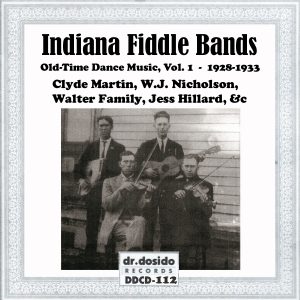

Though I am a few days late, I would like to kick off this planned series of posts with an item that honors my native state of Indiana. In 2016, Hoosiers celebrated 200 years of statehood. My commemorative gift to my home state is an album of old-time fiddling recorded by musicians from Indiana, all of it recorded in Indiana between 1928 and 1933. With this, I begin a series that is the fruit of my long love affair with old-time music as recorded during the era of 78rpm phonograph discs. For a number of writing projects over the last 15 years, I have been compiling and editing sounds and data from that period into playlists that shed some light on Midwestern contributions to American folk and vernacular music. With this offering, I turn my studious playlists into virtual CDs for all to share.

Of the 24 sides included in this first posted album, 13 have never been commercially reissued on LP, cassette tape, or CD. And about half of those that have been reissued for modern consumption can be found only on non-American labels. The portion of the music business in the United States that is interested in old-time rural music has largely ignored the Midwest. I like to think of this series as centered on what Frank Fairfield calls “The Outsiders of Old-Time Music.” I will explain more in future posts.

Meanwhile, enjoy listening. I have written up introductory sketches of these outsider artists. And I have compiled basic discographic information in a file that can be accessed and downloaded in the link that follows. (The conventions and forms of my discographic entries are shown in the DrDosido CDs page linked in the menu bar above. A list of instrument abbreviations can also be found there.)

112 Indiana Fiddle Bands I (discography, plus album cover).

In a not-yet published article, country music historian Pat Huber described Floyd Thompson & His Home Towners as an Indianapolis-based studio band of “trained, sight-reading professional musicians” who, with the addition of transplanted Kentuckian Emry Arthur, presented “a colorful blending of Midwestern urban jazz and popular music and Southern rural vernacular traditions.” What is implied here is a strict separation between not only Midwestern and Southern musical styles, but also between trained musicians and folk musicians, as well as between urban and rural sensibilities. I am not convinced that musical experience can be so neatly compartmentalized. And then, after agreeing with Tony Russell’s assessment that the Home Towners, were inspired by the “Broadway hillbilly music of Carson Robison and Frank Luther,” Huber further claims that it is Arthur that gives the Home Towners genuine old-time credibility (Russell, 2007, p. 97; Huber, np).

Where to start? Russell is correct in suggesting that Floyd Thompson was probably inspired by the commercial success of Robison and Luther, leading him to bring together the Home Towners, an ephemeral and changing assemblage of violinists, vocalists, guitar pickers, and harmonica blowers, in order to make recordings of old-time music. However, it is not fair or accurate to reduce the band’s music to an act of copycatting. The Home Towners were clearly comfortable with a variety of vernacular material, plus they brought with them a number of Thompson’s original compositions (several will be heard on another offering in this series). While fans of old-time music might respond differently to the various sounds that constitute the genre, individual aesthetic preferences do not provide a sound definitional basis.

Huber, also, is on the right track in describing the music of the Home Towners as a colorful blend. But he is mistaken in suggesting that the different strands of that blend can be ascribed to the regional provenance of individual members of the group. In other words, what differentiates the music of the Home Towners from other contemporary popular styles was not the mere presence of Emry Arthur. “Trained, sight-reading, professional musicians” are not necessarily divorced from the vernacular music of their communities. In my generation, most trained professional musicians know rock and roll, rhythm and blues, and the American songbook. In the 1920s, it would have been natural for such musicians to be familiar with string band music, social dance music, and square dance tunes. Yes, even in Indiana and the whole of the Midwest.

Floyd Thompson & His Home Towners

1928

1. Little Brown Jug

2. Ida Red

3. Rye Waltz

There is no doubt about the old-time authenticity of the next band up–James Cole’s String Band, also known as James Cole’s Washboard Band–though these musicians also faced catagorical challenges. The record companies of the day expected blues from the African-American artists they recorded for their “Race” series. But James Cole and his associates, including Tommy Bradley, were equally at home with styles and repertoire more commonly associated with Anglo-American musicians: square dance tunes and songs from Tin Pan Alley. For a long while, not much was know about the backgrounds of Cole or Bradley. Discographer Dick Spottswood suggested“they may be from central/western Kentucky, where, even by the 1920s, black and white string band styles and repertoire were still quite close” (Spottswood). And perhaps that is where they came from, but Tony Russell has recently asserted that they worked out of Indianapolis, while also teaming up with compatriots in Cincinnati.

The instrumental pieces recorded by Cole and Bradley defy categorization. Bill Cheatem, of course, is an old chestnut in Anglo-American fiddle traditions. But could the tune possibly be named for African-American showman William Cheathem, who along with his brother Lawrence, founded the Cheathem Brothers’ Black Diamond Minstrels in St. Louis, Missouri in 1898? (Abbott & Seroff, p. 92). According to record producer Marshall Wyatt, Runnin’ Wild is from a 1922 pop song composed by A. Harrington Gibbs (Wyatt, p. 25). Sweet Lizzie has not been traced, but it closely resembles Sweet Sue, Just You, a hit song introduced in 1928 in Chicago, where the song’s composer, Victor Young, had been a member of Ben Pollack’s band, who recorded the latter song in April of that year.

James Cole’s String Band

1928

4. Bill Cheatem

5. I Got a Gal

James Cole’s Washboard Band

1930

6. Runnin’ Wild

7. Sweet Lizzie

Nicholson’s Players

1928

8. Irish Washerwoman Medley

9. Turkey in the Straw Medley

10. Muskakaktuck Waltz

11. My Honey

Were it not for the prodigious research of the late, great Gus Meade, we would know nothing at all about the musicians who made up the Hoosier Rangers. Clyde Martin & the Hoosier Rangers recorded 4 selections at the Gennett studios in Richmond in 1931. According to Meade’s Fiddlers Compendium, the band’s leader, Clyde Martin, played piano. The rest of the Rangers were all named Wright. Cecil Wright, the lead fiddler, was born in 1904 in Washington County, Indiana, and was of the same generation as the younger members of Nicholson’s Players, i.e., Ashabraner and Spurgeon. Perhaps musical connections were made. (Cecil, by the way, spent his later years up north in LaFountain, a town with Tyler family connections.) The other Wrights, likely brothers or cousins, were Elmo Wright on guitar and Howard Wright, who, according to Meade, played the banjo. However, banjo is not audible on either selection included here. Meade asks whether Howard played the mandolin that can be heard on Little Brown Jug/ White River Bottoms. I would further ask if it was Howard Wright who played the droning 2nd fiddle on Shuber’s Hoedown.

A bit of a side note illustrates the magnitude of Gus Meade’s discographical and historical accomplishments. As he died in 1991, all his research was done with little help from the nascent internet or the World Wide Web. A quarter-century later, an hour’s worth of research in an online newspaper archive disclosed that Clyde Martin, leader of the Hoosier Rangers was something of a celebrity in the mid-1920s. Born around 1886, Martin was a college graduate, basketball star, and a community leader in Palmyra, Indiana, where he built Ranger Hall to provide recreation for the community after the local school board voted against adding a gymnasium to the school. Ranger Hall was well-used by the community for basketball games, roller skating, amateur dramatics, checker-playing, and a slot machine for games of chance. These activities were a threat to the local Church of Christ–they approved of basketball, but not of roller skating–and in a 1926 trial that received nation-wide attention, church officials charged Martin with heresy and excommunicated him for being “too worldly.” Undeterred, Martin announced that he would keep Ranger Hall open and would become a Republican candidate for Congress. His candidacy did not succeed. In the summer of 1929, he turned in part to music, as the Steedman Symphonic Society of Louisville sponsored a series of summer concerts that included the “Hoosier Ranger and His Gang, direction, W. Clyde Martin, Palmyra, Ind.” (Courier-Journal: August 25, 1929). Two years later, he took his gang north to the Gennett studios in Richmond.

Back to the music: the second piece in the aforementioned medley, White River Bottoms, is of special interest. Gus Meade notes in Country Music Sources that the tune was played by Jimmy Campbell of Dolan, Indiana in 1956. I listened to Meade’s field recordings of Campbell, as held in the Archives of Traditional Music at Indiana University, and met Jimmy Campbell in 1980, a few years before his passing. Inspired by Meade’s field work, I undertook my own search for White River Bottoms and the like, and collected it from a handful of Hoosier fiddlers, ranging from Frank Wisehart’s home recording in the 1940s to frequent performances by both Cyprien and Lotus Dickey in the 1980s. One Crawford County fiddler who moved north to Indianapolis, Noble Melton, described the tune as a glorified version of Boil Them Cabbage Down. I have played the tune often over the years. After one performance, musician, historian, and 78 collector Kinney Rorrer told me about the Hoosier Rangers 78 and later sent me a taped dub. I am extremely grateful to Kinney and all the friends and acquaintances who have generously shared a rich wealth of old-time music from the fascinating era of the 78rpm phonograph disc.

Clyde Martin & the Hoosier Rangers

1931

12. Little Brown Jug/ White River Bottoms

13. Shuber’s Hoe Down

While Nicholson’s Players, and perhaps the Wright brothers. were all from Hoosier families, the next band up, Richard Cox & His National Fiddlers was new to Indiana. Richard Cox (b. 1915) was from Huntington, West Virginia, where he began his radio career as a teen in 1929 on WSAX, and was soon dubbed West Virginia’s Master Mountaineer, despite his youth. After leading bands in the three-state area around Huntington (Ohio, West Virginia, and Kentucky), in 1932 Cox took a band west along the National Road (US 40) and landed in Richmond, Indiana, where they recorded nine pieces–blues, songs, and fiddle tunes–two of which are heard here. Over the next few years he appeared on several Midwestern radio stations (Detroit, Windsor, and Gary). By 1936, according to historian Ivan Tribe, Cox “joined forces with two old pros from the deep South, Bert Layne and Riley Puckett, and an Ashland [KY] youth, Slim Clere, as part of a group called the Mountaineer Fiddlers. This band played radio shows and personal appearances in the Gary, Indiana/Chicago area” (Tribe, p. 40).

Besides Richard Cox, the National Fiddlers, included fiddler Bernard Henson and guitarist, Frank Welling, who recorded extensively for Gennett between 1927 and 1933. One might surmise that the elder Welling (b. 1900), also a resident of Huntington and veteran performer on WSAZ, arranged this trip to the recording studio in Indiana for the younger musicians. Russell’s discography credits the fiddle and guitar to either Cox or Henson, but gives no acknowledgment to the steel guitar heard prominently on these performances. It is likely that Frank Welling played the Hawaiian steel, which he learned in 1919 while working with Domingo’s Filipino Serenaders, a vaudeville act (Tribe, p. 29). One of the tunes recorded by Cox, Henson, and Welling, The Downfall of Adam, is related to Mississippi Sawyer, a standard American fiddle tune that is derived from the British/European Downfall of Paris.

Richard Cox & His National Fiddlers

1932

14. East Tennessee Blues

15. The Downfall of Adam

In Richmond, the Walter Family merged with other local musical families. Daughter Betty Lou, who sang “old ballads” as the “Singing Schoolmarm” on WKBV, married local banjoist and broadcaster Ray Agee, who helped the radio station relocate from Brookville to Richmond. Later on, according to Richmond Palladium-Item columnist Dick Reynolds, “Ray Agee organized the ‘Home Folks Show,’ a stage show whose members included the Agees’ two sons, Highly and Chuck.” The Agees later operated a music store in Richmond. In her senior years, Betty Lou Walter Agee was still playing jaw harp with a local senior citizen band, Charlie Estes & Company (Reynolds, p. 5). Possibly this was the same Charlie Estes who played guitar with the Walter Family at the recording session in 1933.

Walter Family

1933

16. Flying Cloud Waltz

17. Walter Family Waltz

18. That’s My Rabbit, My Dog Caught It

19. Shaker Ben

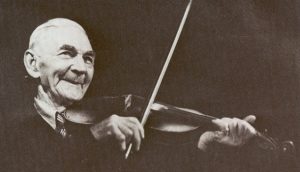

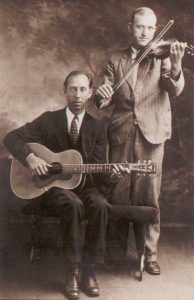

The last band on this album features the fiddling of another West Virginian, Jess Johnston (1898-1952) from Wyoming County. From 1930 through 1933, Johnston was a regular visitor to the Gennett studios in Richmond, Indiana, where he participated in at least nine sessions with a variety of old-time artists, starting with Byrd Moore from Virginia. Here is a list of Johnston’s studio work.

September-October 1930, w/ Byrd Moore

December 1930, w/ Roy Harvey

June 1931, w/ Ernest Branch & Bernice Coleman (West Virginia Ramblers)

June 1931, w/ Roy Harvey (West Virginia Ramblers)

September 1931, poss, w/ Jess Hillard

October 1931, w/ Duke Clark

October 1931, w/ Ted Lunsford

November 1931, own session, with Bert Froste

February & July 1933, with Jess Hillard His West Virginia Hillbillies

Three of the musicians on this list–Harvey, Branch,and Coleman–are fellow West Virginians. And like Byrd Moore, Roy Harvey was a prominent old-time recording artist. During his multiple visits–or extended stay–in Richmond, Jess Johnston did well in an Old Fiddlers Contest held at the local high school in October 1931. He took first place in fiddle, comic song, blue [sic] singing, piano solo, and Arkansas Traveler.

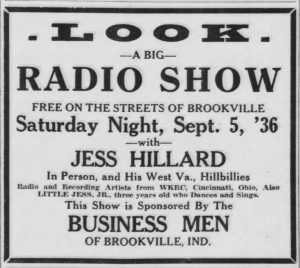

At the end of the above list is a Hoosier, Jess Hillard, who also made a respectable showing at the Old Fiddlers Contest, with second place in Comic song and third place in Duet song. (I am not sure if there is any connection between Jess Hillard the guitarist and Jess S. Hillard of Boston, Indiana, who was wanted for passing bad checks in 1920; or with Jess C. Hillard of Richmond, who injured his hand in a gun accident in 1949). Born in 1895, Jess Hillard the guitarist had many connections to Richmond. Harry Hillard, likely Jess’ brother, and Duke Clark, an occasional musical partner, also appeared at the same fiddlers contest and other events in the area. All three, in various combinations, made recordings at Gennett, with Jess being the most prolific: 42 sides recorded at 14 sessions between April 1931 and July 1933.

At the last of those sessions, Hillard was rejoined by Jess Johnston for 7 fiddle tunes and 2 songs, all released as by Jess Hillard & His West Virginia Hillbillies. Five of those tunes are included here. All of them have evocative names and familiar strains that hearken to other well known tunes. Rolling River is clearly related to the Dubuque family of tunes. Hell Up Flat Creek recalls Cricket on the Hearth. Make Down the Bed and We’ll All Sleep Together is an interesting twist on Rocky Mountain Goat.

1933 was a good year for Jess Hillard and Jess Johnston. In April, the West Virginia Hillbillies took top prize for the second straight year at an old-time band and fiddle contest sponsored by the National Fiddlers Association of Indianapolis. Besides Johnston on fiddle, Jess Hillard’s lineup that night included Duke Clark on guitar, Clarence Johnson on tenor guitar, and Nelson Hillard (another brother?) on guitar. Jess Hillard continued to be active in the area through at least 1936 with a billing that regularly noted he was a radio star on WKRC in Cincinnati. It is likely that Jess Johnston was still part of that group of West Virginia Hillibillies.

Jess Hillard & Jess Johnston

1933

20. Make Down the Bed and We’ll All Sleep Together

21. Rolling River

22. Dixie Rag

23. Wild Goose Waltz

24. Hell Up Flat Rock

– Paul Tyler, PhD (aka DrDosido)

January 6, 2017

References Cited

Abbott, Lynn & Doug Seroff. 2002. Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895. University Press of Mississippi.

Huber, Patrick. 2013. Floyd Thompson and His Home Towners. Unpublished paper.

Meade, Guthrie T. N.d. The Fiddler’s Compendium. Typescript.

Meade, Guthrie T. Jr. with Dick Spottswood & Douglas S. Meade. 2002. Country Music Sources: A Biblio-Discography of Commercially Recorded Traditional Music. Southern Folklife Collection.

Richard Nevins, Liner Notes to Old Time Fiddle Band Music from Kentucky, Vol. 3: Way Down South in Dixie. Morning Star Records 45005, 1980.

Reynolds, Dick. 1982. 82-Year-Old Twanger Earns Ovations. Richmond Palladium-Item (March 1): 5.

Russell, Tony. 2004. Country Music Records: A Discography, 1921-1942. Oxford University Press.

Russell, Tony. 2007. Country Music Originals: The Legends and the Lost. Oxford University Press.

Russell, Tony. 2013. Nicholson’s Players. The Old-Time Herald 13 no. 5: 28-35

Spottswood, Dick. 2005. Liner notes to Tommy Bradley-James Cole Groups, 1928-1932. Document CD-5189.

Tribe, Ivan M. 1984. Mountaineer Jamboree: Country Music in West Virginia. University Press of Kentucky.

Wyatt, Marshall. 2002. Liner notes to Down in the Basement: Joe Bussard’s Treasure Trove of Vintage 78s. Old Hat CD-1004, 2002.

Jess[e] Hillard (actually b. 1895) was living in Boston, IN, in 1920 so was presumably the bad-check guy. Harry Hillard was definitely Jess[e]’s brother; Nelson Hillard was Jess[e]’s son. The Indianapolis provenance of the James Cole band is supported by multiple Indpls listings for a possible Tommie Bradley and for mandolinist Eddie Dimmitt. Jess Johnston’s dates are 1898-1952; he was the subject of an article by Kinney Rorrer and myself in Old Time Music 37 (Autumn 1981–Spring 1982).

Thanks, Tony. I will make the corrections. I took my dates for Jess Johnston from Gus Meade. I’ll look for your article in OTM 37. I calculated Jess Hillard’s birth year from the 1949 newspaper article about Jess C. Hillard, age 55, who shot his hand. He might be one and the same with bad check Jess S. Hillard. Not sure that small town newspaper reporters always fact-checked middle initials.

Jess[e] Hillard’s middle name was Smith, so I’d be fairly confident he was the bad-check Jess S. Hillard from Boston, IN. He was a Richmond resident in 1949 so I agree he may well be the Jess C. [sic] Hillard of the shooting incident.

Further to the bad-check affair: Jesse Hillard of Wayne County was sentenced to 1-5 years in the Indiana Reformatory for “issuing [a] fraudulent check” on 3-31-21, and on 5-27-31 he petitioned for a hearing before the state board of pardons (Kokomo Tribune, 5-27-21). I have not ascertained whether his petition was successful.

Yes

What a lot of effort! One formatting suggestion: remove the type on the edge of the Moore and Johnston picture and move it underneath the picture.

How do I order a CD?

This is it. It’s virtual. I’m not selling anything.

Congratulations Paul! This is a great job of preserving music and history of times long ago. It’s a treasure of hard work. My sincere thanks.

Thank you Paul!

I appreciate your hard work & diligence to get these wonderful important works of art out to the public.

Stew

Nice Job. Is there enough for a Volume 2? Or is that Illinois and Chicago radio people?

I guess “North of the Ohio” looks finished.

Paul,

This is really great, thank you for putting it together. Draper Walter was my great-great- grandfather. I can remember Betty Lou (my Granny) playing the jaw harp when I was young although that memory is pretty fuzzy. My father worked in their music store in Richmond and is a musician in Nashville and still records using the same banjo Ray Agee (his grandfather) played on those recordings.

Thanks again for compiling these all together.

We ran across your site while searching for a fiddler for an event in October this year, 2019. Do you happen to know of a fiddler able to play a 2 hour dance – square and otherwise in the Indianapolis area?

We’ll appreciate any leads you might have. We lost ours and time is growing short – not sure how to research this!

Best wishes for your labor of love on this website!!!

The Childs

My dad was an amazing fiddler with the Mudslingers. This square dance band played for many decades in Hoagland and the Fort Wayne area. If you want any history or recording of their band, I have many. My brother still lives in Adams County by St. Peters. If you want to know more, let me know. Always glad to celebrate memories!