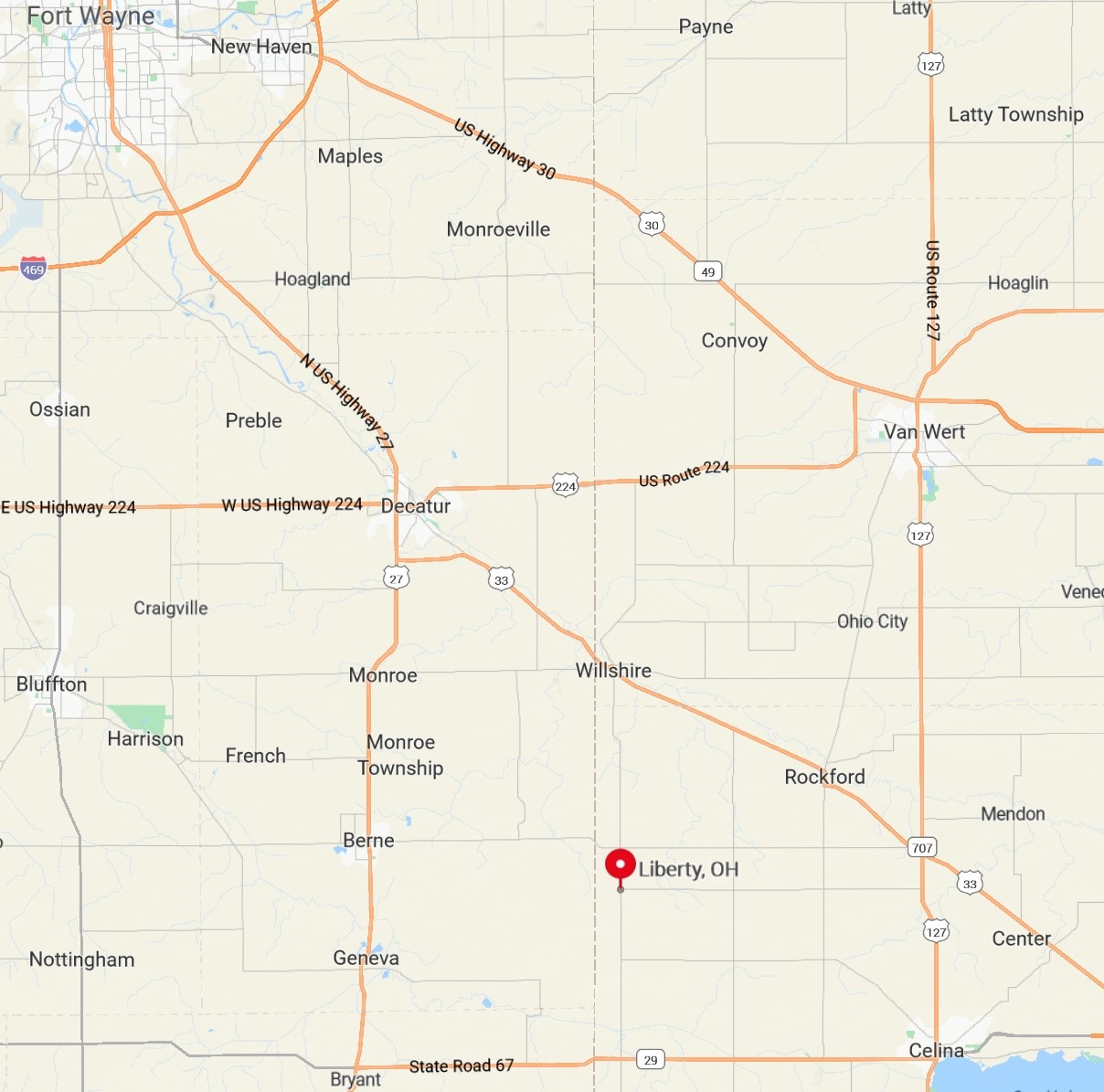

Homer Horton Kurtz was born on June 6, 1889 in Jay County, Indiana, in or near the town of Bryant. His father Charles Kurtz (spelled Kurts by a 1900 census taker) was born in Ohio. His mother, Julia Butcher, was a native of Indiana. By the time of the 1910 census, the Kurtz family (taken down for this census as ‘Curtis’) was living in Liberty Township just across the state line in Mercer County, Ohio. Now in his early 20s, according to the census, Homer was no longer in school, though he could read and write, and was still living in his father’s household. He was listed as a wage earner.

I have not yet found an entry in the 1920 census for Homer. His father Charles E. Kurtz, however, is found in both the 1920 and 1930 censuses as resident in Wabash Township in Jay County, Indiana, immediately adjacent to Liberty Township in Ohio. The 1930 census shows that Homer had relocated to Kaw City, Oklahoma, where an oil boom on the Osage Reservation had made jobs plentiful. That census lists Homer’s occupation as oil industry laborer.

Based on his later “collection of fiddler’s tunes,” it appears that Homer Kurtz must have taken up the fiddle at a relatively early age and spent much of his teenage and young adult years playing for “country dances and entertainments”–and hanging out with older fiddlers– in his native district along “the banks of the Wabash River” in Indiana and Ohio. The headwaters of the Wabash are, by the way, near the village of Fort Recovery in Mercer County, Ohio.

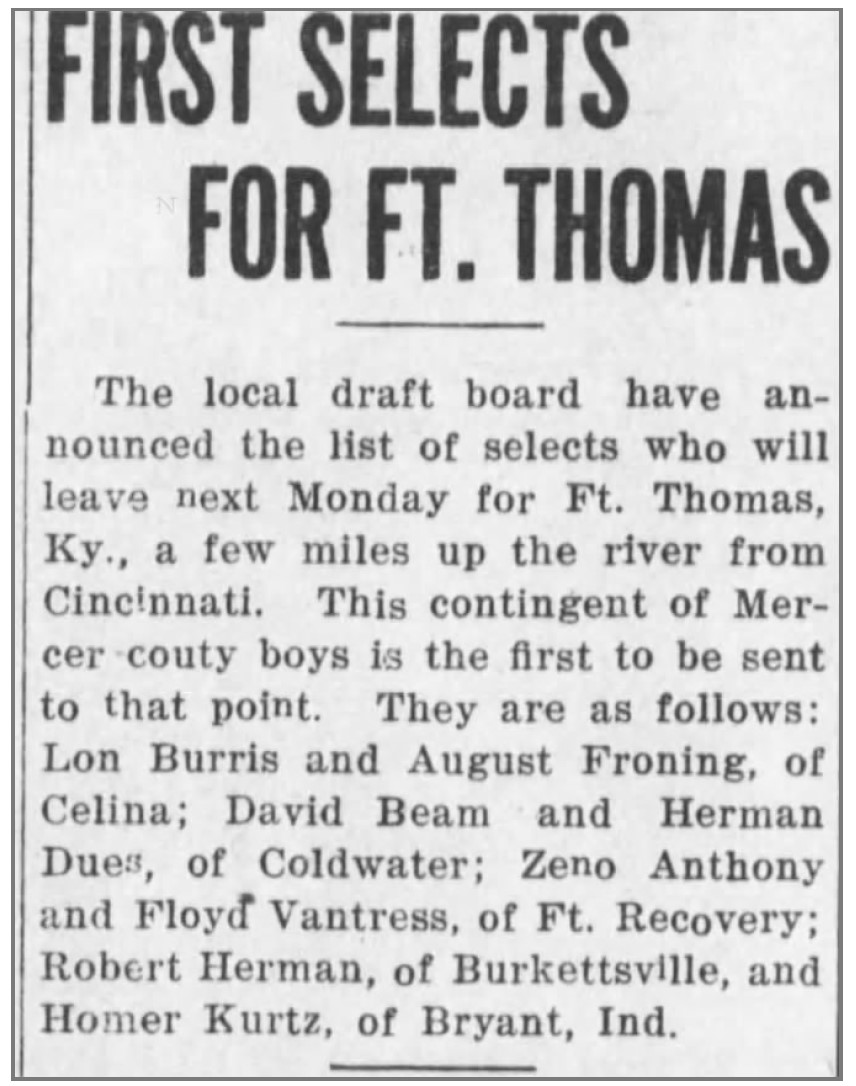

In 1918, Homer Kurtz registered for the World War I draft, and was one of the first young men from the district to ship out from Celina, Ohio to Fort Thomas, Kentucky. (An interesting side note shows some of the fluidity of living in a rural district along a state line: a news article from the Celina Democrat identifies Homer Kurtz of Bryant, Indiana as a “Mercer County boy.”)

Life events picked up quickly after his discharge from the army. In 1920 he obtained a marriage license in Arkansas City, Kansas with Elsie Adams, a native of that state. Within three years, they were living in Kaw City, Oklahoma, where Elsie gave birth to two sons, Kenton, born circa 1923, and Harlan Leon born in 1924 or ‘25.

The Kurtz family resided in Oklahoma over a span of least twenty years. Both Homer and Elsie were in Oklahoma when they signed up for Social Security at some point after 1936. When he registered for the World War II draft, he gave his place of residence as Kaw City, Oklahoma.

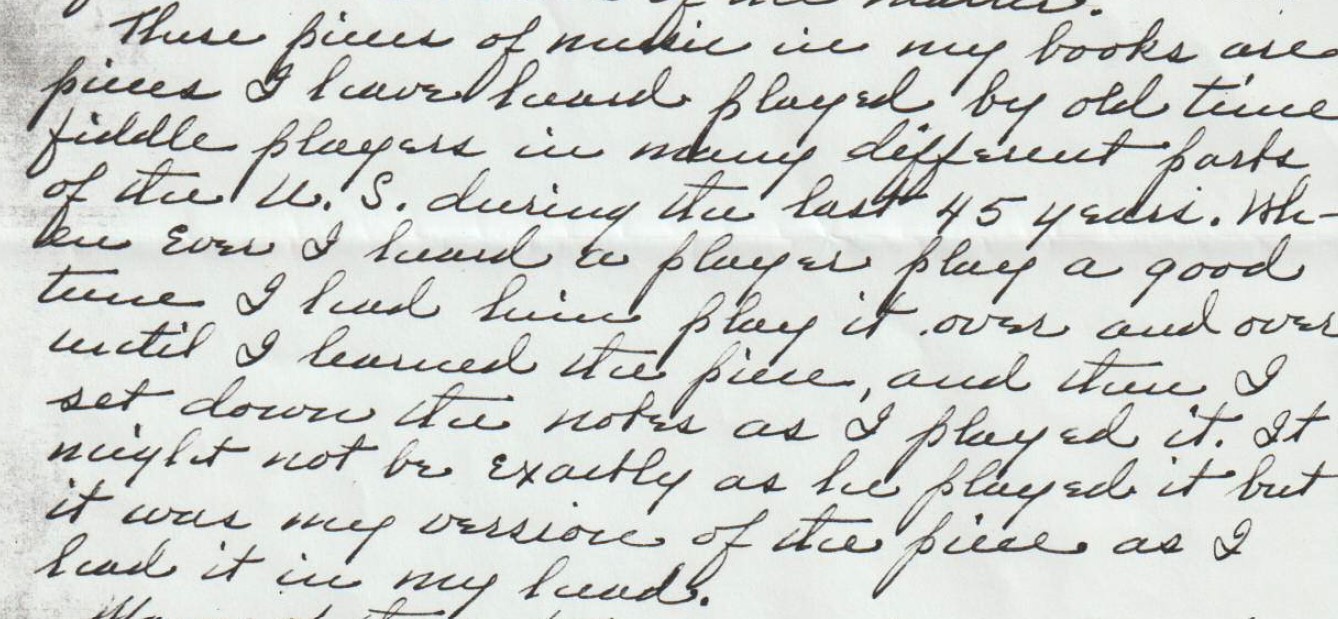

The one surviving letter we have in Homer’s hand mentions learning fiddle tunes in many places:

These pieces of music in my book are pieces I have heard played by old time fiddle players in many different parts of the U.S. during the last 45 years. When ever I heard a player play a good tune I had him play it over and over until I learned the piece, and then I set down the notes as I played it. It might not be exactly as he played it but it was my version of the pieces as I had it in my head. (Letter to August Fruge, University of California Press, dated July 24, 1946.)

Though we don’t know the exact circumstances, it appears that the Kurtz family moved to Richmond, California to work in the shipyards as part of the early 1940s war effort. The four Kaiser Shipyards there had great need for Rosie the Riveters and men too old for the draft. (An astounding number of ships–786–were built in Richmond during the war.) When he published his note on “Emerald Isle” in the folklore journal in 1944, Homer identified himself as from “Richmond, California.”

According to Richmond City Directories, the Kurtz family lived at 451 11th Street through at least 1957. Some directories in the 1950s list son Harlan as a member of the household. Homer’s occupation was listed as “carpenter,” while Harlan’s is given variously as “driver” and “warehouseman.” From Homer’s letter quoted above, we know also that Harlan “plays second part on the guitar.”

By 1962 Homer Kurtz was living in Los Angeles, where he registered to vote as a Democrat. He died in June 1981. His last residence was Inglewood in Los Angeles County. His wife Elsie (born in 1897) died in the same place in 1988. They both lived into their 90s.

The truth is, Homer Kurtz was heard from again by just a few members of the academic circle of folklorists, including August Fruge, an editor at the University of California Press, and Bertrand Bronson of the English Department at the University of California in Berkeley. In a response written on Sept. 20, 1946 to Homer’s letter from July (quoted above), Fruge referred the matter of Homer’s fiddle “books”–i.e., handwritten manuscript notebooks–to Prof. Bertrand Bronson, an esteemed ballad scholar who specialized in the traditional tunes to which the old popular English and Scottish ballads were sung on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. He promised the professor would be in touch.

Homer’s letter was located in Bronson’s papers circa 1997 by friend and fellow folklorist Lani Herrmann. She shared it with me nearly 30 years ago. It presents a very intriguing exchange between members of the elite and one of the folk, the folk music scholar and the working class musician. Please note that the working man in question had skills and knowledge aplenty, but little formal education; certainly none beyond high school. He states his case well:

There are almost 100 of these pieces in the books, I have never saw in print before. The rest of the pieces have been published before in various books but my version is not as they have them. There isn’t a single piece in my books that is exactly like those in other books.

In all my years of playing the fiddle for country dances and entertainment I am the only one I ever heard of who could learn tunes by ear and then know enough about music to set down the notes on paper.

It would be better for me to meet you personally and talk over many things with you.

This exchange suggests that there was some interest on the part of the scholars in Homer Kurtz’s “books.” But he was employed on weekdays until 4:30 P.M. He had neither an automobile nor a telephone. If he had to go to Berkeley to meet the scholars, he would have to take a bus and would not feel comfortable carrying his instrument on public transportation–perhaps because he did not have a case for his fiddle and bow, and a flour sack would be too insecure . . . or too embarassing? If they wanted to call him to set a time to visit him in Richmond, they would have to call his neighbor, who would fetch him to the phone. Homer was willing to meet in Berkeley or Richmond on any Saturday after 10 A.M.

The trail of the Homer H. Kurtz Collection of Fiddler’s Tunes is faint, but suggestive. Somehow he brought his “books” to the attention of Hustvedt and/or Taylor, editors of the California Folklore Quarterly. One of them, or another member of the editorial board, apparently analyzed the collection and enumerated its contents according to tune/social dance genre. The description published in issue number two of the 1944 Quarterly is quite tantalizing for fiddle tune enthusiasts. The next number of the journal included Homer Kurtz’s transcription of another tune–one of the jigs–and a square dance figure.

Two years later, Kurtz was discussing the possibility of publishing the collection with Fruge, an editor at the University California Press editor. Kurtz’s letter is a response to a missive from Fruge received only two days before Homer took pen in hand. I have seen only Fruge’s subsequent response, referring the matter to Prof. Bronson. What was the nature of his earlier letter to Kurtz?

For that matter, where were Homer’s notebooks between 1944, when they were noted in the California Folklore Quarterly, and 1946 when letters were exchanged? Did Homer Kurtz give his notebooks over to the custody of academic folklorists? I find it hard to believe that he had a second copy of his original manuscripts, unless he committed himself to the labor of making multiple copies of handwritten transcripts of 563 fiddle tunes.

Apparently, Professor Bronson did nothing about Homer Kurtz’s tune books. Not in 1946 or thereafter. When the Kurtz family moved to Los Angeles for Homer’s last two decades on this earth, did his original manuscripts go with him? I have been unable to locate them in any libraries or archives in California or elsewhere.

The larger cultural context of this exchange raises further questions, some rather unsettling. What is the public value of the lore, knowledge, and arts of the common folk? And who controls the narrative? Their meanings?

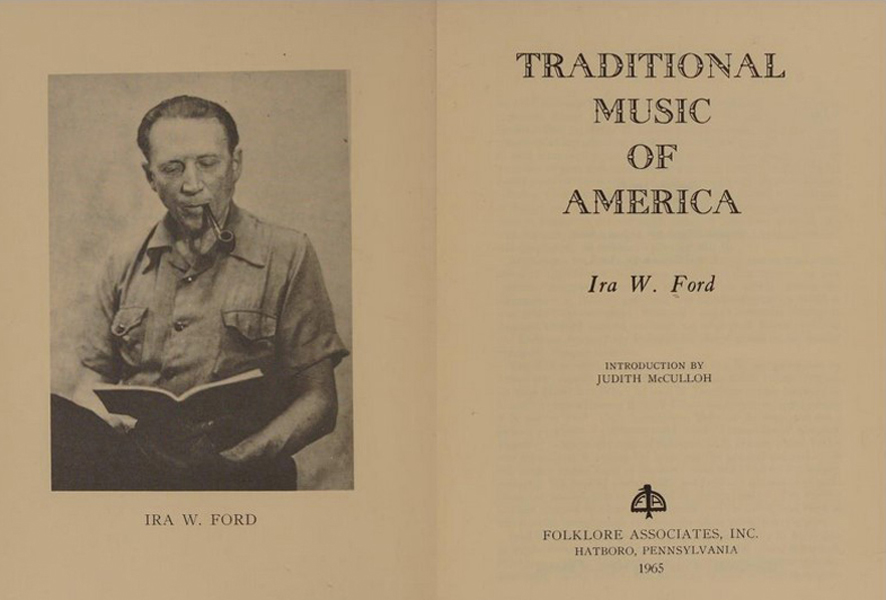

In 1940, E.F. Dutton published Traditional Music of America, a collection centered around a corpus of fiddle tunes compiled by Ira W. Ford in Missouri and California through methods very similar to Homer Kurtz’s mode of operation. In a review published in the very same issue of the California Folklore Quarterly in which the Kurtz Collection was noted, Ford’s book was panned for lacking interest “for the critical student.” The reviewer, J. Olcutt Sanders, found that the Ford Collection was not up to the standards of the academic folklorists of the day. The compiler provided no documentation of provenance or identification of sources for the items in his collection.

Whether the Kurtz Collection would have provided further information about where the tunes were collected, or from whom, cannot be ascertained until the collection is located. Even then, I am led to wonder if that is one of the “many things to talk over” had Prof. Bronson and Homer Kurtz ever met. My hunch is that Mr. Kurtz did not include consistent data about his sources in his notebooks, but that, upon request, he would have been able to provide much more information from a credibly capacious memory.

Possibly a more pressing concern for the academic folklorists was Mr. Kurtz’s description of his collecting methods. He learned each tune aurally from multiple requested performances by a fellow folk musician. I can easily imagine the scientific collectors from the academic community being put off by the imposing subjective presence of the collector in the Kurtz notebooks.

Two responses, however, come immediately to mind: 1) Mr. Kurtz was not an outside observer, but a participant in the expressive communities that sustained traditional fiddling, and 2) even more detached “objective” transcriptions involve a selective translation of some aspects of a musical performance into a fixed visual, symbolic representation. The translation processes of Mr. Kurtz and a scientific folklorist may differ in degree, but not in kind. Mr. Kurtz, however, was privy to certain aspects of insider information that would not be readily apparent to the outsider. In his letter to Fruge, Kurtz intimates that he fully understands the insider/outsider (emic/etic) dynamic. He requested that at any future meeting “I would like for you to have somebody present who thoroughly understands and plays this type of music.”

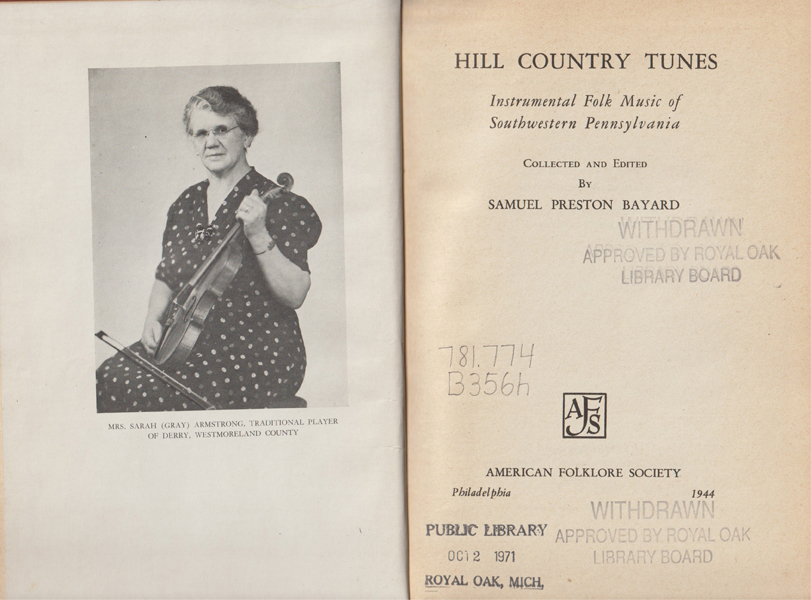

Coincidentally, 1944 was also the year in which Prof. Samuel Preston Bayard of Pennsylvania State University published Hill Country Tunes: Instrumental Folk Music of Southwestern Pennsylvania (Memoirs of the American Folklore Society, Vol. 39). This small volume of 99 fiddle tunes noted down from the playing of Sarah Armstrong and a half dozen other traditional fiddlers–a few tunes were copied from a fifer’s manuscript collection–was a rich precursor to Bayard’s Dance to the Fiddle, March to the Fife, published nearly four decades later. This latter work, which covered the same geographical territory, contained well over a thousand tunes and, like the earlier Hill Country Tunes, copious analytic and comparative head notes. The musical notations in both volumes were transcriptions or translations of aural folklore into written notation.

Many of the transcriptions in the later work were taken down from listening to performances recorded on reel-to-reel tapes. Hill Country Tunes, on the other hand, like the Kurtz Collection, relied solely on aural memory. We do not, however, have a clear statement from Prof. Bayard of his mode of operation that can compare with Homer Kurtz’s honest disclosure of how he translated sound data into symbolic notation. Once again, I think we are dealing with a difference of degree rather than of kind. I am not convinced that Prof. Bayard’s method is inherently more scientific than the way followed by Homer Kurtz.

Don’t get me wrong. I am grateful for the opportunity to read through and study both of Bayard’s tomes. In a similar, though somewhat lesser manner, I benefit from the time I have invested in Ira Ford’s Traditional Music of America. But I deeply regret that I have not been able to get my hands on the Homer H. Kurtz Collection of Fiddler’s Tunes. I can only imagine what musical treasures lay within.

My regrets and longings are magnified by the fact that the Kurtz Collection had its origin just two counties south of my hometown, in a district that was wild about square dancing back in the 1950s and ‘60s when I was growing up. Strangely, musical tastes in my hometown in Allen County, Indiana had turned more modern, and the bands I danced to as a youngster never featured fiddlers. When I began to inquire after the older fiddlers who had once played for dances around there, I was told of the annual Fiddlers’ Reunion held in Ryel’s Woods outside of Payne, Ohio. Just across the state line, Payne is about 50 miles from Homer Kurtz’s hometown of Bryant, Indiana. If, as according to stories I was told, the Fiddlers Reunion was initially held before or just after World War I, it is highly likely that Homer Kurtz would have participated. (It was revived again in the 1920s after Kurtz had moved on to Oklahoma.)

When I began my search for Indiana fiddlers, one of the first legendary players I heard about was Kenny Roth from Adams County, with a Rural Route #5 postal address out of Decatur. Otto Kenneth Roth was born just four years before Homer Kurtz, and because they lived within 25 to thirty miles of each other, I am willing to bet that Homer Kurtz included a Kenny Roth tune or two in his collection. Here is a Kenny Roth tune as recorded by Harold Zimmerman of Fort Thomas, Kentucky in 1997 for the Rounder Records CD, Along the Ohio’s Shores (now available as Field Recorders Collective FRC731).

Harold Zimmerman was born and raised in Convoy, Ohio just north of Mercer County. He learned to play, in part, from his grandfather George Knittles, who lived in Pleasant Mills, Indiana, just 23 miles from Homer Kurtz’s hometown of Bryant. When I interviewed him in 1980, Mr. Zimmerman told stories of music parties at his grandfathers home at which Kenny Roth was a frequent participant. Was Homer Kurtz part of this circle of country fiddlers?

The loss of the Homer H. Kurtz Collection of Fiddler’s Tunes, has an adverse impact that surpasses even my own personal disappointment. It would have been valuable for folklorists and fiddle enthusiasts alike to have a corpus of tunes from pre-World War II traditional performance contexts in other regions to supplement the rich material in Bayard’s contemporaneous Hill Country Tunes.

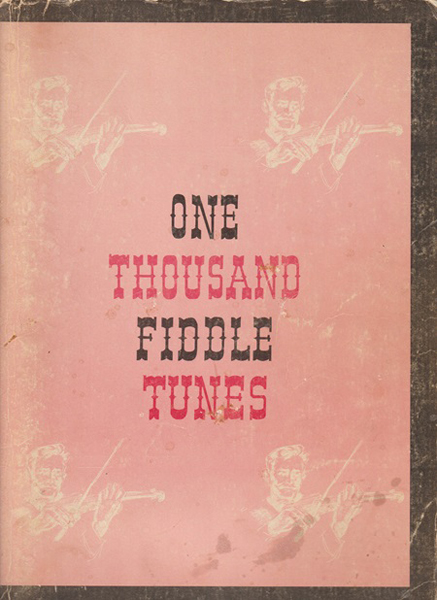

It is worthy of notice that the 1940s also saw the publication of the so-called “fiddler’s bible”: M.M. Cole’s One Thousand Fiddle Tunes. A re-shaping of Ryan’s Mammoth Collection from Elias Howe in Boston in 1883, the edition published in Chicago in 1940 was highly esteemed by all manner of fiddlers in North America, even by many who did not read music. But as valuable as it was as a source and resource, Cole’s does not provide an accurate measure of traditional repertories and performance practices. The promise of the Kurtz Collection was to bring us closer to the dances and entertainments of rural districts in at least Indiana, Ohio, and Oklahoma. And then there are the 90 to 100 pieces that Mr. Kurtz declared had never before seen print.

It is worthy of notice that the 1940s also saw the publication of the so-called “fiddler’s bible”: M.M. Cole’s One Thousand Fiddle Tunes. A re-shaping of Ryan’s Mammoth Collection from Elias Howe in Boston in 1883, the edition published in Chicago in 1940 was highly esteemed by all manner of fiddlers in North America, even by many who did not read music. But as valuable as it was as a source and resource, Cole’s does not provide an accurate measure of traditional repertories and performance practices. The promise of the Kurtz Collection was to bring us closer to the dances and entertainments of rural districts in at least Indiana, Ohio, and Oklahoma. And then there are the 90 to 100 pieces that Mr. Kurtz declared had never before seen print.

If by some chance any reader has knowledge of the whereabouts of the Kurtz Collection or any descendants or relatives of Homer H. Kurtz, please let me know. Also, if any independent researchers would like to look for the Kurtz Collection in the Archer Taylor papers at the University of Georgia or in the Bertrand Bronson papers at the University of California, please get in touch.

You may contact me at hoosierfiddle@gmail.com.

Paul L. Tyler, PhD (DrDosido)