Listen on Midwest Fiddle Bands 1 (DDCD-101 ) – click here for the discography.

Also on Midwest Fiddle Bands 2 (DDCD-102 ) – click here for the discography.

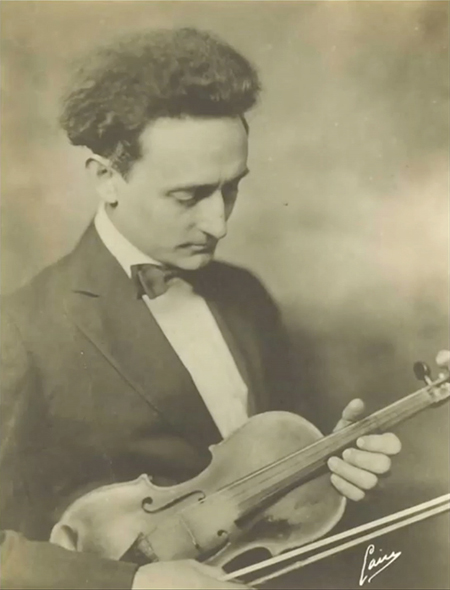

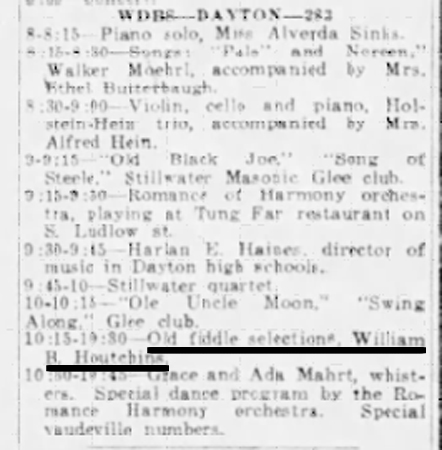

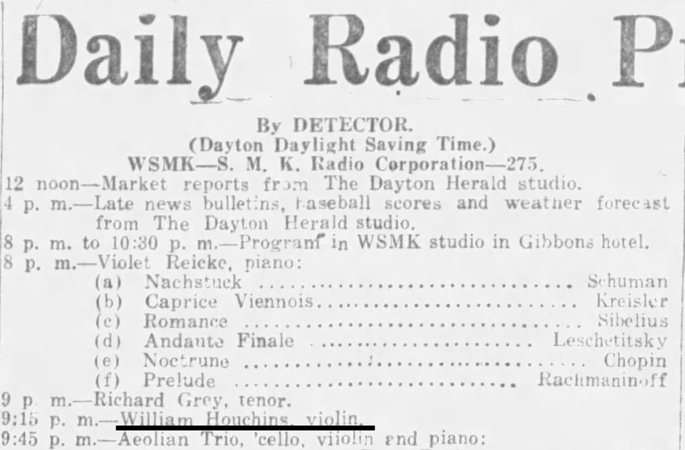

The career of William B.Houchens seems to have crested in the first half of the 1920s, as he approached his fortieth birthday. For three years running, from 1922 to 1924, he made the 50-mile journey from his home in Dayton, Ohio to the Gennett studios at the Starr Piano Company in Richmond, Indiana. At his four sessions, he recorded 32 traditional fiddle tunes on 17 masters. Fourteen sides (7 discs) were released for sale. In March of 1924, he appeared on WLW, a new radio station in Cincinnati that would grow into a regional power house (“the nation’s station”). A few months later, he appeared on WDBS in Dayton performing “Old fiddle selections.” After 1926, when his fiddling was praised in a newspaper review, Houchens career faded into obscurity.

Houchens is best known, if at all, for being one of the earliest fiddlers to perform on a phonograph record. On September 18, 1922 he recorded three sides for Gennett. This was less than three months after Henry C. Gilliland and Alexander Campbell “Eck” Robertson , from Oklahoma and Texas respectively, ventured into the Victor offices in New York and talked their way into a recording session. The Gilliland and Robertson recordings are now deeply ingrained in the legends that narrate country music’s origins. William B. Houchens has been mostly forgotten.

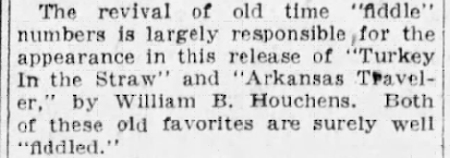

Nevertheless, the stories of those early recording sessions display some intriguing parallels. Of the four sides Gilliland and Robertson waxed on June 30, 1922, only Arkansas Traveler and Turkey in the Straw were issued, and not until the following year. The next appearance in the studio by either was the 1929 session by A.C. Robertson & Family. Houchens also recorded these two popular titles at his first session. While Gilliland and Robertson’s performance were only issued once by the Victor Talking Machine Company during the 1920s, Houchens pairing was issued five times on four separate labels: Gennett, Champion, Challenge, and Apex. As noted in the Star article above, Gennett took advantage of the old-time fiddle revival of the mid-1920s to promote sales of the earliest fiddle records in their catalog.

But first, a worthwhile digression into the conundrum of the first fiddler to record. A few years ago, historian Pat Huber made the case for Don Richardson from North Carolina being the first country fiddler to record. Like Houchens, he was a trained classical violinist who also had first hand knowledge of fiddling. In 1916, he recorded a dozen traditional tunes for Columbia. But, some will say, ‘He was a violinist, not a fiddler.’ On the other hand, I wonder if being a Southerner gives violinist Richardson more country fiddler credibility than is usually accorded to someone like bandleader and jazz violinist Joseph Samuels, who recorded a number of fiddle tune medleys between 1919 and 1922.

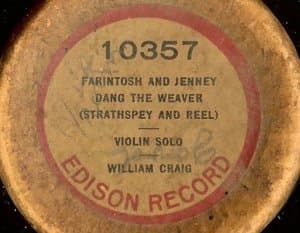

For my part, I submit that the earliest and oldest country fiddler to record was William Craig (1836-1911) of Kingston, Ontario. He immigrated from Scotland in 1851. In the 1901 Canadian census he gave his heritage as Scottish, his nationality as Canadian, his occupation as farmer, and his language as Scotch English. Around 1908 he recorded half a dozen cylinders for Edison. Most were strathspey and reel medleys. But, some will say, “He’s ethnic.” Still, one reel had a most American name, The Shores of Lake Erie, and his playing displays evidence of a half-century of living in North America, far from his native community.

Back to Wm. B. Houchens. While his performing career left only a few tantalizing traces in the media, in census records and city directories, he identified himself as a musician or music teacher from at least 1917, when he lived in Cincinnati, through 1946 in Dayton. According to a family memorial on FindaGrave.com, we know that he played multiple instruments, and that he taught violin and piano at the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music. After a brief residence in Hamilton, Ohio in 1920, he moved to Dayton, where he lived until his death in 1949. He opened his own music studio there in 1921, immediately prompting a lawsuit from a rival teacher on charges of student poaching.

In a brief historical sketch in Kentucky Country (1982), Charles K. Wolfe suggested that Houchens was more of a violinist that a fiddler. Wolfe reported that Houchens, a native of Alton, Kentucky, learned some of his music from his Missouri born mother, some from older fiddlers in his native Kentucky, and some from jig and hornpipe books. The musical and genealogical records, though sparse, tell a more nuanced story.

William Bright Houchens was, in fact, born in 1884 in Sharpsburg, Illinois, in Christian County between Springfield and Decatur. His father, James Henry Houchen was born in Shelby County, Kentucky in 1847. His mother, Mary Elizabeth Kennedy Houchen, or Molly, was born in 1854, in Missouri. The movements of his parents are hard to trace. James Henry, who worked as a school teacher, may have been teaching in Parke County, Indiana, according to the 1870 census, and Mary Elizabeth Kennedy may have, at the time, been a 14-year-old living in Hancock County, Illinois. It is more likely, according to the 1880 census, that Mary (or Molly) was either living on a farm in Benton County, Missouri or teaching school in St. Louis. (Molly, according to the family memorial above, did teach young Billy to read music.) No record of either parent has been found in the 1890 census. Mary died in 1895, when Billy was ten. The 1900 census locates the widowed James Henry and his 15-year-old son living on a farm in Anderson County, Kentucky in a household headed by Martha J. Brown, James’s older sister.

Young William enlisted in the army at Louisville in 1901. The army registry listed his age as 21–he was, in fact, 17–his occupation as musician, and his birthplace as Eddingburg, Illinois. Houchen was discharged at Fort Meade in 1904. I can find no record for William or his father in the 1910 census. By 1920, William had married Eula Lee Baird (1890-1947), a native of Tennessee, and they moved to Hamilton, Ohio, then Dayton, where they both lived till the end of their days. Once settled in Dayton, the couple took in William’s elderly father. James Henry died in Dayton in 1927 at the age of 80. Eula died in 1947 and William in 1949. However, shortly after Eula’s death William married Ada Jean Light (1896-1986) from Huntington, West Virginia. William, James, and Eula were each buried in the Lawrenceburg Cemetery in Anderson County, Kentucky near the grave of Molly Kennedy Houchens, William’s musical mother.

In 1922, Houchens went to Richmond to visit the Gennett recording studios for the first time.

Listen on Midwest Fiddle Bands 1 (DDCD-101 ) – click here for the discography.

Of the six tunes he recorded on that September day, two are untitled. In his recordings of both Arkansas Traveler and Turkey in the Straw, Houchens inserts an unannounced tune. I have not been able to identify the tune tacked on to latter title. In the former case, the extra tune was identified by Gus Meade as Shipping Port, which was recorded for Gennett again in 1933 by Andy Palmer, a native of Anderson County, Kentucky. Other versions of this rare tune were collected in the 1970s from three other traditional fiddlers from the same area. Also recorded at the 1922 session were two hornpipes: Liverpool and Durang’s. Both were frequently published in “jig and hornpipe” tunebooks. Houchens’s performance of these two standard pieces show off personal touches in his rhythmic bowing and in his shaping of the melodies. He did not strictly follow any published setting that I have been able to find.

In the first of two sessions in 1923, Houchens recorded five masters, each of which was a medley of at least two tunes. Of these dozen tunes, all but two are found by name in published tunebooks from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Houchens’s performances of some of the lesser known tunes, such as Kitty Clyde and Collins Reel, follow printed settings fairly closely, but not exactly. His playing of more common tunes, like Money Music and Irish Washerwoman, display his own personal take, with occasional double stops and drones, and with melodic variations and distinctive bowed rhythms. It should be noted that the latter is the only tune in jig time (6/8) that he recorded.

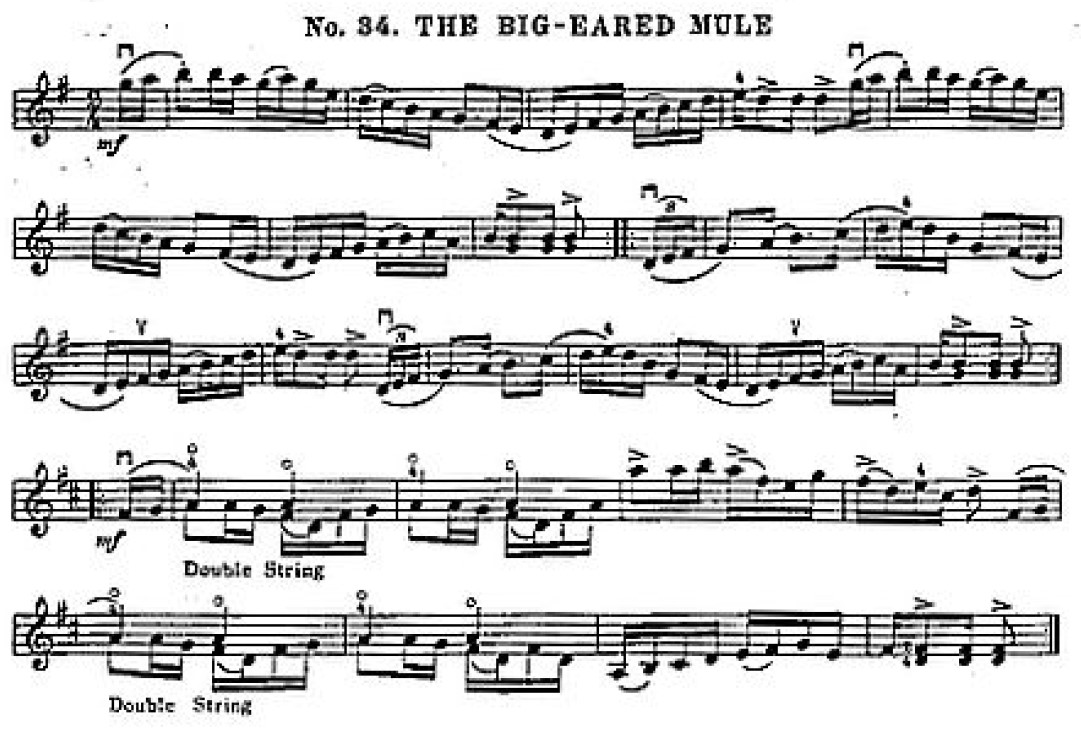

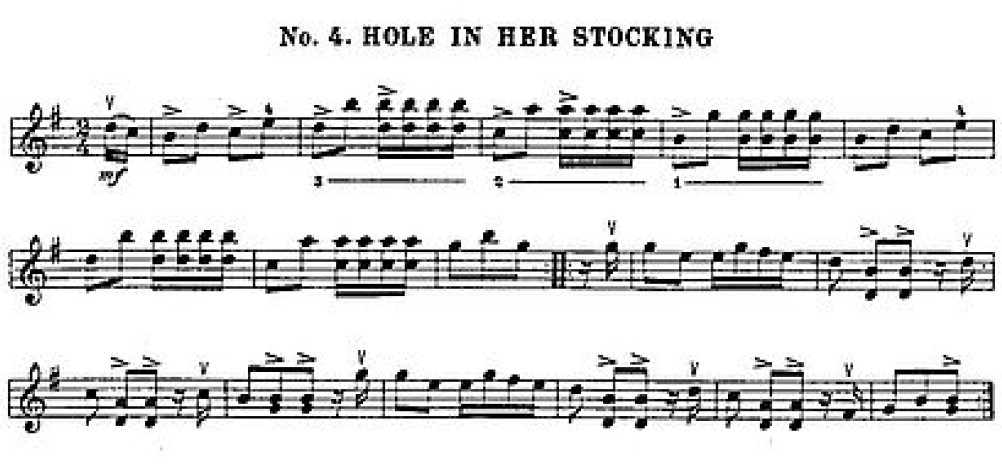

A most interesting case from this session is the medley of Dance Wid’ a Gal, Hole in ‘Er Stocking/ Leather Breeches/ Big-Eared Mule. Charles Wolfe named this the first commercial recording of Flop-Eared Mule. But only one of three strains in Houchens’s Mule resembles the ‘Flop-‘ or ‘Lop-Eared Mule’ still played often today. All three tunes in this medley are found in similar settings in E.F. Adam’s Old Time Fiddlers Favorite Barn Dance Tunes for the Violin (though Adam’s title for the first tune is just ‘Hole in Her Stocking’). The formal structure and keys of each of these tunes matches its printed counterpart, but the melodies are quite varied. There seems to be some connection, but Adam’s folio was published in St. Louis in 1928, five years after Houchens recorded this medley in Richmond. I take this as a sign of an active aural tradition in the region around the home state of Houchens’s mother Molly.

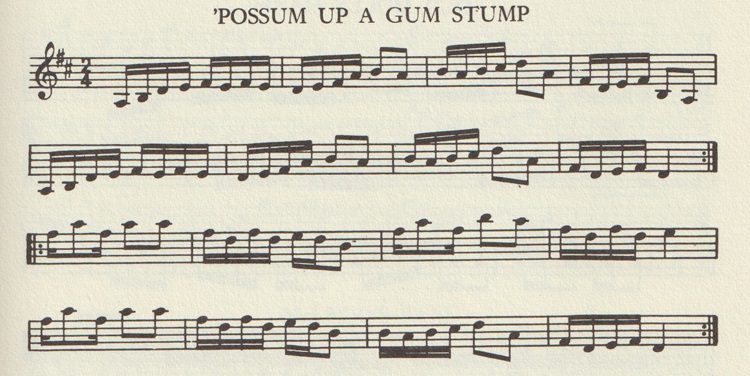

The two tunes from February 1923 with uncommon titles, Bob Walker and Hel’n Georgia, have particularly interesting histories. Wolfe stated they both were likely learned from old-time fiddlers in Kentucky. But the former belongs to the wide-spread Dubuque family of tunes. In the 19th century it was published in various Elias Howe publications as ‘Village Hornpipe’ or ‘The Gems of Ireland.’ E.F. Adam published it in 1928 as ‘Fiddling Phil.’ Gus Meade claims that ‘Sweet Ellen,’ collected in Pennsylvania by Samuel Bayard and published in 1944 in Hill Country Tunes, belongs to the same family. For me, Houchens’s Bob Walker calls to mind ‘Possum Up a Gum Stump’ in Ira W. Ford’s Traditional Music of America (1940). Ford, by the way, was from Missouri.

I know of another tune called ‘Bob Walker,’ played by John W. Summers of Wabash County, Indiana. It is an entirely different tune. Ironically, Summers may have learned it from Tom Riley, who moved several times between Marion, Indiana and his home state of Kentucky.

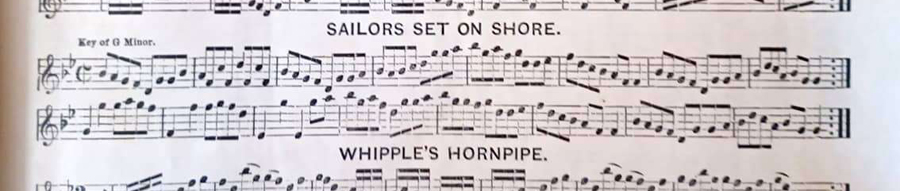

The latter supposed Kentucky tune, Hel’n Georgia, sounds more Celtic than Appalachian (to use currently popular genre labels). Gus Meade identified it as a 20th century variant of a 19th century tune known as ‘Sailors Set on Shore.’ The earliest published setting appeared in 1850 in Howe’s Original School for the Violin. But I discovered an even earlier setting from 1842, titled ‘Doctor Hanson’ in the handwritten tunebook of Ruben Fisher, who lived in Richland County, Ohio, 130 miles northeast of Dayton. A 20th Century setting was published as ‘Sailors on Shore’ in Ford’s Traditional Music of America. Though precise documentation is missing from Ford’s compelling, but frustrating collection, contextual evidence suggests that this reel in G minor may have had more currency in the Missouri and Central Plains fiddle traditions than in Central Kentucky.

Listen on Midwest Fiddle Bands 2 (DDCD-102 ) – click here for the discography.

An additional session in May 1923 led to the recording of three intriguing titles: Morris Dance, Torch Dance, and Old Kentucky Home. Sadly, these remain unissued and unfound. Houchens went back to the Gennett studios one more time in September 1924 and recorded six more masters, comprising 11 tunes. The first tune in the session was Wagner (aka Wagoner), which has all the hallmarks of aural tradition. The other ten tunes–paired in five medleys–are all played fairly close to printed settings. All ten of these settings are found in Charles H. McGee’s Old Time Jigs and Reels for the Violin, published in 1906 in Boston by Oliver Ditson. I would guess that this tunebook was possessed by Houchens.

Charles Wolfe was right that Wm. B. Houchens got part of his repertoire from local Kentucky fiddlers and part of it from published tune books. What we can’t ascertain are the connections between Houchens’s repertoire and the region further west, where his mother was born. Perhaps he learned some of his repertoire from his mother, who died when he was 10 years old. Or perhaps he tapped into other local scenes in the Midwestern cities where he spent time: from Louisville to Cincinnati, and from Hamilton, Ohio to Dayton.

At the three Gennett recording sessions that produced issued recordings, Saloma Dunlap accompanied Houchens on piano. Born Saloma Katherine Dunlap in 1903, she was a Dayton native, who graduated from St. Mary’s High School in 1921. The local papers from that time devoted more space to her achievements in art, theatre and music, than to coverage of Houchens’ doings. Indeed, according to the Dayton Daily News, she was “well-known in musical circles.” She is listed in city directories from 1922 to 1925 as a music instructor. She was also, for three years, the organist at the Rialto Theatre in downtown Dayton. In 1925, she married Jack Kelty and moved to Louisville, where she raised seven children and served as a church organist. She died there in 1984.

In the Gennett studio, Ms. Dunlap provided solid accompaniment with a strong danceable ‘boom-chuck’ rhythm: a left hand bass note on the down beat, followed by an strong chord from the right hand on the upbeat. She used none of the flourishes or embellishments commonly displayed by other studio accompanists of that time. At the September 1924 session, J. M. Houchins accompanied Wm. B. Houchens on guitar on two masters with no piano, and with piano on the final master, a medley of Temperance Reel/ Reilly’s Reel. I can find no further information on a J. M. Houchins, but wonder if perhaps the Gennett studio ledgers might contain a spelling error or two. Was the guitarist possibly J. H. Houchens, the father of William, who lived with his son and daughter-in-law at three different Dayton addresses–they always rented, never owned–from 1921 through 1926. As mentioned earlier, James Henry died in Dayton in 1927.

Convention holds that William B. Houchens was not really a traditional fiddler, but a schooled violinist. And though I have found no record of any schooling beyond his mother teaching him to read music, there are traces of classical competence in his recorded performances. He did teach violin at both a Cincinnati conservatory and his own studio in a Dayton. Yet there are no grounds to assume that his fiddling was secondary to a classical repertoire, nor to suppose that his teaching did not call upon the reels, hornpipes and breakdowns of the Anglo-American fiddle tradition. Fiddle music had a substantial presence in music publishing from the 1840s on, and phonographic discs and cylinders of fiddle tunes appeared right at the dawn of the commercial recording industry. Violin playing and fiddling are not mutual exclusive categories; the middle is not excluded. William Bright Houchens was apparently both a violinist and a fiddler. The sonic evidence he left for us to enjoy is “well-fiddled.”

– Paul Tyler (aka DrDosido), February 25, 2024