Events of this past week have prompted me to renew my venture into the world of 18th and 19th Century musical manuscripts. My main interest is with notebooks compiled, used, and passed on by dance musicians from a time when country dances were highly popular and couple dances like the polka, waltz and mazurka were emerging as fashionable in city and country alike.

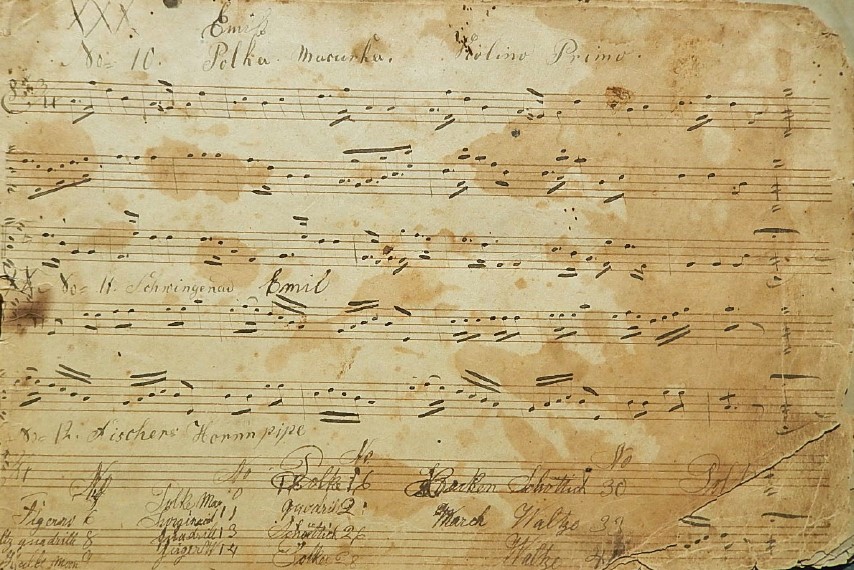

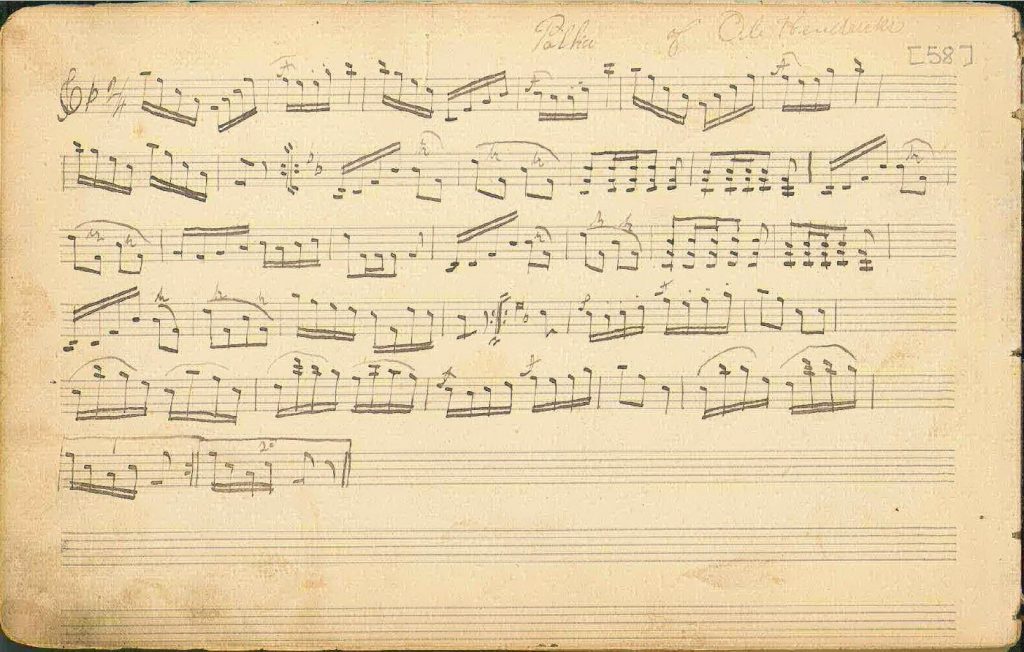

It was nearly thirty years ago that I got tangled up with a dozen of these old notebooks I found at the Indiana Historical Society, the Newberry Library, and in other institutions and private collections. Ruben M. Fisher’s Notebook, from Richland County, Ohio, 1844, was perhaps the most exciting discovery. (Page 5 is displayed to the left.) My initial scholarly inquiries into this area were then interrupted by other projects in the ensuing two decades.

A most serendipitous recent encounter has fired me up to study once again these treasures from our past. A Chicago friend, and former fiddle student of mine, Elizabeth Lamberti, took a job in Switzerland and met up with European musicians who are enthusiastic about old-time American fiddle music. At a recent workshop in Germany she played a few Midwestern tunes that caught the attention of Stefan Bussemas, a mandolinist with the band Wings on Strings (a performance with his previous band is at the end of this post). He was especially curious about the influence German immigrant musicians may have had on the American folk repertoire. Elizabeth put me in contact with Stefan.

Straight away I got an email from Stefan asking “about German roots in American folk-music.” It is an intriguing question that has been posed by a number of music scholars on this side of the pond, but there is no simple answer. Thirteen years ago on this blog, I made a small contribution to solving that puzzle: The Search for German Old-Time Music. I also referred him to the Indiana Fiddlers page of drdosido.net, and told him look for Hugh Sowers and for my name for tunes from Allen County in Northeastern Indiana; and then to scroll down to the entries for Joe Altman, Harold Haug, Herb Obermeyer, Herb Wenning, and Joe Witzberger for German tunes from Dubois County in Southern Indiana.

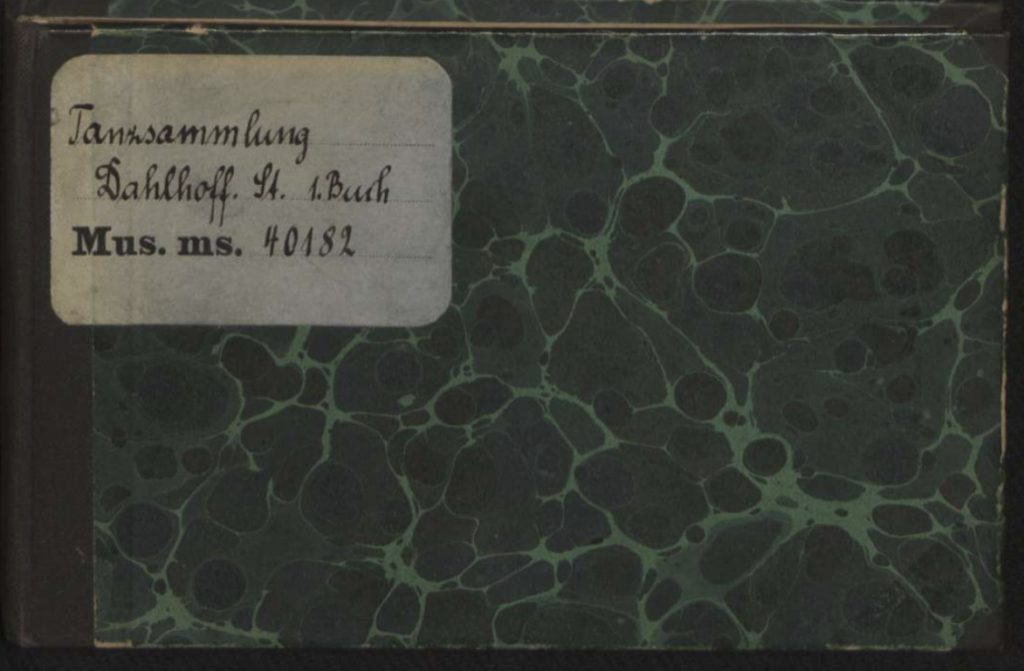

Stefan also had a wonderful present for me. In his own words: “I really like the tradition of folk-music played for dancers and there is a small but growing community digging out old handwritten collections of dance-music here in Northern Germany. While folk-music is more alive in Bavaria, the northern parts of Germany have only little memories of our own traditions. In the last ten years people were going into archives to find handwritten sheet-music. In the place where I was born and raised, North Rhine-Westphalia, this led to the finding of about 1400 pages of handwritten music, collected by a family of teachers and sextons, called the Dahlhoff-Sammlung.”

The sammlung (collection) comprises ten notebooks of social dance music written down between 1767 and 1799 in by the Dahlhoff Family, who were organists and sextons in the town of Dinker in the current state of Nordrhein-Westfalen. Stefan provided a link to a digitized copy of the notebooks accessible online at the Berlin State Library. In addition, he gave me a link to the late Richmud Rollenbeck’s website, which features her modern transcriptions of the entire set of the Dahlhoff Tanzsammlung.

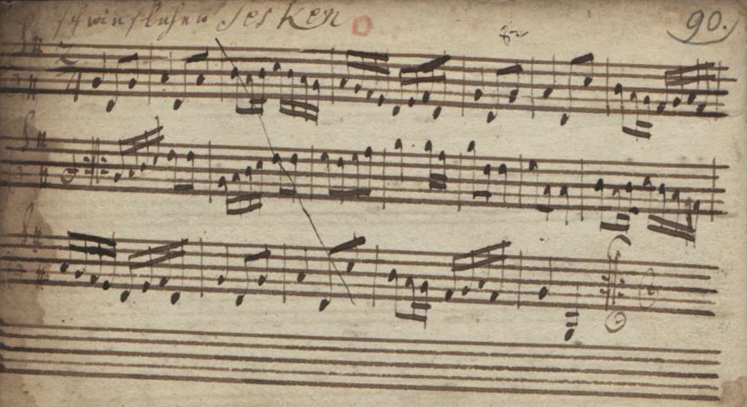

I dug in immediately and already have played through many of the tunes the Dahlhoffs wrote down two-and-a-half centuries ago. No immediate parallels with American old-time tunes have yet jumped out. But there are a lot of interesting melodies, with both familiar turns and surprising twists. They are clearly tunes for dancing. Minuets predominate. From my exposure to Finnish dance tunes, I happily learned that minuets were not simply a cultural possession of the elite, but were danced also by the common folk. Many other dance forms are also represented. Stefan shared his favorite.

And even though we’re not sure what a Sesken is–a sassy young woman or a dance form imported from England–we are already playing this tune in Chicago

Besides the musical treasures found herein, three things stand out from my new connection with this folk music tradition from Westphalia. 1) My ancestors came from there. My great-great-grandfather Johann Heinrich Franke migrated from the village of Quetzen, near Minden, to Allen County, Indiana in 1845 (I visited the old home place, Farm 21, in 1969). Quetzen is located on a small neck of North Rhein-Westphalia that extends into the neighboring state of Lower Saxony. The home towns of both Stefan and the Dahlhoff family are within 77 miles (124 kilometers) of my ancestral farm. 2) The Dahlhoff family was from Dinker, which is 12 miles away from the larger town of Soest, probably the namesake of a German community in Marion Township in Allen County. My Lutheran grade school basketball team was in the same conference with the team from Emmanuel Soest. And then we all ended up going to public high school together in Hoagland (see earlier blog post linked at the beginning of this essay).

And finally, 3) several of the Dahlhoff notebooks have a Latin inscription on their covers: “Amor Docet Musicam.” Richmud Rollenbeck translated this into German as “Die Liebe lehrt die Musik.” Google Translate renders it for me as “Love teaches music.” I would like to claim that motto as my own.

To reciprocate for the gifts I received from Stefan, my new German friend, I sent him a digital copy of August Mueller’s Notebook, a manuscript compiled in Ohio around 1850 or 1860. The notebook was mailed in 1926 to Henry Ford in Dearborn, Michigan by Christian Dickman, of New Bremen, Ohio, with the inscription “Old Music notes more than one hundred years old written by Professor August Mueller, Mecklenburg, Germany.” My old friend and fellow old-time music sleuth Paul Gifford found it while doing research at the Henry Ford archives, and sent me a PDF copy a few years ago. Paul’s genealogical digging found census references to August Mueller, a “professor of music,” in New Bremen. He perhaps died in 1897 in Auglaize County, Ohio. For the record, New Bremen, Ohio is about 55 miles from Hoagland, my home town.

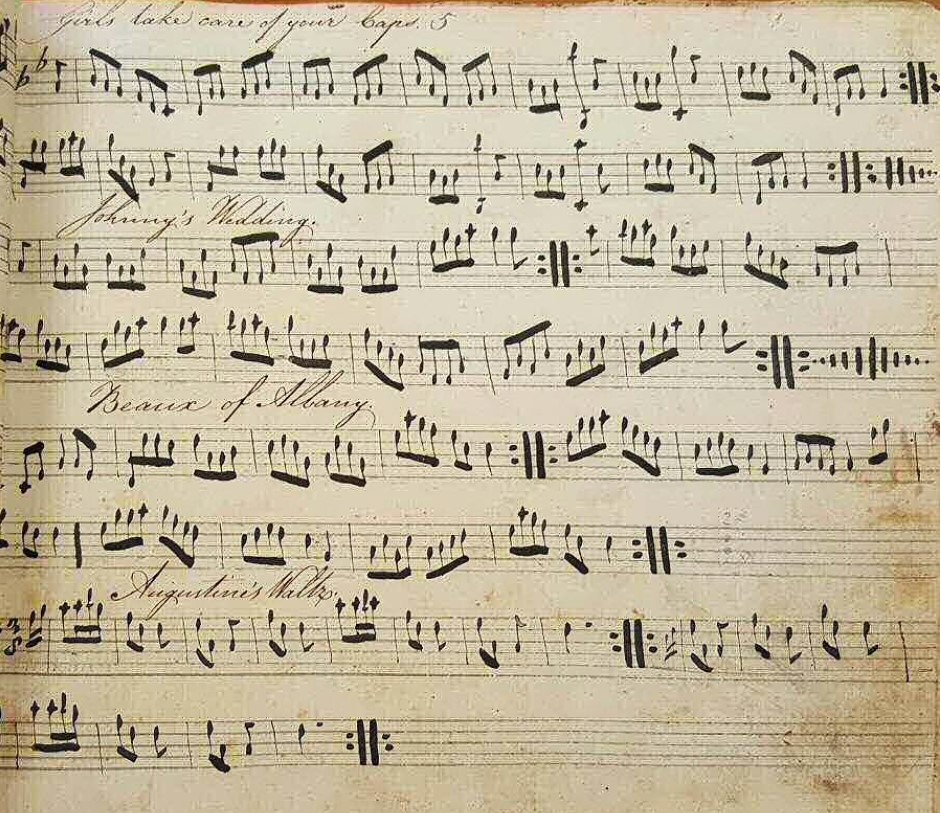

Also worthy of note is that New Bremen is about twice that distance, in the opposite direction, from Richland County, Ohio, where Ruben Fisher lived with his notebook (Page 5 is shown at the beginning of this post). Ruben Fisher was born in 1816 in Berks County, Pennsylvania in the heart of Pennsylvania Dutch country, and migrated to Ohio as a child (a snippet of a German newspaper still exists in the Fisher Notebook as a bookmark). However, besides the external German connections, there are few overt musical parallels between these two notebooks. The only clearly German folk dance tune in the Fisher Notebook is the Augustine Waltz, also known as Ach du Lieber Augustine, a piece played by all the musicians of German ethnicity that I encountered in Indiana. (By the way, that melody is often commonly used for the Scottish ditty “Did you ever see a Lassie.”)

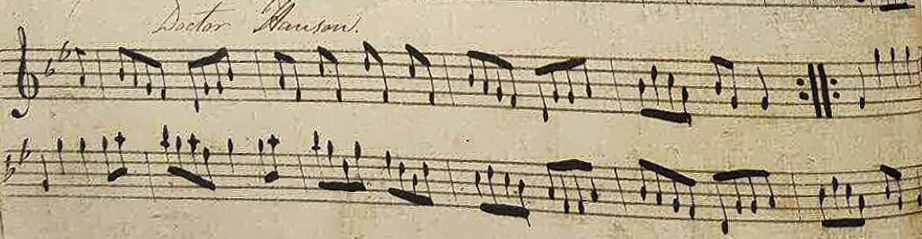

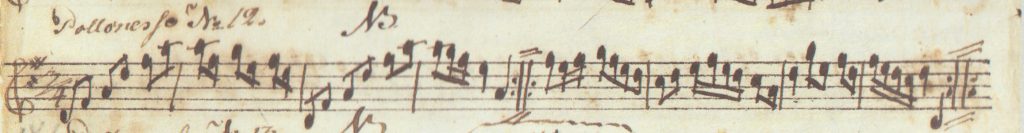

Compare sample pieces from these two notebooks. The preceding image, a page from the Mueller Notebook, begins with a Polka Mazurka, a dance tune of Central European provenance. The following piece, Doctor Hanson, from the Fisher Notebook, is a reel that has an Irish or Scottish character to it.

Still, I think connections exist between these manuscript collections because of the rich historical meaning each conveys. They are written representations of non-commercialized traditions of dancing and music-making from parallel communities of common folk. Both notebooks, as well as the Dahlhoff Sammlung, are stunning windows into the artistic and social life of communities and peoples that have too often been overlooked by historians and cultural commentators. All these manuscripts, and the social historical contexts in which they were compiled and preserved, are worthy of further study and reflection.

And there is more.

The same week that I met Stefan Bussemas and the Dahlhoff Sammlung, I was asked to teach a tune for our monthly ScandiJam at the Swedish-American Museum on Chicago’s north side. I chose a tune that was played for me by Patrik Weckman on my first visit to Finland in 2009. This recording (2nd audio clip below) was made at a private jam session in the back room of the Old Anchor Inn in Helsinki. Patrik identified it only as a polonaise, and described it as an archaic type of tune. After I mastered playing the tune, I messaged Patrik and asked where he had learned it. I suggested that it resembled Pollonessa #12 in Adolf Fredrick Stare’s Notebook compiled on Finland’s west coast in 1806. A mutual friend of ours, Arto Järvelä had given me a published facsimile of Stare’s notebook.

Patrik got back to me almost immediately and reported that this was Pollonesse # 7 in the Nyberg Collection. This was a source that I had never heard of. Patrik wrote: “Carl Peter Nyberg (1766-1847) . . . left about a dozen note books. King of Sweden gave him title War councelor! He was the last cashier in Viapori or Suomenlinna* in late 18th and early 19th century.” (* An island fortress in Helsinki Harbor)

And one more link in the chain.

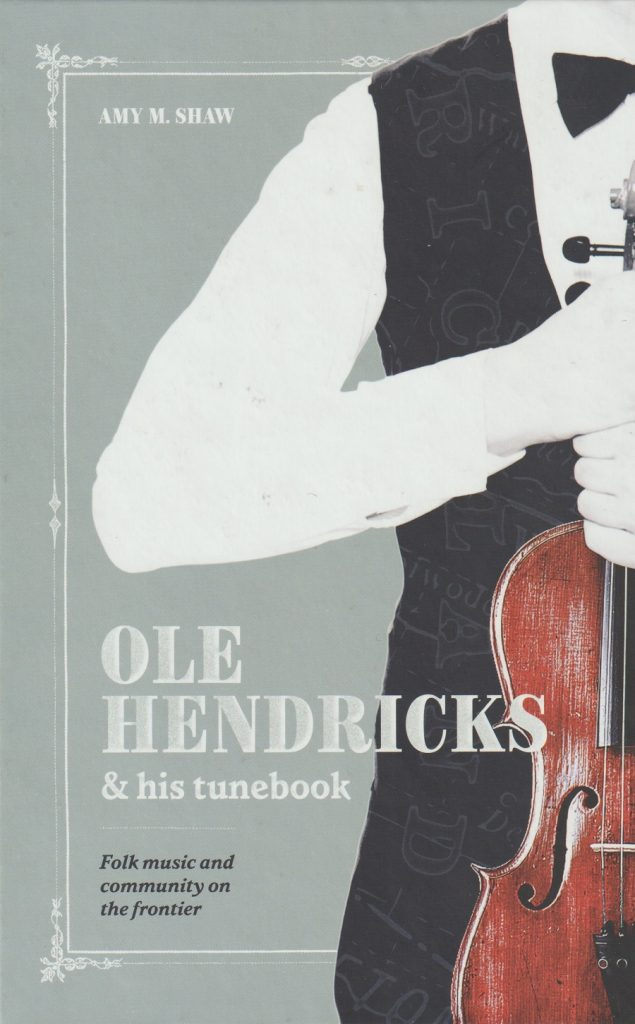

Upon establishing contact with Stefan in Germany, I renewed a long-running conversation with Paul Gifford about fiddle tune history. I told him I had sent a digital copy of the August Mueller Notebook to my new friend in Germany, and shared with him the links I had been given for German tunes. In the course of that conversation, I asked Paul if he had seen the book Ole Hendriks and His Notebook: Folk Music and Community on the Frontier, published in 2020 by the University of Wisconsin Press. (Disclaimer: I was an editorial reader for that manuscript.) A companion CD, Play It Again, Ole! has also been issued. Paul appreciated the recommendation.

Olaf Andrew Hendricks (1851-1935) was a fiddler and dance musician from Norway who, when he was three-years-old, migrated with his family to Wisconsin. He spent his adult years keeping a tavern and playing for public dances in several towns in North Dakota and Minnesota in the late 1800s. His manuscript collection of tunes had come into the possession of Beth Rotto of Decorah, Iowa. Beth and I have mutual friends, and my daughter Maddy had played music with Beth when she was in college in Decorah. I knew of this notebook, and was very glad to see Amy Shaw’s monograph presenting and analyzing the life and music of Ole Hendricks. This is one of very few published works in the United States that gives attention to even the presence, let alone the importance, of these handwritten notebooks full of folk dance tunes.

In future posts I will have more to say about the manuscript notebooks I have had a chance to look at and play through. One thing that is readily apparent in each is the labor and love that went into inscribing in permanent form the music that surged through the hands, heads, and hearts of these musicians. I am continually astonished by how traditional music connects us to so many distant times and places, and to so many different people.

I just love this stuff.

— Paul Tyler, PhD (DrDosido), January 28, 2024